Nucleosynthesis

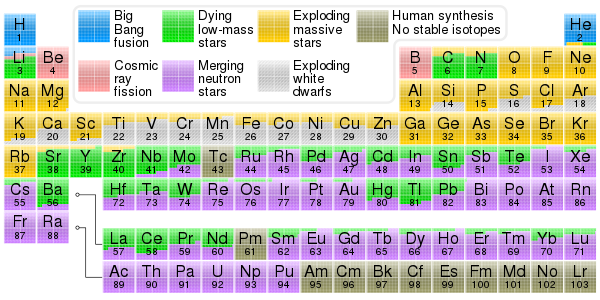

Nucleosynthesis in stars and their explosions later produced the variety of elements and isotopes that we have today, in a process called cosmic chemical evolution.

The amounts of total mass in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium (called 'metals' by astrophysicists) remains small (few percent), so that the universe still has approximately the same composition.

When two neutron stars collide, a significant amount of neutron-rich matter may be ejected which then quickly forms heavy elements.

Cosmic ray spallation can occur in the interstellar medium, on asteroids and meteoroids, or on Earth in the atmosphere or in the ground.

It is thought that the primordial nucleons themselves were formed from the quark–gluon plasma around 13.8 billion years ago during the Big Bang as it cooled below two trillion degrees.

A few minutes afterwards, starting with only protons and neutrons, nuclei up to lithium and beryllium (both with mass number 7) were formed, but hardly any other elements.

That fusion process essentially shut down at about 20 minutes, due to drops in temperature and density as the universe continued to expand.

This first process, Big Bang nucleosynthesis, was the first type of nucleogenesis to occur in the universe, creating the so-called primordial elements.

Interstellar gas therefore contains declining abundances of these light elements, which are present only by virtue of their nucleosynthesis during the Big Bang, and also cosmic ray spallation.

The first ideas on nucleosynthesis were simply that the chemical elements were created at the beginning of the universe, but no rational physical scenario for this could be identified.

In the years immediately before World War II, Hans Bethe first elucidated those nuclear mechanisms by which hydrogen is fused into helium.

Fred Hoyle's original work on nucleosynthesis of heavier elements in stars, occurred just after World War II.

Subsequently, Hoyle's picture was expanded during the 1960s by contributions from William A. Fowler, Alastair G. W. Cameron, and Donald D. Clayton, followed by many others.

The goal of the theory of nucleosynthesis is to explain the vastly differing abundances of the chemical elements and their several isotopes from the perspective of natural processes.

Those abundances, when plotted on a graph as a function of atomic number, have a jagged sawtooth structure that varies by factors up to ten million.

Some of those others include the r-process, which involves rapid neutron captures, the rp-process, and the p-process (sometimes known as the gamma process), which results in the photodisintegration of existing nuclei.

Because of the very short period in which nucleosynthesis occurred before it was stopped by expansion and cooling (about 20 minutes), no elements heavier than beryllium (or possibly boron) could be formed.

Stars are thermonuclear furnaces in which H and He are fused into heavier nuclei by increasingly high temperatures as the composition of the core evolves.

The first direct proof that nucleosynthesis occurs in stars was the astronomical observation that interstellar gas has become enriched with heavy elements as time passed.

Many modern proofs of stellar nucleosynthesis are provided by the isotopic compositions of stardust, solid grains that have condensed from the gases of individual stars and which have been extracted from meteorites.

The creation of free neutrons by electron capture during the rapid compression of the supernova core along with the assembly of some neutron-rich seed nuclei makes the r-process a primary process, and one that can occur even in a star of pure H and He.

The quasi-equilibrium produces radioactive isobars 44Ti, 48Cr, 52Fe, and 56Ni, which (except 44Ti) are created in abundance but decay after the explosion and leave the most stable isotope of the corresponding element at the same atomic weight.

Gamma-ray lines identifying 56Co and 57Co nuclei, whose half-lives limit their age to about a year, proved that their radioactive cobalt parents created them.

In 2017 strong evidence emerged, when LIGO, VIRGO, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and INTEGRAL, along with a collaboration of many observatories around the world, detected both gravitational wave and electromagnetic signatures of a likely neutron star merger, GW170817, and subsequently detected signals of numerous heavy elements such as gold as the ejected degenerate matter decays and cools.

Most notably spallation is believed to be responsible for the generation of almost all of 3He and the elements lithium, beryllium, and boron, although some 7Li and 7Be are thought to have been produced in the Big Bang.

The process results in the light elements beryllium, boron, and lithium in the cosmos at much greater abundances than they are found within solar atmospheres.

Beryllium and boron are not significantly produced by stellar fusion processes, since 8Be has an extremely short half-life of 8.2×10−17 seconds.