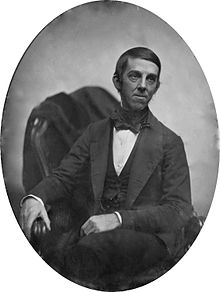

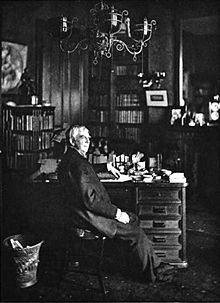

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

[5] He also enjoyed exploring his father's library, writing later in life that "it was very largely theological, so that I was walled in by solemn folios making the shelves bend under the load of sacred learning.

Since he measured only "five feet three inches when standing in a pair of substantial boots",[14] the young student had no interest in joining a sports team or the Harvard Washington Corps.

[30] His last major poem that year was "The Last Leaf", which was inspired in part by a local man named Thomas Melvill, "the last of the cocked hats" and one of the "Indians" from the 1774 Boston Tea Party.

Holmes would later write that Melvill had reminded him of "a withered leaf which has held to its stem through the storms of autumn and winter, and finds itself still clinging to its bough while the new growths of spring are bursting their buds and spreading their foliage all around it.

Later he would write that he had "tasted the intoxicating pleasure of authorship" but compared such contentment to a sickness, saying: "there is no form of lead-poisoning which more rapidly and thoroughly pervades the blood and bones and marrow than that which reaches the young author through mental contact with type metal".

Dismayed by the "painful and repulsive aspects" of primitive medical treatment of the time—which included practices such as bloodletting and blistering—Holmes responded favorably to his mentor's teachings, which emphasized close observation of the patient and humane approaches.

"[41] At the hospital of La Pitié, he studied under internal pathologist Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis, who demonstrated the ineffectiveness of bloodletting, which had been a mainstay of medical practice since antiquity.

In the book's introduction, he mused: "Already engaged in other duties, it has been with some effort that I have found time to adjust my own mantle; and I now willingly retire to more quiet labors, which, if less exciting, are more certain to be acknowledged as useful and received with gratitude".

[47] He also gained a greater reputation after winning Harvard Medical School's prestigious Boylston Prize, for which he submitted a paper on the benefits of using the stethoscope, a device with which many American doctors were not familiar.

[62] The essay argued—contrary to popular belief at the time, which predated germ theory of disease—that the cause of puerperal fever, a deadly infection contracted by women during or shortly after childbirth, stems from patient-to-patient contact via their physicians.

[62] In a new introduction, in which Holmes directly addressed his opponents, he wrote: "I had rather rescue one mother from being poisoned by her attendant, than claim to have saved forty out of fifty patients to whom I had carried the disease.

"[70] A few years later, Ignaz Semmelweis would reach similar conclusions in Vienna, where his introduction of prophylaxis (handwashing in chlorine solution before assisting at delivery) would considerably lower the puerperal mortality rate, and the then-controversial work is now considered a landmark in germ theory of disease.

[74] Holmes's training in Paris led him to teach his students the importance of anatomico-pathological basis of disease, and that "no doctrine of prayer or special providence is to be his excuse for not looking straight at secondary causes.

Then silence, and there begins a charming hour of description, analysis, anecdote, harmless pun, which clothes the dry bones with poetic imagery, enlivens a hard and fatiguing day with humor, and brightens to the tired listener the details for difficult though interesting study.

This new magazine was edited by Holmes's friend James Russell Lowell, and articles were contributed by the New England literary elite such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Lothrop Motley and J. Elliot Cabot.

Based upon fictionalized breakfast table talk and including poetry, stories, jokes and songs,[93] the work was favored by readers and critics alike and it secured the initial success of The Atlantic Monthly.

[98] Originally entitled "The Professor's Story", the novel is about a neurotic young woman whose mother was bitten by a rattlesnake while pregnant, making her daughter's personality half-woman, half-snake.

[99] The novel drew a wide range of comments, including praise from John Greenleaf Whittier and condemnation from church papers, which claimed the work a product of heresy.

[102] About 1860, Holmes invented the "American stereoscope", a 19th-century entertainment in which pictures were viewed in 3-D.[103] He later wrote an explanation for its popularity, stating: "There was not any wholly new principle involved in its construction, but, it proved so much more convenient than any hand-instrument in use, that it gradually drove them all out of the field, in great measure, at least so far as the Boston market was concerned.

[117] Written fifteen years after The Autocrat, this work's tone was mellower and more nostalgic than its predecessor; "As people grow older," Holmes wrote, "they come at length to live so much in memory that they often think with a kind of pleasure of losing their dearest possessions.

[118] In 1876, at the age of seventy, Holmes published a biography of John Lothrop Motley, which was an extension of an earlier sketch he had written for the Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings.

[133] A month later, Holmes wrote to Harvard president Charles William Eliot that the university should consider adopting the honorary doctor of letters degree and offer one to Samuel Francis Smith, though one was never issued.

[146] Critic George Warren Arms believed Holmes's poetry to be provincial in nature, noting his "New England homeliness" and "Puritan familiarity with household detail" as proof.

[147] In his poetry, Holmes often connected the theme of nature to human relations and social teachings; poems such as "The Ploughman" and "The New Eden", which were delivered in commemoration of Pittsfield's scenic countryside, were even quoted in the 1863 edition of the Old Farmer's Almanac.

He further stated that although the author's earlier works (The Autocrat and The Professor of the Breakfast-Table) are "virile and fascinating", later ones such as Our Hundred Days in Europe and Over the Teacups "have little distinction of style to recommend them.

[155] These three table-talk books attracted a diverse audience due to their conversational style, which made readers feel an intimate connection to the author, and resulted in a flood of letters from admirers.

[156] The series' conversational tone is not only meant to mimic the philosophical debates and pleasantries that occur around the breakfast table, but it is also used in order to facilitate an openness of thought and expression.

[161] Holmes wrote in the second preface to Elsie Venner, his first novel, that his aim in writing the work was "to test the doctrine of 'original sin' and human responsibility for the distorted violation coming under that technical denomination".

[171] Though he was popular at the national level, Holmes promoted Boston culture and often wrote from a Boston-centric point of view, believing the city was "the thinking centre of the continent, and therefore of the planet".

[174] Emerson noted that, though Holmes did not renew his focus on poetry until later in his life, he quickly perfected his role "like old pear trees which have done nothing for ten years, and at last begin to grow great.