Nucleic acid secondary structure

In molecular biology, two nucleotides on opposite complementary DNA or RNA strands that are connected via hydrogen bonds are called a base pair (often abbreviated bp).

Some DNA- or RNA-binding enzymes can recognize specific base pairing patterns that identify particular regulatory regions of genes.

[2] The larger nucleobases, adenine and guanine, are members of a class of doubly ringed chemical structures called purines; the smaller nucleobases, cytosine and thymine (and uracil), are members of a class of singly ringed chemical structures called pyrimidines.

[4] These mechanical features are reflected by the use of sequences such as TATAA at the start of many genes to assist RNA polymerase in melting the DNA for transcription.

The cell avoids this problem by allowing its DNA-melting enzymes (helicases) to work concurrently with topoisomerases, which can chemically cleave the phosphate backbone of one of the strands so that it can swivel around the other.

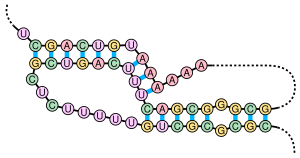

Frequently these elements, or combinations of them, are further classified into additional categories including, for example, tetraloops, pseudoknots, and stem-loops.

Topological approaches can be used to categorize and compare complex structures that arise from combining these elements in various arrangements.

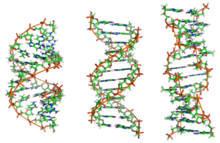

The nucleic acid double helix is a spiral polymer, usually right-handed, containing two nucleotide strands which base pair together.

There are many secondary structure elements of functional importance to biological RNAs; some famous examples are the Rho-independent terminator stem-loops and the tRNA cloverleaf.

This makes the presence of general pseudoknots in nucleic acid sequences impossible to predict by the standard method of dynamic programming, which uses a recursive scoring system to identify paired stems and consequently cannot detect non-nested base pairs with common algorithms.

Most methods for nucleic acid secondary structure prediction rely on a nearest neighbor thermodynamic model.

[14] Dynamic programming algorithms often forbid pseudoknots, or other cases in which base pairs are not fully nested, as considering these structures becomes computationally very expensive for even small nucleic acid molecules.

For example, microRNAs have canonical long stem-loop structures interrupted by small internal loops.