Optical telescope

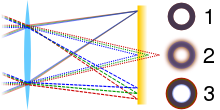

There are three primary types of optical telescope : An optical telescope's ability to resolve small details is directly related to the diameter (or aperture) of its objective (the primary lens or mirror that collects and focuses the light), and its light-gathering power is related to the area of the objective.

[1][2] The lens and the properties of refracting and reflecting light had been known since antiquity, and theory on how they worked was developed by ancient Greek philosophers, preserved and expanded on in the medieval Islamic world, and had reached a significantly advanced state by the time of the telescope's invention in early modern Europe.

[7] It is in the Netherlands in 1608 where the first documents describing a refracting optical telescope surfaced in the form of a patent filed by spectacle maker Hans Lippershey, followed a few weeks later by claims by Jacob Metius, and a third unknown applicant, that they also knew of this "art".

[8] Word of the invention spread fast and Galileo Galilei, on hearing of the device, was making his own improved designs within a year and was the first to publish astronomical results using a telescope.

The next big step in the development of refractors was the advent of the Achromatic lens in the early 18th century,[11] which corrected the chromatic aberration in Keplerian telescopes up to that time—allowing for much shorter instruments with much larger objectives.

[citation needed] For reflecting telescopes, which use a curved mirror in place of the objective lens, theory preceded practice.

The theoretical basis for curved mirrors behaving similar to lenses was probably established by Alhazen, whose theories had been widely disseminated in Latin translations of his work.

A mid-20th century innovation was catadioptric telescopes such as the Schmidt camera, which uses both a lens (corrector plate) and mirror as primary optical elements, mainly used for wide field imaging without spherical aberration.

[citation needed] The late 20th century has seen the development of adaptive optics and space telescopes to overcome the problems of astronomical seeing.

[citation needed] The electronics revolution of the early 21st century led to the development of computer-connected telescopes in the 2010s that allow non-professional skywatchers to observe stars and satellites using relatively low-cost equipment by taking advantage of digital astrophotographic techniques developed by professional astronomers over previous decades.

However, a mirror diagonal is often used to place the eyepiece in a more convenient viewing location, and in that case the image is erect, but still reversed left to right.

These may be integral part of the optical design (Newtonian telescope, Cassegrain reflector or similar types), or may simply be used to place the eyepiece or detector at a more convenient position.

It is analogous to angular resolution, but differs in definition: instead of separation ability between point-light sources it refers to the physical area that can be resolved.

This limit can be overcome by placing the telescopes above the atmosphere, e.g., on the summits of high mountains, on balloons and high-flying airplanes, or in space.

Faster systems often have more optical aberrations away from the center of the field of view and are generally more demanding of eyepiece designs than slower ones.

A lifetime spent exposed to chronically bright ambient light, such as sunlight reflected off of open fields of snow, or white-sand beaches, or cement, will tend to make individuals' pupils permanently smaller.

Sunglasses greatly help, but once shrunk by long-time over-exposure to bright light, even the use of opthamalogic drugs cannot restore lost pupil size.

[24] Most observers' eyes instantly respond to darkness by widening the pupil to almost its maximum, although complete adaption to night vision generally takes at least a half-hour.

An eyepiece of the same apparent field-of-view but longer focal-length will deliver a wider true field of view, but dimmer image.

A physical limit derives from the combination where the FOV cannot be viewed larger than a defined maximum, due to diffraction of the optics.

As the eyepiece has a larger focal length than the minimum magnification, an abundance of wasted light is not received through the eyes.

The limit to the increase in surface brightness as one reduces magnification is the exit pupil: a cylinder of light that projects out the eyepiece to the observer.

So if the focal length is measured in millimeters, the image scale is The derivation of this equation is fairly straightforward and the result is the same for reflecting or refracting telescopes.

Many types have been constructed over the years depending on the optical technology, such as refracting and reflecting, the nature of the light or object being imaged, and even where they are placed, such as space telescopes.

Some reasons are: Most large research reflectors operate at different focal planes, depending on the type and size of the instrument being used.

In this generation of telescopes, the mirror is usually very thin, and is kept in an optimal shape by an array of actuators (see active optics).

Relatively cheap, mass-produced ~2 meter telescopes have recently been developed and have made a significant impact on astronomy research.

After the photographic plate, successive generations of electronic detectors, such as the charge-coupled device (CCDs), have been perfected, each with more sensitivity and resolution, and often with a wider wavelength coverage.

At this point, if greater resolution is needed at that wavelength, a wider mirror has to be built or aperture synthesis performed using an array of nearby telescopes.

In recent years, a number of technologies to overcome the distortions caused by atmosphere on ground-based telescopes have been developed, with good results.