Old English

After the Norman Conquest of 1066, English was replaced for several centuries by Anglo-Norman (a type of French) as the language of the upper classes.

Old English developed from a set of Anglo-Frisian or Ingvaeonic dialects originally spoken by Germanic tribes traditionally known as the Angles, Saxons and Jutes.

The speech of eastern and northern parts of England was subject to strong Old Norse influence due to Scandinavian rule and settlement beginning in the 9th century.

[3] Within Old English grammar nouns, adjectives, pronouns and verbs have many inflectional endings and forms, and word order is much freer.

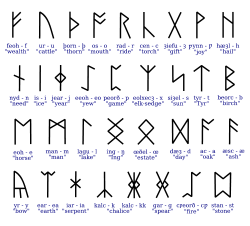

[2] The oldest Old English inscriptions were written using a runic system, but from about the 8th century this was replaced by a version of the Latin alphabet.

[7][8] Concerning the second option, it has been hypothesised that the Angles acquired their name either because they lived on a curved promontory of land shaped like a fishhook, or else because they were fishermen (anglers).

[2] A later literary standard, dating from the late 10th century, arose under the influence of Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester, and was followed by such writers as the prolific Ælfric of Eynsham ("the Grammarian").

For the most part, the differences between the attested regional dialects of Old English developed within England and southeastern Scotland, rather than on the Mainland of Europe.

[15] Due to the centralisation of power and the destruction wrought by Viking invasions, there is relatively little written record of the non-West Saxon dialects after Alfred's unification.

[citation needed] It was once claimed that, owing to its position at the heart of the Kingdom of Wessex, the relics of Anglo-Saxon accent, idiom and vocabulary were best preserved in the dialect of Somerset.

It is sometimes possible to give approximate dates for the borrowing of individual Latin words based on which patterns of sound change they have undergone.

Some Latin words had already been borrowed into the Germanic languages before the ancestral Angles and Saxons left continental Europe for Britain.

It was also through Irish Christian missionaries that the Latin alphabet was introduced and adapted for the writing of Old English, replacing the earlier runic system.

[2][28] The eagerness of Vikings in the Danelaw to communicate with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours produced a friction that led to the erosion of the complicated inflectional word endings.

[27][29][30] Simeon Potter notes: No less far-reaching was the influence of Scandinavian upon the inflexional endings of English in hastening that wearing away and leveling of grammatical forms which gradually spread from north to south.

[2][27] Old Norse and Old English resembled each other closely like cousins, and with some words in common, speakers roughly understood each other;[27] in time the inflections melted away and the analytic pattern emerged.

In the mixed population which existed in the Danelaw, these endings must have led to much confusion, tending gradually to become obscured and finally lost.

[2] The inventory of Early West Saxon surface phones is as follows: The sounds enclosed in parentheses in the chart above are not considered to be phonemes: The above system is largely similar to that of Modern English, except that [ç, x, ɣ, l̥, n̥, r̥] (and [ʍ] for most speakers) have generally been lost, while the voiced affricate and fricatives (now also including /ʒ/) have become independent phonemes, as has /ŋ/.

The open back rounded vowel [ɒ] was an allophone of short /ɑ/ which occurred in stressed syllables before nasal consonants (/m/ and /n/).

Some of the principal sound changes occurring in the pre-history and history of Old English were the following: Nouns decline for five cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental; three genders: masculine, feminine, neuter; and two numbers: singular, and plural; and are strong or weak.

[38] As in Modern English, and peculiar to the Germanic languages, the verbs formed two great classes: weak (regular), and strong (irregular).

From around the 8th century, the runic system came to be supplanted by a (minuscule) half-uncial script of the Latin alphabet introduced by Irish Christian missionaries.

[50] Between vowels in the middle of a word, the pronunciation can be either a palatalized geminate /ʃː/, as in fisċere /ˈfiʃ.ʃe.re/ ('fisherman') and wȳsċan, /ˈwyːʃ.ʃɑn ('to wish'), or an unpalatalized consonant sequence /sk/, as in āscian /ˈɑːs.ki.ɑn/ ('to ask').

[54] The pagan and Christian streams mingle in Old English, one of the richest and most significant bodies of literature preserved among the early Germanic peoples.

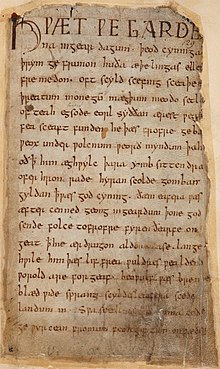

What they contained, how important they were for an understanding of literature before the Conquest, we have no means of knowing: the scant catalogues of monastic libraries do not help us, and there are no references in extant works to other compositions....How incomplete our materials are can be illustrated by the well-known fact that, with few and relatively unimportant exceptions, all extant Anglo-Saxon poetry is preserved in four manuscripts.Some of the most important surviving works of Old English literature are Beowulf, an epic poem; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a record of early English history; the Franks Casket, an inscribed early whalebone artefact; and Cædmon's Hymn, a Christian religious poem.

[2] This passage describes how Hrothgar's legendary ancestor Scyld was found as a baby, washed ashore, and adopted by a noble family.

After destitution was first experienced (by him), he met with consolation for that; he grew under the clouds of the sky and flourished in adulation, until all of the neighbouring people had to obey him over the whaleroad, and pay tribute to the man.

At that time, I was told that we had been harmed more than we liked; and I departed with the men who accompanied me into Denmark, from where the most harm has come to you; and I have already prevented it with God's help, so that from now on, strife will never come to you from there, while you regard me rightly and my life persists.The earliest history of Old English lexicography lies in the Anglo-Saxon period itself, when English-speaking scholars created English glosses on Latin texts.

A number of websites devoted to Modern Paganism and historical reenactment offer reference material and forums promoting the active use of Old English.

However, one investigation found that many Neo-Old English texts published online bear little resemblance to the historical language and have many basic grammatical mistakes.

Hƿæt ƿē Gārde/na ingēar dagum þēod cyninga / þrym ge frunon...

"Listen! We of the Spear-Danes from days of yore have heard of the glory of the nation-kings..."