First Opium War

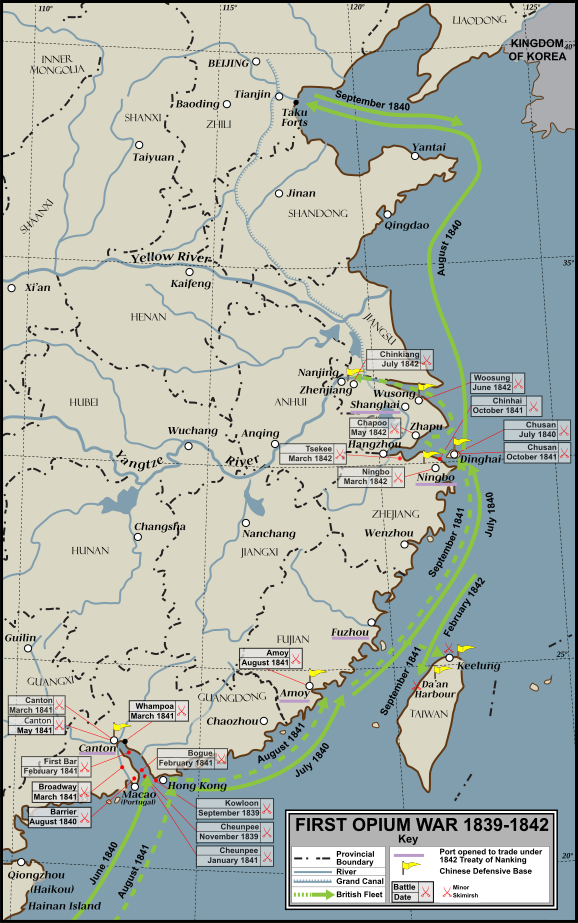

[20] Without establishing formal relations through the Chinese tributary system, by which most Asian nations were able to negotiate with China, British merchants were only allowed to trade at the ports of Zhoushan, Xiamen (or Amoy), and Guangzhou.

Ships did try to call at other ports, but these locations could not match the benefits of Guangzhou's geographic position at the mouth of the Pearl River, nor did they have the city's long experience in balancing the demands of Beijing with those of Chinese and foreign merchants.

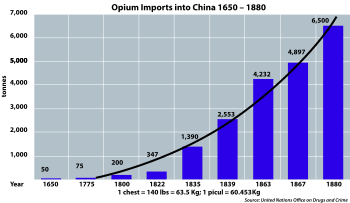

[23] From the system's inception in 1757, trading in China was extremely lucrative for European and Chinese merchants alike as goods such as tea, porcelain, and silk were valued highly enough in Europe to justify the expenses of travelling to Asia.

[25][page range too broad] The Cohong were particularly powerful in the Old China Trade, as they were tasked with appraising the value of foreign products, purchasing or rebuffing said imports and charged with selling Chinese exports at an appropriate price.

[44] European and American ships were able to arrive in Guangzhou with their holds filled with opium, sell their cargo, use the proceeds to buy Chinese goods, and turn a profit in the form of silver bullion.

[25][page range too broad] While opium remained the most profitable good to trade with China, foreign merchants began to export other cargoes, such as machine-spun cotton cloth, rattan, ginseng, fur, clocks, and steel tools.

[42][page range too broad] Efforts by Qing officials to curb opium imports through regulations on consumption resulted in an increase in drug smuggling by European and Chinese traders, and corruption was rampant.

[61][page needed][74] A significant development came in 1834 when reformers (some of whom were financially backed by Jardine)[71] in Britain, advocating for free trade, succeeded in ending the monopoly of the British East India Company under the Charter Act of the previous year.

Later, people of all social strata—from government officials and members of the gentry to craftsmen, merchants, entertainers, and servants, and even women, Buddhist monks and nuns, and Taoist priests—took up the habit and openly bought and equipped themselves with smoking instruments.

Historian Jonathan D. Spence lists these factors that led to war: In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor appointed scholar-official Lin Zexu to the post of Special Imperial Commissioner with the task of eradicating the opium trade.

Fearing that the Chinese would reject any contacts with the British and eventually attack with fire rafts, he ordered all ships to leave Chuenpi and head for Causeway Bay, 20 miles (30 km) from Macau, hoping that offshore anchorages would be out of range of Lin.

The governor refused for fear that the Chinese would discontinue supplying food and other necessities to Macau, and on 14 January 1840 the Daoguang Emperor asked all foreign merchants in China to halt material assistance to the British.

