Marine sediment

In turn, molten material from the interior returns to the surface of the earth in the form of lava flows and emissions from deep sea hydrothermal vents, ensuring the process continues indefinitely.

Their fossilized remains contain information about past climates, plate tectonics, ocean circulation patterns, and the timing of major extinctions.

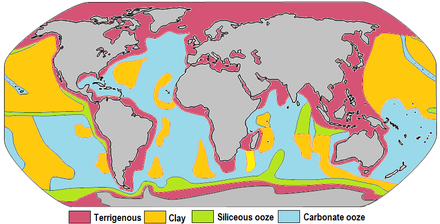

This material comes from several different sources and is highly variable in composition, depending on proximity to a continent, water depth, ocean currents, biological activity, and climate.

These tiny shells, and the even tinier fragments that form when they break into pieces, settle slowly through the water column, but they don't necessarily make it to the bottom.

[1] Gravity: Landslides, mudslides, avalanches, and other gravity-driven events can deposit large amounts of material into the ocean when they happen close to shore.

[1] Volcanoes: Volcanic eruptions emit vast amounts of ash and other debris into the atmosphere, where it can then be transported by wind to eventually get deposited in the oceans.

Sediment particles can then be transported farther by waves and currents, and may eventually escape the continental shelf and reach the deep ocean floor.

This type of sediment is fairly rare over most of the ocean, as large organisms do not die in enough of a concentrated abundance to allow these remains to accumulate.

[1] The primary sources of microscopic biogenous sediments are unicellular algaes and protozoans (single-celled amoeba-like creatures) that secrete tests of either calcium carbonate (CaCO3) or silica (SiO2).

[1] Older calcareous sediment layers contain the remains of another type of organism, the discoasters; single-celled algae related to the coccolithophores that also produced calcium carbonate tests.

This superheated water contains many dissolved substances, and when it encounters the cold seawater after leaving the vent, these particles precipitate out, mostly as metal sulfides.

Therefore, manganese nodules are usually limited to areas in the central ocean, far from significant lithogenous or biogenous inputs, where they can sometimes accumulate in large numbers on the seafloor (Figure 12.4.2 right).

[1] Evaporites are hydrogenous sediments that form when seawater evaporates, leaving the dissolved materials to precipitate into solids, particularly halite (salt, NaCl).

Tiny fragments of this material plus other organic matter from marine plants and animals accumulate in terrigenous sediments, especially within a few hundred kilometres of shore.

As the sediments pile up, the deeper parts start to warm up (from geothermal heat), and bacteria get to work breaking down the contained organic matter.

Although energy corporations and governments are anxious to develop ways to produce and sell this methane, anyone that understands the climate-change implications of its extraction and use can see that this would be folly.

About 90% of incoming cosmogenous debris is vaporized as it enters the atmosphere, but it is estimated that 5 to 300 tons of space dust land on the Earth's surface each day.

[7] Distance from land masses, water depth and ocean fertility are all factors that affect the opal silica content in seawater and the presence of siliceous oozes.

Below this depth, calcium carbonate begins to dissolve in the ocean, and only non-calcareous sediments are stable, such as siliceous ooze or pelagic red clay.

This is because the crust near passive continental margins is often very old, allowing for a long period of accumulation, and because there is a large amount of terrigenous sediment input coming from the continents.

Much of this sediment remains on or near the shelf, while turbidity currents can transport material down the continental slope to the deep ocean floor (abyssal plain).

Thus calcareous oozes will mostly be found in tropical or temperate waters less than about 4 km deep, such as along the mid-ocean ridge systems and atop seamounts and plateaus.

The clay particles are mostly of terrestrial origin, but because they are so small they are easily dispersed by wind and currents, and can reach areas inaccessible to other sediment types.

[18] Also, as a result of supercontinent breakup and other shifting tectonic plate processes, shallow marine sediment displays large variations in terms of quantity in the geologic time.

[22] This type of ecosystem change affects the evolution of cohabitating species and the environment,[22] which is evident in trace fossils left in marine and terrestrial sediments.

[36][37][28] A contourite is a sedimentary deposit commonly formed on continental rise to lower slope settings, although they may occur anywhere that is below storm wave base.

Their now seminal paper [42] demonstrated the very significant effects of contour-following bottom currents in shaping sedimentation on the deep continental rise off eastern North America.

In 2020 it was reported that researchers have examined the chemical composition of thousands of samples of these benthic forams and used their findings to build the most detailed climate record of Earth ever.

In 2020, LaRowe et al. outlined a broad view of this issue that is spread across multiple scientific disciplines related to marine sediments and global carbon cycling.

Later in the 1960s the idea that the seafloor itself moves and also carries the continents with it as it spreads from a central rift axis was proposed by Harold Hess and Robert Dietz.

Within each colored area, the type of material shown is what dominates, although other materials are also likely to be present.

For further information about this diagram see below ↓

Biogeochemists quantify carbon burial and recycling

Organic geochemists study alteration of organic matter

Ecologists focus on carbon as food for organisms living in the sediment

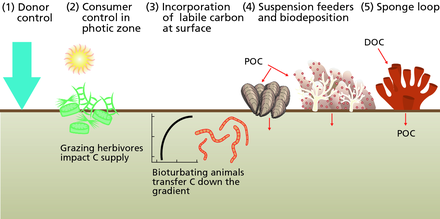

(2) Sediments in the photic zone are inhabited by benthic microalgae that produce new organic matter in situ and grazing animals can impact the growth of these primary producers.

(3) Bioturbating animals transfer labile carbon from the sediment surface layer to deeper layers in the sediments. (Vertical axis is depth; horizontal axis is concentration)

(4) Suspension-feeding organisms enhance the transfer of suspended particulate matter from the water column to the sediments (biodeposition).

(5) Sponge consume dissolved organic carbon and produce cellular debris that can be consumed by benthic organisms (i.e., the sponge loop ). [ 67 ]

of the eons of Earth's history and noting major events