Old Japanese

It became Early Middle Japanese in the succeeding Heian period, but the precise delimitation of the stages is controversial.

The other major literary sources of the period are the 128 songs included in the Nihon Shoki (720) and the Man'yōshū (c. 759), a compilation of over 4,500 poems.

The latter has the virtue of being an original inscription, whereas the oldest surviving manuscripts of all the other texts are the results of centuries of copying, with the attendant risk of scribal errors.

[4][6] A limited number of Japanese words, mostly personal names and place names, are recorded phonetically in ancient Chinese texts, such as the "Wei Zhi" portion of the Records of the Three Kingdoms (3rd century AD), but the transcriptions by Chinese scholars are unreliable.

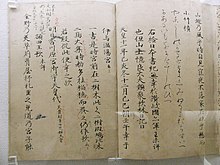

The tablets bear short texts, often in Old Japanese of a more colloquial style than the polished poems and liturgies of the primary corpus.

Later "hybrid" texts show the influence of Japanese grammar, such as the word order (for example, the verb being placed after the object).

In Japan, the practice was developed into man'yōgana, a complete script for the language that used Chinese characters phonetically, which was the ancestor of modern kana syllabaries.

Shinkichi Hashimoto discovered in 1917 that many syllables that have a modern i, e or o occurred in two forms, termed types A (甲, kō) and B (乙, otsu).

[32] Conversely, syllables consisting of a single vowel were restricted to word-initial position, with a few exceptions such as kai 'oar', ko2i 'to lie down', kui 'to regret' (with conclusive kuyu), oi 'to age' and uuru, the adnominal form of the verb uwe 'to plant'.

[37] The mokkan typically did not distinguish voiced from voiceless consonants, and wrote some syllables with characters that had fewer strokes and were based on older Chinese pronunciations imported via the Korean peninsula.

For example, Several different notations for the type A/B distinction are found in the literature, including:[39][40][41] There is no consensus on the pronunciation of the syllables distinguished by man'yōgana.

[43] Additional evidence has been drawn from phonological typology, subsequent developments in the Japanese pronunciation, and the comparative study of the Ryukyuan languages.

[44] Miyake reconstructed the following consonant inventory:[45] The voiceless obstruents /p, t, s, k/ had voiced prenasalized counterparts /ᵐb, ⁿd, ⁿz, ᵑɡ/.

[45] Prenasalization was still present in the late 17th century (according to the Korean textbook Ch'ŏphae Sinŏ) and is found in some Modern Japanese and Ryukyuan dialects, but it has disappeared in modern Japanese except for the intervocalic nasal stop allophone [ŋ] of /ɡ/.

[47] Comparative evidence from Ryukyuan languages suggests that Old Japanese p reflected an earlier voiceless bilabial stop *p.[48] There is general agreement that word-initial p had become a voiceless bilabial fricative [ɸ] by Early Modern Japanese, as suggested by its transcription as f in later Portuguese works and as ph or hw in the Korean textbook Ch'ŏphae Sinŏ.

[53] Others, beginning in the 1930s but more commonly since the work of Roland Lange in 1968, have attributed the type A/B distinction to medial or final glides /j/ and /w/.

[54][40] The diphthong proposals are often connected to hypotheses about pre-Old Japanese, but all exhibit an uneven distribution of glides.

[citation needed] Although modern Japanese dialects have pitch accent systems, they were usually not shown in man'yōgana.

However, in one part of the Nihon Shoki, the Chinese characters appeared to have been chosen to represent a pitch pattern similar to that recorded in the Ruiju Myōgishō, a dictionary that was compiled in the late 11th century.

(A similar division was used in the tone patterns of Chinese poetry, which were emulated by Japanese poets in the late Asuka period.)

Some scholars have interpreted that as a vestige of earlier vowel harmony, but it is very different from patterns that are observed in, for example, the Turkic languages.

[73] Internal reconstruction suggests that the Old Japanese voiced obstruents, which always occurred in medial position, arose from the weakening of earlier nasal syllables before voiceless obstruents:[74][75] In some cases, such as tubu 'grain', kadi 'rudder' and pi1za 'knee', there is no evidence for a preceding vowel, which leads some scholars to posit final nasals at the earlier stage.

[76] Southern Ryukyuan varieties such as Miyako, Yaeyama and Yonaguni have /b/ corresponding to Old Japanese w, but only Yonaguni (at the far end of the chain) has /d/ where Old Japanese has y:[77] However, many linguists, especially in Japan, argue that the Southern Ryukyuan voiced stops are local innovations,[78] adducing a variety of reasons.

[82] Some authors believe that they belong to an earlier layer than i2 < *əi, but others reconstruct two central vowels *ə and *ɨ, which merged everywhere except before *i.

[115] Old Japanese nominals had suffixes or particles to mark diminutives, plural number and case.

[123] There are a few cases in the Senmyō of subjects of active verbs marked with a suffix -i, which is thought to be an archaism that was obsolete in the Old Japanese period.

[145] Three of the classes are grouped as consonant bases:[146] The distinctions between i1 and i2 and between e1 and e2 were eliminated after s, z, t, d, n, y, r and w. There were five vowel-base conjugation classes: Early Middle Japanese also had a Shimo ichidan (lower monograde or e-monograde) category, consisting of a single verb kwe- 'kick', which reflected the Old Japanese lower bigrade verb kuwe-.

[165] Japanese has used verbal prefixes conveying emphasis at all stages, but Old Japanese also had prefixes expressing grammatical functions, such as reciprocal or cooperative api1- (from ap- 'meet, join'), stative ari- (from ar- 'exist'), potential e2- (from e2- 'get') and prohibitive na-, which was often combined with a suffix -so2.

[126][178] Other auxiliaries were attached to the irrealis stem: Old Japanese adjectives were originally nominals and, unlike in later periods, could be used uninflected to modify following nouns.

[201] The semantic effect (though not the syntactic structure) was often similar to a cleft sentence in English:[202] wa1SgaGENko1purulove.ADNki1mi1lordso2FOCki1zolast.nightno2GENyo1nightime2dreamniDATmi1-ye-turusee-PASS-PERF.ADNwa ga ko1puru ki1mi1 so2 ki1zo no2 yo1 ime2 ni mi1-ye-turu1S GEN love.ADN lord FOC last.night GEN night dream DAT see-PASS-PERF.ADN'It was my beloved lord that I saw last night in a dream.'