They were to then capture the Zhoushan Islands, blockade the mouth of the Yangtze River, start negotiations with Qing officials, and finally sail the fleet into the Bohai Sea, where they would send another copy of the aforementioned letter to Beijing.

In terms of naval forces, the ships earmarked for the expedition were either posted in remote colonies or under repair, and Oriental Crisis of 1840 (and the resulting risk of war between Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire over Syria) drew the attention of the Royal Navy's European fleets away from China.

Bremer judged that gaining control of the Pearl River and Guangzhou would put the British in a strong negotiating position with the Qing authorities, as well as allow for the renewal of trade when the war ended.

[141][better source needed] Knowing the strategic value of Pearl River Delta to China and aware that British naval superiority made a reconquest of the region unlikely, Qishan attempted to prevent the war from widening further by negotiating a peace treaty with Britain.

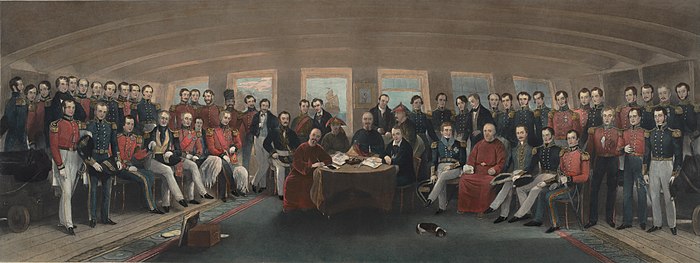

[142][143] The convention would establish equal diplomatic rights between Britain and China, exchange Hong Kong Island for Zhoushan, facilitate the release of shipwrecked and kidnapped British citizens held by the Chinese, and reopen trade in Guangzhou by 1 February 1841.

Chinese military engineers began to establish a number of mud earthworks on the riverbank, sank junks to create blockships on the river, and started constructing fire rafts and gunboats.

[154] During the build-up, the Qing army was weakened by infighting between units and lack of confidence in Yishan, who openly distrusted Cantonese civilians and soldiers, instead choosing to rely on forces drawn from other Chinese provinces.

[101][page needed] On 20 May, Yishan issued a statement, asking the "people of Canton, and all foreign merchants who are respectfully obedient, not to tremble with alarm and be frightened out of their wits at the military hosts that are gathering around, there being no probability of hostilities."

Pottinger wanted to negotiate terms with the Qing for the entire country of China, rather than just the Pearl River, and so he turned away Chinese envoys from Guangzhou and gave permission for the expeditionary force to proceed with its war plans.

Admiral William Parker, 1st Baronet of Shenstone also arrived in Hong Kong to replace Humphrey Fleming Senhouse (who had died of a fever on 29 June) as the commander of the British naval forces in China.

[186][78][page needed][182] After capturing Zhenjiang, the British fleet cut the vital Grand Canal, paralysing the Caoyun system and severely disrupting the Chinese ability to distribute grain throughout the Empire.

In an 1842 edict he said: ... the invasion by the rebellious barbarians, they depended upon their strong ships and effective guns to commit outrageous acts on the seas and harm our people, largely because the native war junks are too small to match them.

The Chinese blend of gunpowder also contained more charcoal than the British mixture did;[citation needed] while this made it more stable and thus easier to store, it also limited its potential as a propellant, decreasing projectile range and accuracy.

[214][failed verification] A British officer said of the opposing Qing forces, "The Chinese are robust muscular fellows, and no cowards; the Tartars [i.e. Manchus] desperate; but neither are well commanded nor acquainted with European warfare.

On the one side was a corrupt, decadent and caste-ridden despotism, with no desire or ability to wage war, which relied on custom much more than force for the enforcement of extreme privilege and discrimination, and which was blinded by a deep-rooted superiority complex into believing that they could assert their supremacy over Europeans without possessing military power.

They argued that Palmerston (the foreign secretary) was only interested in the huge profits it would bring Britain, and was totally oblivious to the horrible moral evils of opium which the Chinese government was valiantly trying to stamp out.

[124][page range too broad] Former American president John Quincy Adams commented that opium was "a mere incident to the dispute ... the cause of the war is the kowtow—the arrogant and insupportable pretensions of China that she will hold commercial intercourse with the rest of mankind not upon terms of equal reciprocity, but upon the insulting and degrading forms of the relations between lord and vassal.

[267] It was not economics, opium sales or expanding trade that caused the British to go to war, Melancon argues, but it was more a matter of upholding aristocratic standards of national honour sullied by Chinese insults.