Evolutionary history of plants

By the late Devonian (~370 million years ago) some free-sporing plants such as Archaeopteris had secondary vascular tissue that produced wood and had formed forests of tall trees.

Evidence of the earliest land plants occurs at about 470 million years ago, in lower middle Ordovician rocks from Saudi Arabia[15] and Gondwana[16] in the form of spores known as cryptospores.

Modern bryophytes either avoid it or give in to it, restricting their ranges to moist settings or drying out and putting their metabolism "on hold" until more water arrives, as in the liverwort genus Targionia.

They all bear a waterproof outer cuticle layer wherever they are exposed to air (as do some bryophytes), to reduce water loss, but since a total covering would cut them off from CO2 in the atmosphere tracheophytes use variable openings, the stomata, to regulate the rate of gas exchange.

[citation needed] A global glaciation event called Snowball Earth, from around 720-635 mya in the Cryogenian period, is believed to have been at least partially caused by early photosynthetic organisms, which reduced the concentration of carbon dioxide and decreased the greenhouse effect in the atmosphere,[24] leading to an icehouse climate.

Based on molecular clock studies of the previous decade or so, a 2022 study observed that the estimated time for the origin of the multicellular streptophytes (all except the unicellular basal clade Mesostigmatophyceae) fell in the cool Cryogenian while that of the subsequent separation of streptophytes fell in the warm Ediacaran, which they interpreted as an indication of selective pressure by the glacial period to the photosynthesizing organisms, a group of which succeeded in surviving in relatively warmer environments that remained habitable, subsequently flourishing in the later Ediacaran and Phanerozoic on land as embryophytes.

The observed appearance of larger axial sizes, with room for photosynthetic tissue and thus self-sustainability, provides a possible route for the development of a self-sufficient sporophyte phase.

Like other rootless land plants of the Silurian and early Devonian Aglaophyton may have relied on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for acquisition of water and nutrients from the soil.

Secondly, variable apertures, the stomata that could open and close to regulate the amount of water lost by evaporation during CO2 uptake and thirdly intercellular space between photosynthetic parenchyma cells that allowed improved internal distribution of the CO2 to the chloroplasts.

As plants grew upwards, specialised water transport vascular tissues evolved, first in the form of simple hydroids of the type found in the setae of moss sporophytes.

[45][46] The early Devonian pretracheophytes Aglaophyton and Horneophyton have unreinforced water transport tubes with wall structures very similar to moss hydroids, but they grew alongside several species of tracheophytes, such as Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii that had xylem tracheids that were well reinforced by bands of lignin.

Tracheids have non-perforated end walls with pits, which impose a great deal of resistance on water flow,[50] but may have had the advantage of isolating air embolisms caused by cavitation or freezing.

Vessels first evolved during the dry, low CO2 periods of the Late Permian, in the horsetails, ferns and Selaginellales independently, and later appeared in the mid Cretaceous in gnetophytes and angiosperms.

Rolf Sattler proposed an overarching process-oriented view that leaves some limited room for both the telome theory and Hagemann's alternative and in addition takes into consideration the whole continuum between dorsiventral (flat) and radial (cylindrical) structures that can be found in fossil and living land plants.

This spread has been linked to the fall in the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations in the Late Paleozoic era associated with a rise in density of stomata on leaf surface.

[54] This would have resulted in greater transpiration rates and gas exchange, but especially at high CO2 concentrations, large leaves with fewer stomata would have heated to lethal temperatures in full sunlight.

[67] One theory, the "enation theory", holds that the microphyllous leaves of clubmosses developed by outgrowths of the protostele connecting with existing enations[1] The leaves of the Rhynie genus Asteroxylon, which was preserved in the Rhynie chert almost 20 million years later than Baragwanathia, had a primitive vascular supply – in the form of leaf traces departing from the central protostele towards each individual "leaf".

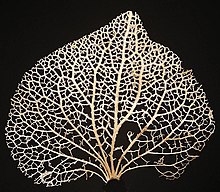

[69] They appear to have originated by modifying dichotomising branches, which first overlapped (or "overtopped") one another, became flattened or planated and eventually developed "webbing" and evolved gradually into more leaf-like structures.

[73] Leaf loss may also have arisen as a response to pressure from insects; it may have been less costly to lose leaves entirely during the winter or dry season than to continue investing resources in their repair.

Unlike the modern horsetail Equisetum, Calamites had a unifacial vascular cambium, allowing them to develop wood and grow to heights in excess of 10 m and to branch repeatedly.

The pollen grain, which contained a microgametophyte germinated from a microspore , was employed for dispersal of the male gamete, only releasing its desiccation-prone flagellate sperm when it reached a receptive megagametophyte.

[83] Likewise, seeds germinating in a gloomy understory require an additional reserve of energy to quickly grow high enough to capture sufficient light for self-sustenance.

[citation needed] Flowers likely emerged during plant evolution as an adaptation to facilitate cross-fertilization (outcrossing), a process that leads to the masking of recessive deleterious mutations in progeny genomes.

For example, Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes that grow in the cold, temperate regions require prolonged vernalization before they flower, while the tropical varieties, and the most common lab strains, don't.

Molecular clock analysis has shown that the other LFY paralog was lost in angiosperms around the same time as flower fossils become abundant, suggesting that this event might have led to floral evolution.

The C4 metabolic pathway is a valuable recent evolutionary innovation in plants, involving a complex set of adaptive changes to physiology and gene expression patterns.

This import is thought to be dependent on the coordination of carbonic anhydrases and anion channels, and takes advantage of the native pH differences between the cytosol, chloroplast stroma, and thylakoid lumen.

[143] Remarkably, some charcoalified fossils preserve tissue organised into the Kranz anatomy, with intact bundle sheath cells,[144] allowing the presence C4 metabolism to be identified.

[142] It is possible that the signal is entirely biological, forced by the fire[153] driven acceleration of grass evolution – which, both by increasing weathering and incorporating more carbon into sediments, reduced atmospheric CO2 levels.

They function in processes as diverse as immunity, anti-herbivory, pollinator attraction, communication between plants, maintaining symbiotic associations with soil flora, or enhancing the rate of fertilization, and hence are significant from the evo-devo perspective.

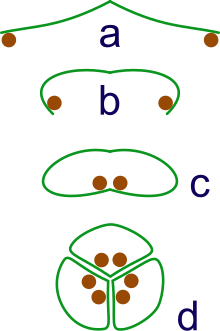

a: sporangia borne at tips of leaf

b: Leaf curls up to protect sporangia

c: leaf curls to form enclosed roll

d: grouping of three rolls into a syncarp