Nucleosome

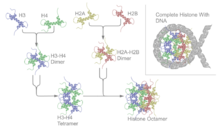

The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone proteins[1] and resembles thread wrapped around a spool.

[2] In addition to nucleosome wrapping, eukaryotic chromatin is further compacted by being folded into a series of more complex structures, eventually forming a chromosome.

[4] Nucleosomes were first observed as particles in the electron microscope by Don and Ada Olins in 1974,[5] and their existence and structure (as histone octamers surrounded by approximately 200 base pairs of DNA) were proposed by Roger Kornberg.

[17] Histone equivalents and a simplified chromatin structure have also been found in Archaea,[18] suggesting that eukaryotes are not the only organisms that use nucleosomes.

Pioneering structural studies in the 1980s by Aaron Klug's group provided the first evidence that an octamer of histone proteins wraps DNA around itself in about 1.7 turns of a left-handed superhelix.

[19] In 1997 the first near atomic resolution crystal structure of the nucleosome was solved by the Richmond group, showing the most important details of the particle.

The human alpha satellite palindromic DNA critical to achieving the 1997 nucleosome crystal structure was developed by the Bunick group at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee.

The structure of the nucleosome core particle is remarkably conserved, and even a change of over 100 residues between frog and yeast histones results in electron density maps with an overall root mean square deviation of only 1.6Å.

Histones dimerise about their long α2 helices in an anti-parallel orientation, and, in the case of H3 and H4, two such dimers form a 4-helix bundle stabilised by extensive H3-H3' interaction.

[31] Direct protein - DNA interactions are not spread evenly about the octamer surface but rather located at discrete sites.

This interaction is thought to occur under physiological conditions also, and suggests that acetylation of the H4 tail distorts the higher-order structure of chromatin.

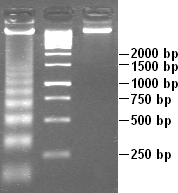

The current understanding[25] is that repeating nucleosomes with intervening "linker" DNA form a 10-nm-fiber, described as "beads on a string", and have a packing ratio of about five to ten.

[18] A chain of nucleosomes can be arranged in a 30 nm fiber, a compacted structure with a packing ratio of ~50[18] and whose formation is dependent on the presence of the H1 histone.

[35] Beyond this, the structure of chromatin is poorly understood, but it is classically suggested that the 30 nm fiber is arranged into loops along a central protein scaffold to form transcriptionally active euchromatin.

Nucleosome positions are controlled by three major contributions: First, the intrinsic binding affinity of the histone octamer depends on the DNA sequence.

[40] This implies that DNA does not need to be actively dissociated from the nucleosome but that there is a significant fraction of time during which it is fully accessible.

[41] This propensity for DNA within the nucleosome to "breathe" has important functional consequences for all DNA-binding proteins that operate in a chromatin environment.

[40] In particular, the dynamic breathing of nucleosomes plays an important role in restricting the advancement of RNA polymerase II during transcription elongation.

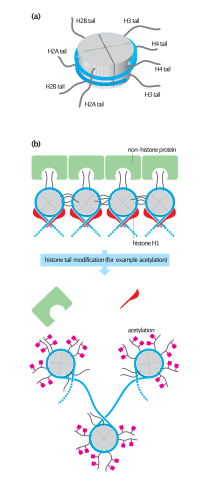

In order to achieve the high level of control required to co-ordinate nuclear processes such as DNA replication, repair, and transcription, cells have developed a variety of means to locally and specifically modulate chromatin structure and function.

The first of the theories suggested that they may affect electrostatic interactions between the histone tails and DNA to "loosen" chromatin structure.

H2A can be replaced by H2AZ (which leads to reduced nucleosome stability) or H2AX (which is associated with DNA repair and T cell differentiation), whereas the inactive X chromosomes in mammals are enriched in macroH2A.

While the consequences of this for the reaction mechanism of chromatin remodeling are not known, the dynamic nature of the system may allow it to respond faster to external stimuli.

[63] The results suggested that nucleosomes that were localized to promoter regions are displaced in response to stress (like heat shock).

The tension is released when the sliding of DNA has been completed throughout the nucleosome via the spread of two twist defects (one on each strand) in opposite directions.

[72] A recent advance in the production of nucleosome core particles with enhanced stability involves site-specific disulfide crosslinks.

A first one crosslinks the two copies of H2A via an introduced cysteine (N38C) resulting in histone octamer which is stable against H2A/H2B dimer loss during nucleosome reconstitution.

A second crosslink can be introduced between the H3 N-terminal histone tail and the nucleosome DNA ends via an incorporated convertible nucleotide.

They serve as a scaffold for formation of higher order chromatin structure as well as for a layer of regulatory control of gene expression.

[80] The nucleosomes are also spaced by ATP-dependent nucleosome-remodeling complexes containing enzymes such as Isw1 Ino80, and Chd1, and subsequently assembled into higher order structure.

[81][82] The crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle (PDB: 1EQZ[28]) - different views showing details of histone folding and organization.