Eli Whitney

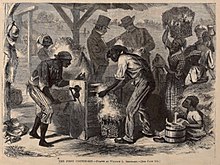

[1] Whitney's invention made upland short cotton into a profitable crop, which strengthened the economic foundation of slavery in the United States and prolonged the institution.

Despite the social and economic impact of his invention, Whitney lost much of his profits in legal battles over patent infringement for the cotton gin.

[1][4] Whitney expected to study law but, finding himself short of funds, accepted an offer to go to South Carolina as a private tutor.

[3] In the closing years of the 18th century, Georgia was a magnet for New Englanders seeking their fortunes (its Revolutionary-era governor had been Lyman Hall, a migrant from Connecticut).

Her plantation manager and husband-to-be was Phineas Miller, another Connecticut migrant and Yale graduate (class of 1785), who would become Whitney's business partner.

Whitney is most famous for two innovations which came to have significant impacts on the United States in the mid-19th century: the cotton gin (1793) and his advocacy of interchangeable parts.

Conversely, in the North the adoption of interchangeable parts revolutionized the manufacturing industry, contributing greatly to the U.S. victory in the Civil War.

While staying at Mulberry Grove, Whitney constructed several ingenious household devices which led Mrs Greene to introduce him to some businessmen who were discussing the desirability of a machine to separate the short staple upland cotton from its seeds, work that was then done by hand at the rate of a pound of lint a day.

Whitney believed that his cotton gin would reduce the demand for enslaved labor and would help hasten the end of southern slavery.

[13] Paradoxically, the cotton gin, a labor-saving device, helped preserve and prolong slavery in the United States for another 70 years.

But with the invention of the gin, growing cotton with slave labor became highly profitable – the chief source of wealth in the American South, and the basis of frontier settlement from Georgia to Texas.

Attempts at interchangeability of parts can be traced back as far as the Punic Wars through both archaeological remains of boats now in Museo Archeologico Baglio Anselmi and contemporary written accounts.

An early leader was Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval, an 18th-century French artillerist who created a fair amount of standardization of artillery pieces, although not true interchangeability of parts.

Ten months later, the Treasury Secretary, Oliver Wolcott Jr., sent him a "foreign pamphlet on arms manufacturing techniques," possibly one of Honoré Blanc's reports, after which Whitney first began to talk about interchangeability.

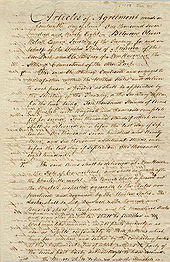

In May 1798, Congress voted for legislation that would use 800,000 dollars in order to pay for small arms and cannons in case war with France erupted.

Recently, historians have found that during 1801–1806, Whitney took the money and headed into South Carolina in order to profit from the cotton gin.

[15] Although Whitney's demonstration of 1801 appeared to show the feasibility of creating interchangeable parts, Merritt Roe Smith concludes that it was "staged" and "duped government authorities" into believing that he had been successful.

In building his arms business, he took full advantage of the access that his status as a Yale alumnus gave him to other well-placed graduates, such as Oliver Wolcott Jr., Secretary of the Treasury (class of 1778), and James Hillhouse, a New Haven developer and political leader.