Jesus in comparative mythology

Though the relationship between the two religions is still under dispute, Christian apologists at the time noted similarities between them, which some scholars have taken as evidence of borrowing, but which are more likely a result of shared cultural environment.

[13][14][38] Brennan R. Hill states that Jesus's miracles are, for the most part, clearly told in the context of the Jewish belief in the healing power of Yahweh,[14] but notes that the authors of the Synoptic Gospels may have subtly borrowed from Greek literary models.

[40] Scholars disagree whether the parable of the rich man and Lazarus recorded in Luke 16:19–31 originates with Jesus or if it is a later Christian invention,[41] but the story bears strong resemblances to various folktales told throughout the Near East.

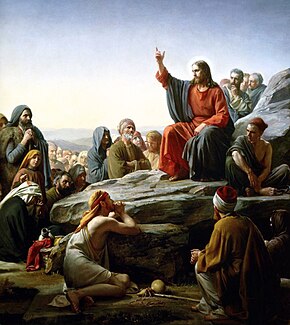

[48][49][50][nb 12] In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus delivers his first public sermon on a mountain in imitation of the giving of the Law of Moses atop Mount Sinai.

[57] Most secular historians therefore generally see the two separate accounts of the virgin birth from the Gospels of Matthew and Luke as independent legendary inventions designed to fulfill the mistranslated passage from Isaiah.

[64] The German historian of religion Martin Hengel notes that the Hellenized Syrian satirist Lucian of Samosata ("the Voltaire of antiquity"), in his comic dialogue Prometheus, written in the second century AD (about two hundred years after Jesus), describes the god Prometheus being fastened to two rocks in the Caucasus Mountains using all the terminology of a Roman crucifixion:[63] he is nailed through the hands in such a manner as to produce "a most serviceable cross" ("ἐπικαιρότατος... ὁ σταυρος").

[64] American theologian Dennis R. MacDonald has argued that the Gospel of Mark is, in fact, a Jewish retelling of the Odyssey, with its ending derived from the Iliad, that uses Jesus as its central character in the place of Odysseus.

[65] MacDonald's thesis that the gospels are modelled on the Homeric Epics has been met with intense scepticism in scholarly circles due to its almost complete reliance on extremely vague and subjective parallels.

[90] Mark W. G. Stibbe has argued that the Gospel of John also contains parallels with The Bacchae, a tragedy written by the Athenian playwright Euripides that was first performed in 405 BC and involves Dionysus as a central character.

[91][94] Both works end with the violent death of one of the central figures;[94] in John's gospel it is Jesus himself, but in The Bacchae it is Dionysus's cousin and adversary Pentheus, the king of Thebes.

[98] One of the most obvious differences is that, in The Bacchae, Dionysus has come to advocate a philosophy of wine and hedonism;[98] whereas Jesus in the Gospel of John has come to offer his followers salvation from sin.

[113] Christianity and Mithraism were both of Oriental origin[114] and their practices and respective saviour figures were both shaped by the social conditions in the Roman Empire during the time period.

[121] In Mithraic cults primarily from the Rhine-Danube region, there are also representations of a myth in which Mithras shoots an arrow at a rock face, causing water to gush forth.

[124][108] The exact interpretation of this scene is unclear,[108] but the image certainly depicts a narrative central to Mithraism[107][109][108] and the figures in it appear to correspond to the signs of the zodiac.

"[130] The later apologist Tertullian writes in his De praescriptione haereticorum: The devil (is the inspirer of the heretics) whose work it is to pervert the truth, who with idolatrous mysteries endeavours to imitate the realities of the divine sacraments.

Some he himself sprinkles as though in token of faith and loyalty; he promises forgiveness of sins through baptism; and if my memory does not fail me marks his own soldiers with the sign of Mithra on their foreheads, commemorates an offering of bread, introduces a mock resurrection, and with the sword opens the way to the crown.

[142] One unusual possible instance of identification between Jesus and Orpheus is a hematite gem inscribed with the image of a crucified man identified as ΟΡΦΕΩΣ ΒΑΚΧΙΚΟΣ (Orpheos Bacchikos).

[156] The Church Father Jerome records in a letter dated to the year 395 AD that "Bethlehem... belonging now to us... was overshadowed by a grove of Tammuz, that is to say, Adonis, and in the cave where once the infant Christ cried, the lover of Venus was lamented.

[157] Joan E. Taylor has countered this argument by arguing that Jerome, as an educated man, could not have been so naïve as to mistake Christian mourning over the Massacre of the Innocents as a pagan ritual for Tammuz.

[166][167] Maurice Casey, the late Emeritus Professor of New Testament Languages and Literature at the University of Nottingham, writes that these parallels do not in any way indicate that Jesus was invented based on pagan "divine men",[168] but rather that he was simply not as perfectly unique as many evangelical Christians frequently claim he was.

[169][176] According to this account, Hephaestus, the god of blacksmiths, once attempted to rape Athena, the virgin goddess of wisdom, but she pushed him away, causing him to ejaculate on her thigh.

[189] According to M. David Litwa, the authors of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke consciously attempt to avoid portraying Jesus's conception as anything resembling pagan accounts of divine parentage;[190] the author of the Gospel of Luke tells a similar story about the conception of John the Baptist in effort to emphasize the Jewish character of Jesus's birth.

[192] The third-century AD Christian theologian Origen retells a legend that Plato's mother Perictione had virginally conceived him after the god Apollo had appeared to her husband Ariston and told him not to consummate his marriage with his wife,[180][193][194] a scene closely paralleling the account of the Annunciation to Joseph from the Gospel of Matthew.

[180][195] In the fourth century, the bishop Epiphanius of Salamis protested that, in Alexandria, at the temple of Kore-Persephone, the pagans enacted a "hideous mockery" of the Christian Epiphany in which they claimed that "Today at this hour Kore, that is the virgin, has given birth to Aion.

"[180] Folklorist Alan Dundes has argued that Jesus fits all but five of the twenty-two narrative patterns in the Rank-Raglan mythotype,[196][197] and therefore more closely matches the archetype than many of the heroes traditionally cited to support it, such as Jason, Bellerophon, Pelops, Asclepius, Joseph, Elijah, and Siegfried.

[198][197] Dundes sees Jesus as a historical "miracle-worker" or "religious teacher", accounts of whose life were told and retold through oral tradition so many times that they became legend.

[203] Nonetheless, Lawrence M. Wills states that the "hero paradigm in some form does apply to the earliest lives of Jesus", albeit not to the extreme extent that Dundes has argued.

[202] The late nineteenth-century Scottish anthropologist Sir James George Frazer wrote extensively about the existence of a "dying-and rising god" archetype in his monumental study of comparative religion The Golden Bough (the first edition of which was published in 1890)[204][207] as well as in later works.

[217][219] Frazer and others also saw Tammuz's Greek equivalent Adonis as a "dying-and-rising god",[205][204][220] despite the fact that he is never described as rising from the dead in any extant Greco-Roman writings[221] and the only possible allusions to his supposed resurrection come from late, highly ambiguous statements made by Christian authors.

[208][219][226] In 1987, Jonathan Z. Smith concluded in Mircea Eliade's Encyclopedia of Religion that "The category of dying and rising gods, once a major topic of scholarly investigation, must now be understood to have been largely a misnomer based on imaginative reconstructions and exceedingly late or highly ambiguous texts.