Origins of agriculture in West Asia

The beginnings of agriculture in the Near East can be traced back to the early Neolithic period, between 10,000 and 8,000 BC, when a series of domestications by human communities took place, primarily involving a few plants (cereals and legumes) and animals (sheep, goats, bos, and pigs).

[11] From an economic, social and cultural point of view, the study of the phenomenon was marked by the work of Vere Gordon Childe, who in the 1920s and 1930s introduced his concept of the “Neolithic revolution”, which characterized the beginning of agriculture.

[17] This has been referred to as the “Fertile Crescent”, a concept that originated in the work of James Henry Breasted, and which in its current sense is a biogeographical area that extends roughly over the Levant and the slopes and foothills of the Taurus and Zagros.

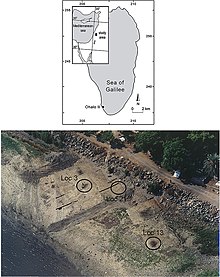

[18] The Levant, located to the east of the eastern Mediterranean, is characterized by alternating environments stretching in a north-south direction: the coastal plain to the west, which was wider during the Epipaleolithic and Neolithic periods than it is today, since sea levels were lower, then progressing eastwards, the foothills gradually rise to form mountain ranges, often well-forested and reaching up to 2,000 meters in altitude, then a new low-lying zone, the Rift or “Levantine corridor”, a structuring axis that descends to the south below sea level, followed by an area of higher plateaus and, finally, a slow descent towards the Arabian desert.

However, this period cannot be summed up simply as a gradual warming, as the climate underwent several fluctuations during the Epipaleolithic and Neolithic phases: These variations in temperature and precipitation had a significant impact on natural environments.

[41] In the regions of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia, it is variations in precipitation, especially concentrated in winter and which can be very large from one year to the next under current conditions, have had a greater impact on human societies than fluctuations in temperature.

[37] It is generally accepted that 200 mm of annual precipitation are needed for agriculture without artificial water input (“dry”), but in areas at the junction of arid zones, this limit may be exceeded one year and not reached the next.

[53] We also observe the sex and age of slaughtered animals, determined by the bones, provided they are sufficiently complete:[54] a domestic herd will tend to have more adult females than males (sex-ratio analysis), to have more female breeders, whereas in the wild the proportions are equivalent; if we rely on modern practices, a farm intended to produce meat will tend to slaughter above all young adult males, which are not normally the individuals with the highest mortality in the wild and whose high mortality is likely to jeopardize the renewal of the herd.

The preludes to plant and animal domestication occur during the final period of the Upper Paleolithic: the Epipaleolithic, at the end of which (c. 12500-11000 BC) human groups are hunter-gatherers who begin to settle.

They consumed the same types of plants and animals: cereals and other grasses, legumes, pistachios; large game for the most part (gazelle dominant in the Levant, fallow deer, wild boar, auroch, hemione, etc.)

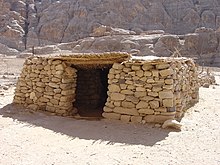

It is undoubtedly based on a form of cultivation practiced on plots of land, mixing and alternating several plants, complemented by small-scale livestock farming providing valuable food supplements.

More generally, some scholars have claimed that no explanations are likely to be universally applicable, whereas others have adopted an explicitly comparative approach, identifying parallel processes and exploring common underlying patterns.

[122]Many traditional explanations take into account only one main and determining factor to explain the changes leading to the adoption of agriculture (an “unmoved mover”): climate, environment, demography, social competition, etc.

Milk may also have been consumed, and we must not rule out the possibility that animal “by-products” played a role from the outset: sheep wool and goat hair may have been used extensively as early as the Neolithic, and dung may have been used as fertilizer.

O. Bar-Yosef considers that certain Natoufian communities faced with the cooling of the Recent Dryas would have sought to intensify the exploitation of their ecological niche, taking advantage of all possible options, including agriculture, which would have led to domestication over the long term.

The scenarios most representative of this idea are L. Binford's “equilibrium model” and K. Flannery's “broad spectrum revolution”: communities with a growing population must share constant food resources between a greater number of individuals, and obtain them from a smaller area.

[143] Others criticize these proposals because, in their view, there is no clear evidence that the pre-Neolithic world was “full”, that hunter-gatherers of the time exploited the potential of their environments to the maximum, and exceeded their “carrying capacity”.

[147] Early proposed explanations for Neolithization were based on the premise that the first farmers must have learned how plant germination worked to start farming, and that they developed more efficient tools than those of earlier phases.

[138] Among the most influential works on the cultural and religious approach, those of J. Cauvin derive Neolithization from a “revolution of symbols” occurring at the beginning of the PPNA (Khiamian), which leads him to reject any materialistic explanation and proposes that the origin of agriculture should be sought as the “inauguration of a new behavior of sedentary communities about their natural environment” and of animal husbandry as the product of “a human desire to dominate beasts”.

They have developed and passed on a whole body of knowledge about crops and livestock (soil management and tillage, farming tools, artificial watering, selection of individuals, castration of animals, etc.).

In addition, the shift to an agricultural economy seems to have increased the workload: tilling the fields, watching over the herds and milling the grain requires many hours of labor divided between all members of the community.

Before this, even in the most arid areas, it was always possible to take advantage of sites with a better water supply: fields were undoubtedly set up on the terraces and alluvial fans of valleys to protect them from flooding, or near non-perennial watercourses or lakes.

What's more, mobility is an integral part of these farmers' strategies: if need be, it enables them to cope with soil exhaustion, dwindling local resourcesm and problems of access to water.

[188] This, too, was a major change in the economy of late Neolithic and Chalcolithic societies, since it required more investment than the cultivation of cereals and legumes (trees and shrubs had to be maintained regularly and were only productive several years after planting).

In addition, and of paramount importance, social “domestication” with new ways of shaping community identity and interaction, whose very essence changed; these ranged from bonding through kinship, exchange networks, craft specialization, feasting, etc., to rivalry, political boundaries and intra- and inter-community conflictual violence.

The causes seem to be the increased availability of cereals and legumes thanks to agriculture, shorter birth intervals due to sedentarization, and a reduction in energy expenditure compared to the old way of life.

Today all urban, sedentary‚ and socially stratified societies are dependent on agricultural surpluses grown by farmers for their ultimate wealth, and these resources all derive from the ancient village way of life.

[203]It has also been argued that the transition from hunter-gatherer to farmer is not advantageous overall: food is less varied, habitats more densely populated, the constraints posed by droughts and epidemics greater, new diseases appear, social inequalities widen and agricultural work is more tedious than hunting and gathering.

Diffusion extended even further; according to G. Willcox:[212]In the Near East, the establishment of mixed farming based on wheat, barley, pulses, and herding of sheep, goat, cattle, and pigs was particularly productive and as a result spread rapidly to Europe and Central Asia.

[216] The coincidence of the emergence of these different domestications, without any direct link between them, throughout five millennia, which is compared to the 300,000 years of Homo sapiens, can no doubt be explained in part by the evolution of human psychic capacities, and undoubtedly by the change in environmental conditions on a global scale following the end of the last Ice Age.