Oral gospel traditions

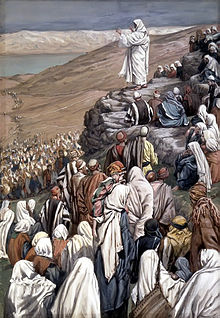

It is widely agreed amongst Biblical scholars that accounts of Jesus's teachings and life were initially conserved by oral transmission, which was the source of the written gospels.

[3] For much of the 20th Century, form criticism, pioneered by figures such as Martin Dibelius and Rudolf Bultmann, dominated Biblical scholarship.

Gerhardsson, basing his research off of Rabbinic methods of transmission, argued that the early Christians transmitted the story and teachings of Jesus through strict memorization, claiming that a collegium formed by the twelve disciples could carefully control tradition.

[6] Indeed, Kelber's groundbreaking works caused what Theodore Weeden called "a paradigmatic crisis" that would reshape scholarship in the years to come.

[7] Kenneth Bailey was another scholar who made a tremendous mark on par with Kelber on the study of the Oral Gospel Traditions.

Bailey argued that communities, especially by leading members, informally controlled oral traditions to a degree, preventing core parts of stories from major change.

[10] The essence of form criticism is the identification of the Sitz im Leben, "situation in life", which gave rise to a particular written passage.

[13] According to scholar Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus was so very firmly rooted in his own time and place as a first-century Palestinian Jew – with his ancient Jewish comprehension of the world and God – that he does not translate easily into a modern idiom.

"[16] NT Wright also argued for a stable oral tradition, stating "Communities that live in an oral culture tend to be story-telling communities [...] Such stories [...] acquire a fairly fixed form, down to precise phraseology [...] they retain that form, and phraseology, as long as they are told [...] The storyteller in such a culture has no license to invent or adapt at will.

[17] According to Anthony Le Donne, "Oral cultures have been capable of tremendous competence...The oral culture in which Jesus was reared trained their brightest children to remember entire libraries of story, law, poetry, song, etcetera...When a rabbi imparted something important to his disciples, the memory was expected to maintain a high degree of stability."

[19] According to Dunn, one of the most striking features to emerge from his study is the "amazing consistency" of the history of the tradition "which gave birth to the NT".

[22] Rafael Rodriguez also sees Kelber's media contrast as much too distinct, arguing that tradition was sustained in memory alongside text.

[25] Travis Derico, following Dunn's ideas, argues that memorization and oral transmission can potentially account for the Synoptics instead and deserves increased study.

Ehrman also overemphasizes individual transmission instead of community, makes a 'lethal oversight' where Jan Vansina, whom he quoted as evidence for corruption in the Jesus tradition, changed his mind, arguing that information was conveyed through a community that placed controls, rather than through chains of transmission easily subject to change.

According to Maurice Casey, Aramaic sources have been detected in Mark's Gospel, which could indicate use of early or even eyewitness testimony when it was being written.