Operation Bertram

The tanks were replaced that same night with dummies in their original positions, so the armour remained seemingly two or more days' journey behind the front line.

To reinforce the impression that the attack was not ready, a dummy water pipeline was constructed, at an apparent rate of 5 mi (8.0 km) per day.

After the battle, the captured German Panzerarmee general Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma told Montgomery that he had believed the Allies had at least one more armoured division than they did and that the attack would be in the south.

Bertram had succeeded; when announcing the victory at El Alamein in the House of Commons, Winston Churchill praised the camouflage operation.

Bertram was devised by Dudley Clarke to deceive Erwin Rommel about the timing and location of the expected allied attack by the Eighth Army.

[4] The front line was relatively short: it stretched from the Mediterranean Sea in the north, near El Alamein railway station, to the effectively impassable Qattara Depression in the south, a distance of only about 30 miles.

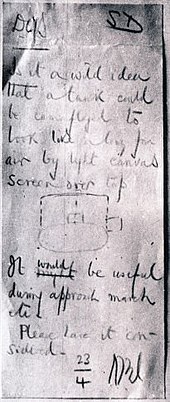

[2][5] Soon after his arrival on 8 August 1942, the new Middle East commander, Harold Alexander, visited Geoffrey Barkas's camouflage unit at Helwan to assess its ability to implement Bertram.

[6] On 16 September 1942, Freddie de Guingand, Montgomery's chief of staff, summoned Barkas and Tony Ayrton to Eighth Army headquarters near Borg-el-Arab.

He introduced Charles Richardson, who worked for Dudley Clarke's secretive 'A' Force and was to implement the deception Montgomery needed.

[7] De Guingand outlined the basic plan: an attack in the north, along the line of the coast road, with a feint some 20 miles to the south.

He then astonished them by asking them to hide the hundreds of tanks and field guns, and the thousands of tons of matériel, that were to be used for the decisive attack at El Alamein.

Barkas recalled the sacked Jasper Maskelyne, a stage magician who had briefly worked for him, saying he needed his vanishing tricks now.

They would give the appearance of not being ready by making it seem the tanks had not moved from their forming-up areas (Murrayfield and Melting Pot).

"[10] Barkas, a former film director, was set to work "on the task of providing props for the biggest 'film production' on which I ever expect to be engaged".

[8] The operation had two aims: creating the appearance of army units where none existed and concealing the real armour, artillery and matériel at the front.

Barkas observed that "the concealment of the huge assembly of the Armoured Corps was essentially a piece of military planning by Army Headquarters, with Camouflage carrying out certain specific tasks".

Brian Robb had arrived more informally: he joined the army as a private, but Barkas noticed him and made use of his skills as an artist, teacher and illustrator by having him speedily promoted to Staff Lieutenant.

One company worked the standard bed frame palm hurdles into the required shapes and fixed them together to make tank bodies, turrets and other dummy vehicle elements.

[17] Different models of Sunshield existed to fit the various types of Allied tank which included Crusaders, Valentines, Grants and Shermans, mimicking different kinds of truck.

They were more simply camouflaged, again as trucks with real wheels, by draping a net over four poles tied to the sides of the vehicle and braced with guy ropes.

In Barkas's own words[22] the great concentration of 25-pounders... seems to have been quite undetectable right up to the instant when its disguise was thrown off and the gunners opened fire.Petrol cans were stacked along the sides of existing revetted trenches near El Alamein railway station.

The tanks were replaced that same night with dummies in their original positions so that the armour remained seemingly two or more days' journey behind the front line.

To reinforce the impression that the attack was not ready, a dummy water pipeline was constructed in "Operation Diamond", at an apparent rate of 5 miles per day.

[28] After the battle, the captured German panzerarmee general Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma told Montgomery that he had believed the allies had at least one more armoured division than they did, and that the attack would be in the south.

[31] On 11 November 1942, Winston Churchill described the battle at El Alamein to the House of Commons, London and praised the success of Operation Bertram:[32] By a marvellous system of camouflage, complete tactical surprise was achieved in the desert.

The Xth Corps, which he had seen from the air exercising fifty miles in the rear, moved silently away in the night, but leaving an exact simulacrum of its tanks where it had been, and proceeded to its points of attack.