Opera in Scotland

Italian, French, English and German operas have served as models, even when composers sought to introduce characteristically national elements into their work.

[4] From the late-Victorian period onwards, opera-loving Scots had to make do with the offerings of small or family-based companies that toured extensively throughout the British Isles.

Digitisation of newspapers, magazines and other print media helps researchers in some respects but nationally this process is still a long way from being complete.

National and local libraries and even specialist archives of performing arts material tend to hold only a haphazard handful of programmes or other memorabilia.

Attempts must therefore be made to identify and build the detail of early performances and casts using mainly newspaper reviews, programmes and playbills.

An ambitious attempt to pursue this online, and unique in trying to work nationally rather than in relation to a single company, is that of OperaScotland, a website for listings and performance history.

[7] Professor Alexander Weatherson, writing in the February 2009 Donizetti Society Newsletter, notes the following (with the addition of relevant opera titles associated with the named composers): Other notable non-Scottish composers of operas on Scottish subjects include Bizet, Handel, Giacomo Meyerbeer, Jean-François Le Sueur, John Barnett and Giuseppe Verdi.

Richard Wagner originally set the action of his music drama The Flying Dutchman in Scotland, but changed the location to Norway shortly before its premiere staged in Dresden in January 1843.

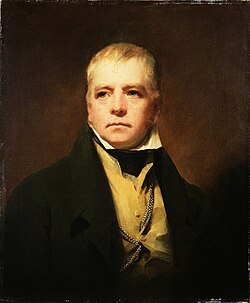

The works of Walter Scott proved popular with nineteenth-century composers, and "the Scottish play" Macbeth by English playwright William Shakespeare has also been adapted several times.

A list of over forty stage works based on this novel may be found in an appendix of Jeff Dailey's study of Sullivan's opera.

He is best known as the subject of William Shakespeare's tragedy Macbeth and the many works it has inspired, although the play presents a highly inaccurate picture of his reign and personality.

In 1760 Macpherson published the English-language text Fragments of ancient poetry, collected in the Highlands of Scotland, and translated from the Gaelic or Erse language.

Later that year Macpherson announced that he had obtained further manuscripts of ancient Gaelic poetry and in 1761 reported his discovery of an epic on the subject of the hero Fingal, said to be the work of a blind Celtic bard named Ossian.

[14] Many writers were influenced by the poem, including the young Walter Scott, and several painters and composers depicted Ossianic subjects.

Not only was the country riven, first by religious conflict and later Jacobitism, but the departure of court and parliament to London removed potential sources of support and patronage.

The traditionally Calvinistic outlook of the Scottish middle class in the Victorian era, which frowned upon public entertainments in pursuit of pleasure and promoted thrift, not ostentation, may also have inhibited the kind of municipal patronage which enabled opera's transition from a predominantly aristocratic art form to one increasingly patronised by the bourgeoisie in 19th-century Europe.

Two main composers stand out in the 19th century, and early twentieth – the first being Hamish MacCunn who wrote Jeanie Deans in 1894, commissioned by Carl Rosa.

His Scottish based works include The Martyrdom of St Magnus, a chamber opera, and The Lighthouse (about the Flannan Isles incident).

Non-Scottish based operas by Davies include Mr Emmet Takes a Walk, Kommilitonen!, The Doctor of Myddfai, Cinderella and Resurrection.

The "Five:15 Operas Made in Scotland" ran for two seasons, and involved Scots writers as diverse as Ian Rankin and Alexander McCall Smith.

[25] This was followed in 2012 by The Lady from the Sea with a libretto by Zoë Strachan after Ibsen[19][26] More recent operas have tended to be shaped in one act, but the librettists have often been more notable than the composers.

This opera, written in lowlands Scots, toured whisky distilleries across Scotland in 2018, telling a story of a Scottish family of distillers, and a mysterious house guest who turns up in the middle of the night.

Their productions include new Scots translations of Mozart's The Magic Flute and Purcell's Dido and Aeneas by librettist Dr Michael Dempster.

[34] Since 1947 and the foundation of the Edinburgh International Festival, a strong standard of provision from visiting companies has normally formed a highlight of the Scottish operatic year.

After much criticism of the inadequacy of venues, a plan from 1960 to construct a long overdue opera house-concert hall complex developed into a long-running saga that became known as Edinburgh's "hole in the ground".

[36] Subsequently, Festival opera has found its home in large traditional Edinburgh venues, renovated in turn to bring them up to modern standards.