Octant projection

[5] Leonardo's authorship would be demonstrated by Christopher Tyler, who stated "For those projections dated later than 1508,[6] his drawings should be effectively considered the original precursors.

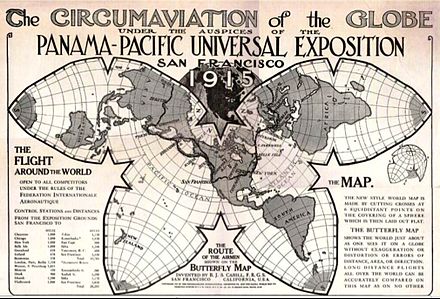

[8] In it, the spherical surface of the earth is divided into eight octants, each flattened into the shape of a Reuleaux triangle bound by circular arcs.

So, bearing in mind the fact that Tyler was the first scholar to mention the sketch of this projection in Codex Atlanticus in 2017, the authorship of the map it is not universally accepted, with some authors being completely against any minimal contribution from Leonardo, such as Henry Harrisse (1892),[15] or Eugène Müntz (1899 – citing Harrisse authority from 1892, although none of them talks about the projection's sketch in Codex Atlanticus).

[16] Other scholars accept explicitly both (map and projection: "the eight of a supposed globe represented in a plane"), completely as a Leonardo's work, describing the projection as the first of this type, among them, R. H. Major (1865) in his work Memoir on a mappemonde by Leonardo da Vinci, being the earliest map hitherto known containing the name of America,[17] Grothe,[18] the Enciclopedia universal ilustrada europeo-americana (1934),[9] Snyder in his book Flattening the Earth (1993),[10] Christopher Tyler in his paper (2014) "Leonardo da Vinci's World Map",[5] José Luis Espejo in his book (2012) Los mensajes ocultos de Leonardo Da Vinci,[19] or David Bower in his work (2012) "The unusual projection for one of John Dee's maps of 1580".

[14] Others also accept explicitly both (map and projection) as authentic, although leaving in the air Leonardo's direct hand, giving the authorship of the work to one of his disciples as Nordenskjold states in his book Facsimile-Atlas (1889) confirmed by Dutton (1995) and many others: "on account of the remarkable projection..not by Leonardo himself, but by some ignorant clerk",[20] or Keunig (1955) being more precise: "by one of his followers at his direction".