Nuclear emulsion

It is compact, with no associated read-out cables or electronics, allowing the plates to be installed in very confined spaces and, compared to other detector technologies, is significantly less expensive to manufacture, operate and maintain.

[1] The chief disadvantage of nuclear emulsion is that it is a dense and complex material (silver, bromine, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen) which potentially impedes the flight of particles to other detector components through multiple scattering and ionising energy loss.

[10] In 1905 he was using commercially available photographic plates to continue his research into the properties of the recently discovered alpha rays produced in the radioactive decay of some atomic nuclei.

He completed this research project in 1909,[12] showing that it was possible “by preparing an emulsion film of very fine silver halide grains, and by using a microscope of high magnification, that the photographic method can be applied for counting 𝛂-particles with considerable accuracy”.

In particular Marietta Blau, working at the Institute for Radium Research, Vienna in Austria, began in 1923 to investigate alternative types of photographic emulsion plates for detection of protons, known as “H-rays” at that time.She used a radioactive source of 𝛂-particles to irradiate paraffin wax, which has a high content of hydrogen.

But the onset of political unrest in Austria and Germany, leading to World War II, brought a sudden halt to progress in that field of research for Marietta Blau.

[21][22] In 1938, the German physicist Walter Heitler, who had escaped Germany as a scientific refugee to live and work in England, was at Bristol University researching a number of theoretical topics, including the formation of cosmic ray showers.

This intrigued Powell, who convinced Heitler to travel to Switzerland with a batch of llford half-tone emulsions[24] and expose them on the Jungfraujoch at 3,500 m. In a letter to 'Nature' in August 1939, they were able to confirm the observations of Blau and Wambacher.

Distance and circumstances denied Bose and Chowdhuri the relatively easy access to manufacturers of photographic plates available to Blau and later, to Heitler, Powell et al..

First, in 1947, Cecil Powell, César Lattes, Giuseppe Occhialini and Hugh Muirhead (University of Bristol), using plates exposed to cosmic rays at the Pic du Midi Observatory in the Pyrenees and scanned by Irene Roberts and Marietta Kurz, discovered the charged Pi-meson.

[6] Then known as the ‘Tau meson’ in the Tau-theta puzzle, precise measurement of these K-meson decay modes led to the introduction of the quantum concept of Strangeness and to the discovery of Parity violation in the weak interaction.

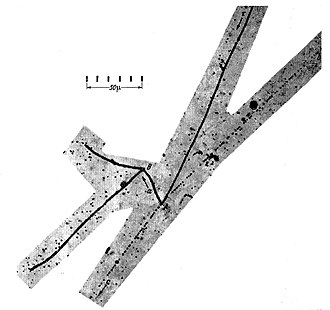

Rosemary Brown called the striking four-track emulsion image,[1] of one 'Tau' decaying to three charged pions, her "K track", thus effectively naming the newly discovered ‘strange’ K-meson.

[41] There exist a number of scientific and technical fields where the ability of nuclear emulsion to accurately record the position, direction and energy of electrically charged particles, or to integrate their effect, has found application.

π −

meson ( a ) and two

π +

mesons ( b and c ). The

π −

meson interacts with a nucleus in the emulsion at B .