Odinala

Although it has largely been syncretised with Catholicism, the indigenous belief system remains in strong effect among the rural, village and diaspora populations of the Igbo.

[6] The number of people practicing Igbo religion decreased drastically in the 20th century with the influx of Christian missionaries under the auspices of the British colonial government in Nigeria.

Igbo religion is most present today in harvest ceremonies such as new yam festival (ị́wá jí) and masquerading traditions such as mmanwụ and Ekpe.

Remnants of Igbo religious rites spread among African descendants in the Caribbean and North America in era of the Atlantic slave trade.

[7][8][9][10] Ọdịnala in central Igbo dialect is the compound of the words ọ̀ dị̀ ('located') + n (nà, 'within') + àla (the one god) [consisting of Elu above (the heavens) and Ala, below (the earth)].

[citation needed] Ọdịnala could loosely be described as a polytheistic and panentheistic faith with a strong central spiritual force at its head from which all things are believed to spring; however, the contextual diversity of the system may encompass various theistic perspectives that derive from a variety of beliefs held within the religion.

Ancestors can offer advice and bestow good fortune and honor to their living dependents, but they can also make demands, such as insisting that their shrines be properly maintained and propitiated.

Monotheism does not reflect the multiplicity of ways that the traditional African spirituality has conceived of deities, gods, and spirit beings.

[24] Around Nkarahia, in southern Igboland, there are the most elaborate chi shrines which are decorated with colourful china plates inset into the clay walls of the chi shrine building; the altars hold sacred emblems, while the polished mud benches hold offerings of china, glass, manillas, and food.

[32] As a marker of personal fortune or misfortune, good acts or ill, chi can be described as a focal point for 'personal religion'.

[35] The days correspond to the four cardinal points and are its names in Igbo, èké east, órìè west, àfọ̀ north, ǹkwọ́ south.

[39] Kola nut is used in ceremonies honour Chukwu, chi, Arusi and ancestors and is used as a method of professing innocence when coupled with libations.

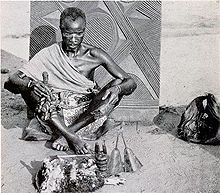

The Igbo often make clay altars and shrines of their deities which are sometimes anthropomorphic, the most popular example being the wooden statues of Ikenga.

Ancestors are protectors and guardians of ones lineage, close friends and heritage, and may become to higher spirits (semi-gods), as in the case of many other traditional religions of the world.

Reincarnation is seldom, but may happen occasionally, if a deceased person cannot enter the spirit world for various reasons or may be absorbed into a new-born if it would die immediately after birth.

In folklore, the ọgbanje, upon being born by the mother, would deliberately die after a certain amount of time (usually before puberty) and then come back and repeat the cycle, causing the family grief.

The child is confirmed to no longer be an ọgbanje after the destruction of the stone or after the mother successfully gives birth to another baby.

[41] Ala (meaning 'earth' and 'land' in Igbo, also Ájá-ànà)[48][49] is the feminine earth spirit who is responsible for morality, fertility and the dead ancestors who are stored in the underworld in her womb.

Ala stands for fertility and things that generate life including water, stone and vegetation, colour (àgwà), beauty (mmá) which is connected to goodness in Igbo society, and uniqueness (ájà).

[19] People who commit suicides are not buried in the ground or given burial rites but cast away in order not to further offend and pollute the land, their ability to become ancestors is therefore nullified.

[19] In some places, such as Nri, the royal python, éké, is considered a sacred and tame agent of Ala and a harbinger of good fortune when found in a home.

[60] He is the expression of divine justice and wrath against taboos and crimes; in oaths he is sworn by and strikes down those who swear falsely with thunder and lightning.

[62] Ikenga (literally 'place of strength') is an Arusi and a cult figure of the right hand and success found among the northern Igbo people.

He is an icon of meditation exclusive to men and owners of the sculpture dedicate and refer to it as their 'right hand' which is considered instrumental to personal power and success.

[20] These choices are at the hands of the persons earth bound spirit, mmuo, who chooses sex, type, and lifespan before incarnation.

Chameleons and rats are used for more stronger medicines and deadly poisons, and antidotes can include lambs, small chickens, eggs, and oils.

Usually this depended on the rarity and price of the animal, so a goat or a sheep were common and relatively cheaper, and therefore carried less prestige, while a cow is considered a great honor, and a horse the most exceptional.

A number of major masking institutions exist around Igboland that honour ancestors and reflect the spirit world in the land of the living.

The mbari house is not a source of worship and is left to dilapidate, being reabsorbed by nature in symbolic sense related to Ala.[31][86] Before the twentieth century, circular stepped pyramids were built in reverence of Ala at the town of Nsude in northern Igboland.

This may satisfy the observer's own theological preferences, e.g., monotheism, but only at the expense of over-systematizing the contextual diversity of African religious thought.Ray, Benjamin C. (1976).