Oil drop experiment

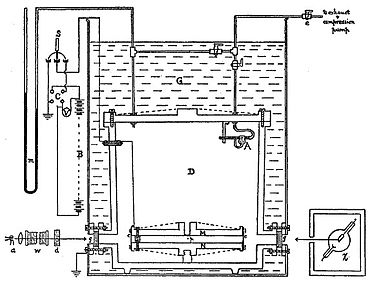

[6] The experiment observed tiny electrically charged droplets of oil located between two parallel metal surfaces, forming the plates of a capacitor.

A mist of atomized oil drops was introduced through a small hole in the top plate and was ionized by x-rays, making them negatively charged.

Starting in 1908, while a professor at the University of Chicago, Millikan, with the significant input of Fletcher,[8] the "able assistance of Mr. J. Yinbong Lee", and after improving his setup, published his seminal study in 1913.

Millikan and Fletcher's experiment involved measuring the force on oil droplets in a glass chamber sandwiched between two electrodes, one above and one below.

At the time of Millikan and Fletcher's oil drop experiments, the existence of subatomic particles was not universally accepted.

Experimenting with cathode rays in 1897, J. J. Thomson had discovered negatively charged "corpuscles", as he called them, with a mass about 1/1837 that of a hydrogen atom.

The elementary charge e is one of the fundamental physical constants and thus the accuracy of the value is of great importance.

Thomas Edison, who had previously thought of charge as a continuous variable, became convinced after working with Millikan and Fletcher's apparatus.

[12] Millikan's and Fletcher's apparatus incorporated a parallel pair of horizontal metal plates.

For a perfectly spherical droplet the apparent weight can be written as: At terminal velocity the oil drop is not accelerating.

Raymond Thayer Birge, conducting a review of physical constants in 1929, stated "The investigation by Bäcklin constitutes a pioneer piece of work, and it is quite likely, as such, to contain various unsuspected sources of systematic error.

[15] Successive X-ray experiments continued to give high results, and proposals for the discrepancy were ruled out experimentally.

Sten von Friesen measured the value with a new electron diffraction method, and the oil drop experiment was redone.

Holton suggested these data points were omitted from the large set of oil drops measured in his experiments without apparent reason.

This claim was disputed by Allan Franklin, a high energy physics experimentalist and philosopher of science at the University of Colorado.

[18][19] Reasons for a failure to generate a complete observation include annotations regarding the apparatus setup, oil drop production, and atmospheric effects which invalidated, in Millikan's opinion (borne out by the reduced error in this set), a given particular measurement.

In a commencement address given at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in 1974 (and reprinted in Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!

in 1985 as well as in The Pleasure of Finding Things Out in 1999), physicist Richard Feynman noted:[20][21] We have learned a lot from experience about how to handle some of the ways we fool ourselves.

One example: Millikan measured the charge on an electron by an experiment with falling oil drops, and got an answer which we now know not to be quite right.