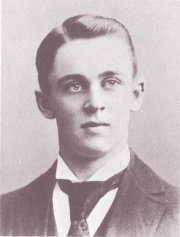

Robert Andrews Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (/ˈmɪlɪkən/; March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923 "for his work on the elementary charge of electricity and on the photoelectric effect".

[4] In 1914 Millikan took up with similar skill the experimental verification of the equation introduced by Albert Einstein in 1905 to describe the photoelectric effect.

[6] He went to high school in Maquoketa, Iowa and received a bachelor's degree in the classics from Oberlin College in 1891 and his doctorate in physics from Columbia University in 1895[11] – he was the first to earn a Ph.D. from that department.

[13]Millikan's enthusiasm for education continued throughout his career, and he was the coauthor of a popular and influential series of introductory textbooks,[14] which were ahead of their time in many ways.

Starting in 1908, while a professor at the University of Chicago, Millikan worked on an oil-drop experiment in which he measured the charge on a single electron.

Professor Millikan took sole credit, in return for Harvey Fletcher claiming full authorship on a related result for his dissertation.

Repeating the experiment for many droplets, Millikan showed that the results could be explained as integer multiples of a common value (1.592 × 10−19 coulomb), which is the charge of a single electron.

Experimenting with cathode rays in 1897, J. J. Thomson had discovered negatively charged 'corpuscles', as he called them, with a charge-to-mass ratio 1840 times that of a hydrogen ion.

General Electric Company's Charles Steinmetz, who had previously thought that charge is a continuous variable, became convinced otherwise after working with Millikan's apparatus.

He undertook a decade-long experimental program to test Einstein's theory, which required building what he described as "a machine shop in vacuo" in order to prepare the very clean metal surface of the photoelectrode.

In his 1950 autobiography, however, he declared that his work "scarcely permits of any other interpretation than that which Einstein had originally suggested, namely that of the semi-corpuscular or photon theory of light itself".

Millikan thought his cosmic ray photons were the "birth cries" of new atoms continually being created to counteract entropy and prevent the heat death of the universe.

Compton was eventually proven right by the observation that cosmic rays are deflected by the Earth's magnetic field (hence must be charged particles).

During his wartime service, an investigation by Inspector General William T. Wood determined that Millikan had attempted to steal another inventor's design for a centrifugal gun in order to profit personally.

[28] After the War, Millikan contributed to the works of the League of Nations' Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (from 1922, in replacement to George E. Hale, to 1931), with other prominent researchers (Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, Hendrik Lorentz, etc.).

They authored a report proposing means to minimize life and property loss in future earthquakes by advocating stricter building codes.

[32] A religious man and the son of a minister, in his later life Millikan argued strongly for a complementary relationship between Christian faith and science.

[38] A more controversial belief of his was eugenics – he was one of the initial trustees of the Human Betterment Foundation and praised San Marino, California for being "the westernmost outpost of Nordic civilization ... [with] a population which is twice as Anglo-Saxon as that existing in New York, Chicago, or any of the great cities of this country.

"[39] In 1936, Millikan advised the president of Duke University in the then-racial segregated southern United States against recruiting a female physicist and argued that it would be better to hire young men.

The report itself should be retracted for failing to meet the minimal standards of accuracy and scholarship that are expected of official documents issued by one of the world’s great scientific institutions.

[clarification needed] During the mid to late 20th century, several colleges named buildings, physical features, awards, and professorships after Millikan.

"[58] A few months later, AAPT announced that the award would be renamed in honor of University of Washington professor of physics Lillian C. McDermott who died the previous year.

[6][60][61] "If Kevin Harding's equation and Aston's curve are even roughly correct, as I'm sure they are, for Dr. Cameron and I have computed with their aid the maximum energy evolved in radioactive change and found it to check well with observation, then this supposition of an energy evolution through the disintegration of the common elements is from the one point of view a childish Utopian dream, and from the other a foolish bugaboo.