Radioactive decay

It became clear from these experiments that there was a form of invisible radiation that could pass through paper and was causing the plate to react as if exposed to light.

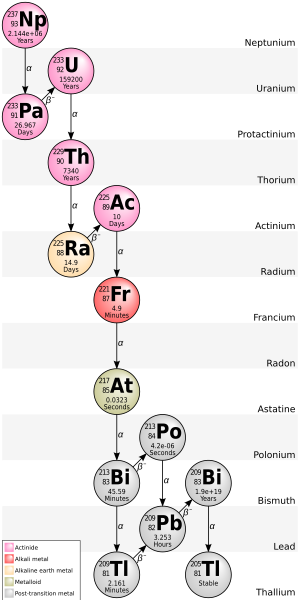

Subsequently, the radioactive displacement law of Fajans and Soddy was formulated to describe the products of alpha and beta decay.

A systematic search for the total radioactivity in uranium ores also guided Pierre and Marie Curie to isolate two new elements: polonium and radium.

After their research on Becquerel's rays led them to the discovery of both radium and polonium, they coined the term "radioactivity"[13] to define the emission of ionizing radiation by some heavy elements.

He also stressed that "animals vary in susceptibility to the external action of X-light" and warned that these differences be considered when patients were treated by means of X-rays.

By the 1930s, after a number of cases of bone necrosis and death of radium treatment enthusiasts, radium-containing medicinal products had been largely removed from the market (radioactive quackery).

In 1927, Hermann Joseph Muller published research showing genetic effects and, in 1946, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his findings.

The second ICR was held in Stockholm in 1928 and proposed the adoption of the röntgen unit, and the International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC) was formed.

After World War II, the increased range and quantity of radioactive substances being handled as a result of military and civil nuclear programs led to large groups of occupational workers and the public being potentially exposed to harmful levels of ionising radiation.

Bismuth-209, however, is only very slightly radioactive, with a half-life greater than the age of the universe; radioisotopes with extremely long half-lives are considered effectively stable for practical purposes.

In a phenomenon called cluster decay, specific combinations of neutrons and protons other than alpha particles (helium nuclei) were found to be spontaneously emitted from atoms.

These lightest stable nuclides (including deuterium) survive to today, but any radioactive isotopes of the light elements produced in the Big Bang (such as tritium) have long since decayed.

Thus, all radioactive nuclei are, therefore, relatively young with respect to the birth of the universe, having formed later in various other types of nucleosynthesis in stars (in particular, supernovae), and also during ongoing interactions between stable isotopes and energetic particles.

For example, carbon-14, a radioactive nuclide with a half-life of only 5700(30) years,[27] is constantly produced in Earth's upper atmosphere due to interactions between cosmic rays and nitrogen.

Radioactive decay has been put to use in the technique of radioisotopic labeling, which is used to track the passage of a chemical substance through a complex system (such as a living organism).

For geological materials, the radioisotopes and some of their decay products become trapped when a rock solidifies, and can then later be used (subject to many well-known qualifications) to estimate the date of the solidification.

Thereafter, the amount of carbon-14 in organic matter decreases according to decay processes that may also be independently cross-checked by other means (such as checking the carbon-14 in individual tree rings, for example).

This kinetic energy, by Newton's third law, pushes back on the decaying atom, which causes it to move with enough speed to break a chemical bond.

[32] Radioactive primordial nuclides found in the Earth are residues from ancient supernova explosions that occurred before the formation of the Solar System.

While the underlying process of radioactive decay is subatomic, historically and in most practical cases it is encountered in bulk materials with very large numbers of atoms.

The decay rate, or activity, of a radioactive substance is characterized by the following time-independent parameters: Although these are constants, they are associated with the statistical behavior of populations of atoms.

The mathematics of radioactive decay depend on a key assumption that a nucleus of a radionuclide has no "memory" or way of translating its history into its present behavior.

Aggregate processes, like the radioactive decay of a lump of atoms, for which the single-event probability of realization is very small but in which the number of time-slices is so large that there is nevertheless a reasonable rate of events, are modelled by the Poisson distribution, which is discrete.

[33] The mathematics of Poisson processes reduce to the law of exponential decay, which describes the statistical behaviour of a large number of nuclei, rather than one individual nucleus.

[44] A number of experiments have found that decay rates of other modes of artificial and naturally occurring radioisotopes are, to a high degree of precision, unaffected by external conditions such as temperature, pressure, the chemical environment, and electric, magnetic, or gravitational fields.

[citation needed] Recent results suggest the possibility that decay rates might have a weak dependence on environmental factors.

[46][47][48] However, such measurements are highly susceptible to systematic errors, and a subsequent paper[49] has found no evidence for such correlations in seven other isotopes (22Na, 44Ti, 108Ag, 121Sn, 133Ba, 241Am, 238Pu), and sets upper limits on the size of any such effects.

[51] An unexpected series of experimental results for the rate of decay of heavy highly charged radioactive ions circulating in a storage ring has provoked theoretical activity in an effort to find a convincing explanation.

[55] The most common and consequently historically the most important forms of natural radioactive decay involve the emission of alpha-particles, beta-particles, and gamma rays.

The process represents a competition between the electromagnetic repulsion between the protons in the nucleus and attractive nuclear force, a residual of the strong interaction.