Operation Mongoose

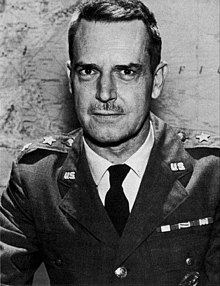

[11][12] The operation was led by United States Air Force General Edward Lansdale on the military side and William King Harvey at the CIA and went into effect after the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion.

[17] The government formally authorized the operation on March 17, 1960, when President Dwight Eisenhower signed off on a CIA paper titled "A Program of Covert Action Against the Castro Regime.

"[18] A declassified report by the Inspector General Lyman Kirkpatrick details the history of the operation, and states that the presidential order gave the agency authorization to create an organization of exiled Cubans to manage opposition programs, begin a "propaganda offensive" to draw support for the movement, create an intelligence gathering network inside Cuba, and to "develop a paramilitary force to be introduced into Cuba to organize, train and lead resistance groups against the Castro regime.

They also aimed to induce the Cuban government to introduce intrusive civil measures to try to prevent the attacks and the concomitant civilian deaths, as well as forcing the diversion of resources to this end.

[13] Following a meeting in the White House on November 3, 1961, this initiative became known as Operation Mongoose and would be led by Air Force Brigadier General Edward Lansdale on the military side and William King Harvey at the CIA.

[23] As the operation's leader, Brigadier General Lansdale received briefings and updates from these agencies and reported directly to a group of high-ranking government officials, known as Special Group-Augmented (SG-A).

The plot against Castro would be characterized by the appearance of a "growing and increasingly effective internal resistance, helped by the activities of defeated Cuban aircraft and by the infiltration of weapons and small groups of men."

"[33] During the planning of Operation Mongoose, a March 1962 CIA memorandum sought a brief but precise description of pretexts which the Joint Chiefs of Staff considered would provide justification for American military intervention in Cuba.

Plans included war crimes directed at civilians such as the use of U.S. Army Special Forces, destruction of Cuban sugar crops by chemical warfare, and mining of harbors.

Some of these plans included the publication of anti-Castro political propaganda, armaments for militant opposition groups, the establishment of guerrilla bases throughout the country, and preparations for an October military intervention in Cuba.

[11][12] Agency activities were also based at the Caribbean Admission Center at Opa-Locka, Florida,[43] and even at one point enlisted the aid of the Mafia (who were eager to regain their Cuban casino operations) to plot an assassination attempt against Castro; William Harvey was one of the CIA case officers who directly dealt with mafioso John Roselli.

[45] Historian Stephen Rabe writes that "scholars have understandably focused on...the Bay of Pigs invasion, the US campaign of terrorism and sabotage known as Operation Mongoose, the assassination plots against Fidel Castro, and, of course, the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Rabe writes that reports from the Church Committee reveal that from June 1963 onward, the Kennedy administration intensified its war against Cuba while the CIA integrated propaganda, economic denial, and sabotage to attack the Cuban state as well as specific targets within.

[5] One example cited is an incident where CIA agents, seeking to assassinate Castro, provided a Cuban official, Rolando Cubela Secades, with a ballpoint pen rigged with a poisonous hypodermic needle.

Rabe further documents how "Exile groups, such as Alpha 66 and the Second Front of Escambray, staged hit-and-run raids on the island... on ships transporting goods…purchased arms in the United States and launched...attacks from the Bahamas.

"[4]: 310–312 However, Noam Chomsky has argued that "terrorist operations continued through the tensest moments of the missile crisis", remarking that "they were formally canceled on October 30, several days after the Kennedy and Khrushchev agreement, but went on nonetheless".

"[46] Operation Mongoose consisted of a program of covert action, including sabotage, psychological warfare, intelligence collection, and the creation of an internal revolution against the communist government.

Two political operations were performed in Phase I: counter Castro-Communist propaganda exploitation of May Day and to arouse strong Hemisphere reaction to Cuban military suppression of the hunger demonstration at Cardenas in June.

The first plan in this time frame involved an attack on the radio station Castro used to "broadcast his speeches with an aerosol spray of a chemical that produced reactions similar to those of lysergic acid (LSD)".

By the summer of 1960, the JMATE, a unit under the direct command of Richard M. Bissell and the DPD, strove to acquire "aircraft for infiltration, propaganda, and supply drops to dissent groups within Cuba."

Conflicting accounts in the Inspector General's report of how later events during this time period played out make it difficult to discern the path of how the Cuba task force handled its operations.

In his 1987 Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis, Raymond L. Garthoff wrote that, "By November 8 the United States had begun perceptibly to stiffen its insistence" on various issues not resolved by the October 28 Kennedy-Khrushchev agreement, "including what the Soviets could only see as an effort to backpedal on what was, for them, the key question remaining: American assurances not to attack Cuba.

Garthoff said that sabotage had been planned before the October 28 agreement and was beyond recall when the Kennedy administration realized it was still in progress, However, "To the Soviets, this was probably seen as a subtle American reminder of its ability to harass and attempt to subvert the Castro regime.

[68] Another attempt at Castro's life was by way of a fountain pen loaded with the poison Black Leaf 40 and passed to a Cuban asset in Paris the day of President Kennedy's assassination, November 22, 1963.

"[75] Further investigation proved that the 1,500 men would not have been enough from the start against Castro's large military forces, as well as Agencies' lack of "top-flight handling," which altogether led to the complete failure of Operation Mongoose as well as the Bay of Pigs invasion.

A memorandum from 15 August 1961 lays out the definitive conclusion of the committee: "The leaders of the operation did not always present their case with sufficient force and clarity to the senior officers of the government to allow the latter to appreciate the consequences of their decisions.

At the end of the fourth volume, Pfeiffer laments that Taylor had a hand in perpetuating the idea that "President Kennedy was a white knight misled by overconfident, if not mischievous, CIA activists."

"[80] Another criticism was the "severe shortage of Spanish language capability among those who were assigned to the task force" throughout its life, and how even when the project employed 600 officials, Director Allen Dulles "never gave proper attention to the personnel situation".

"[80] As previously mentioned, there was the thought from sources close to the investigation that the IG's survey took the form that it did because Kirkpatrick wanted to inherit Bissell's job, should it become vacant - a view Pfeiffer calls "simplistic" but "basically at the heart of the matter".

"[84] In the Oliver Stone film JFK, Operation Mongoose is portrayed in flashback sequences as a training ground where, among others, Lee Harvey Oswald becomes versed in anti-Castro militia tactics.