On Sizes and Distances (Hipparchus)

On Sizes and Distances (of the Sun and Moon) (Greek: Περὶ μεγεθῶν καὶ ἀποστημάτων [ἡλίου καὶ σελήνης], romanized: Peri megethon kai apostematon) is a text by the ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus (c. 190 – c. 120 BC) in which approximations are made for the radii of the Sun and the Moon as well as their distances from the Earth.

It is not extant, but some of its contents have been preserved in the works of Ptolemy and his commentator Pappus of Alexandria.

The work is also mentioned by Theon of Smyrna and others, but their accounts have proven less useful in reconstructing the procedures of Hipparchus.

In Almagest V, 11, Ptolemy writes: This passage gives a general outline of what Hipparchus did, but provides no details.

The works of Hipparchus were still extant when Pappus wrote his commentary on the Almagest in the 4th century.

Several historians of science have attempted to reconstruct the calculations involved in On Sizes and Distances.

Friedrich Hultsch determined in a 1900 paper that the Pappus source had been miscopied, and that the actual distance to the Sun, as calculated by Hipparchus, had been 2490 Earth radii (not 490).

Assuming that this refers to volumes, it follows that and Assuming that the Sun and Moon have the same apparent size in the sky, and that the Moon is 671⁄3 Earth radii distant, it follows that This result was generally accepted for the next seventy years, until Noel Swerdlow reinvestigated the case.

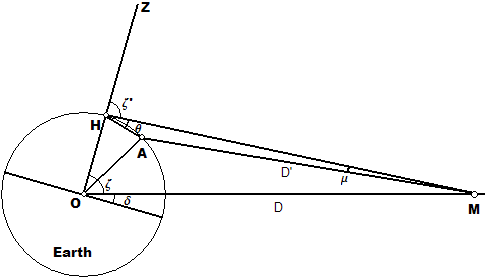

Swerdlow determined that Hipparchus relates the distances to the Sun and Moon using a construction found in Ptolemy.

It would not be surprising if this calculation had been originally developed by Hipparchus himself, as he was a primary source for the Almagest.

Using simple trigonometric identities gives and By parallel lines and taking t = 1, we get By similarity of triangles, Combining these equations gives The values which Hipparchus took for these variables can be found in Ptolemy's Almagest IV, 9.

Following Pappus and Ptolemy, Swerdlow suggested that Hipparchus had estimated 490 Earth radii as a minimum possible distance to the Sun.

This distance corresponds to a solar parallax of 7', which may have been the maximum that he thought would have gone unnoticed (the typical resolution of the human eye is 2').

Because he knew the value which Hipparchus eventually gave for the distance to the Moon (71 Earth radii) and the rough region of the eclipse, Toomer was able to determine that Hipparchus used the solar eclipse of March 14, 190 BC.

This eclipse fits all the mathematical parameters very well, and also makes sense from a historical point of view.

Assuming that these reconstructions accurately reflect what Hipparchus wrote in On Sizes and Distances, then this work was a remarkable accomplishment.

This approach of setting limits on an unknown physical quantity was not new to Hipparchus (see Aristarchus of Samos.

Archimedes also did the same with pi), but in those cases, the bounds reflected the inability to determine a mathematical constant to an arbitrary precision, not uncertainty in physical observations.

His aim in calculating the distance to the Moon was to obtain an accurate value for the lunar parallax, so that he might predict eclipses with more precision.

Combining the calculations of Book 2 and the account of Theon of Smyrna yields a lunar distance of 60.5 Earth radii.