Margarine

The spread was originally named oleomargarine from Latin for oleum (olive oil) and Greek margarite ("pearl", indicating luster).

[3][4] Margarine consists of a water-in-fat emulsion, with tiny droplets of water dispersed uniformly throughout a fat phase in a stable solid form.

[11] After the French Emperor Napoleon III issued a challenge to create a butter-substitute from beef tallow for the armed forces and lower classes, Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès invented margarine in 1869.

[2][12] Mège-Mouriès patented the product, which he named "oleomargarine", and expanded his initial manufacturing operation from France, but had little commercial success.

[2][13] In the same year a German pharmacist, Benedict Klein from Cologne, founded the first margarine factory in Germany, producing the brands Overstolz and Botteram.

[2] Shortages in beef-fat supply, combined with advances by James F. Boyce and Paul Sabatier in the hydrogenation of plant materials, soon accelerated the use of Bradley's method, and between 1900 and 1920, commercial oleomargarine was produced from a combination of animal fats and hardened and unhardened vegetable oils.

[2] Dairy firms, especially in Wisconsin, became alarmed at the potential threat to their business, and succeeded in getting legislation passed to prohibit the coloring of the stark white margarine by 1902.

[2][20] In 1951, the W. E. Dennison Company received US Patent 2553513[21] for a method to place a capsule of yellow dye inside a plastic package of margarine.

[2] Around the 1930s and 1940s, Arthur Imhausen developed and implemented an industrial process in Germany for producing edible fats by oxidizing synthetic paraffin wax made from coal.

[24] Margarine made from them was found to be nutritious and of agreeable taste, and it was incorporated into diets contributing as much as 700 calories per day.

[5] In 1978, an 80% fat product called Krona, made by churning a blend of dairy cream and vegetable oils, was introduced in Europe and, in 1982, a blend of cream and vegetable oils called Clover was introduced in the UK by the Milk Marketing Board.

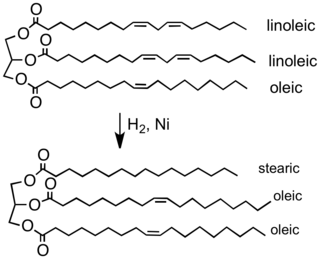

[2] The basic method of making margarine today consists of emulsifying a blend of oils and fats from vegetable and animal sources, which can be modified using fractionation, interesterification or hydrogenation, with skimmed milk which may be fermented or soured, salt, citric or lactic acid, chilling the mixture to solidify it, and working it to improve the texture.

However, as there are possible health benefits in limiting the amount of saturated fats in the human diet, the process is controlled so that only enough of the bonds are hydrogenated to give the required texture.

If these particular bonds are not hydrogenated during the process, they remain present in the final margarine in molecules of trans fats,[33] the consumption of which has been shown to be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

[35][36] In a 100-gram reference amount, margarine – manufactured from soybean oil and pasteurized – provides 628 kilocalories (2,630 kJ) and is composed of 70% fat, 2% carbohydrates, 26% water, and negligible protein.

[49] The American Institute of Medicine and the European Food Safety Authority recommend saturated fat intake to be as low as possible.

[55] Several large studies have indicated a link between consumption of high amounts of trans fat and coronary heart disease, and possibly some other diseases,[42][56][57][58] prompting a number of government health agencies across the world to recommend that the intake of trans fats be minimized.

[68] Regular margarine contains trace amounts of animal products such as whey or dairy casein extracts.

Sales of the product have decreased in recent years due to consumers "reducing their use of spreads in their daily diet".

[70] Butter-colored margarine was sold from its introduction in Australia, but dairy and associated industries lobbied governments strongly in a vain attempt to have them change its color, or ban it altogether.

"[73] In 2007, Health Canada released an updated version of Canada's Food Guide that recommended Canadians choose "soft" margarine spreads that are low in saturated and trans fats and limit traditional "hard" margarines, butter, lard, and shortening in their diets.

Many member states currently require the mandatory addition of vitamins A and D to margarine and fat spreads for reasons of public health.

That year, Newfoundland negotiated its entry into the Canadian Confederation, and one of its three non-negotiable conditions for union with Canada was a constitutional protection for the new province's right to manufacture margarine.

The law, "to prevent deception in sales of butter," required retailers to provide customers with a slip of paper that identified the "imitation" product as margarine.

By the mid-1880s, the U.S. federal government had introduced a tax of two cents per pound, and manufacturers needed an expensive license to make or sell the product.

The simple expedient of requiring oleo manufacturers to color their product distinctively was, however, left out of early federal legislation.

In several states, legislatures enacted laws to require margarine manufacturers to add pink colorings[87] to make the product look unpalatable, despite the objections of the oleo manufacturers that butter dairies themselves added annatto to their product to imitate the yellow of mid-summer butter.

Nevertheless, the regulations and taxes had a significant effect: the 1902 restrictions on margarine color, for example, cut annual consumption in the United States from 120,000,000 to 48,000,000 pounds (54,000 to 22,000 t).

[89] With the coming of World War I, margarine consumption increased enormously, even in countries away from the front, such as the United States.

The United Kingdom, for example, depended on imported butter from Australia and New Zealand, and the risk of submarine attacks meant little arrived.