Ottoman reconquest of the Morea

During the conflict, Venetian troops seized the island of Cephalonia (Santa Maura) and the Morea peninsula, although they failed to retake Crete and expand their possessions in the Aegean Sea.

After the end of the Russo-Turkish war, the emboldened Ottoman leadership, under the new Grand Vizier, Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha, turned its attention to reversing the losses of Karlowitz.

Profiting from the general war weariness that made any intervention by the other European powers unlikely, the Porte turned its focus on Venice.

[5][6][7] The inability of the Venetians to effectively defend the Morea had been apparent already during the latter stages of the Great Turkish War, when the Greek renegade Limberakis Gerakaris had launched dangerous raids into the peninsula.

[8] The Republic was well aware of the Ottoman ambitions to recover the Morea, both for reasons of prestige and because of the potential threat to the Ottoman possessions in the rest of Greece posed by Venetian possession of the peninsula: with the Morea as a springboard, the Venetians might seek to reclaim Crete, or foment anti-Ottoman rebellions in the Balkans.

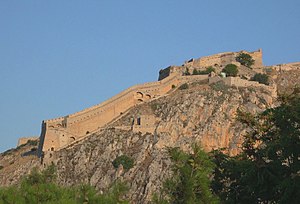

However, the Venetians' position was hampered by problems of supplies and morale, as well as the extreme lack of troops available: in 1702, the garrison at the Acrocorinth, which covered the Isthmus of Corinth, the main invasion route from the mainland, numbered only 2,045 infantry and barely a thousand cavalry.

[11] The Venetian militia (cernide) system was problematic as well, being plagued by money shortages and the reluctance of the colonial subjects to serve in it.

The quality of both the men and their horses was judged as extremely poor, and peacetime losses through desertion or disease meant that they were never at full strength.

[19] According to a contemporary register preserved in Montreal, the total strength of Venetian regular troops in the Morea was 4,414 men:[20][a] Apostolos Vakalopoulos gives similar, but slightly different numbers: 1747 (397 cavalry) at Nauplia, 450 at Corinth, 466 infantry and 491 at Rio and its region, 279 at Monemvasia, 43 each at Kelefa and Zarnata, 719 (245 cavalry) at Coron and Modon, and 179 infantry and 125 at Navarino, for a total of 4,527 men.

[26][27] Even after the arrival of these auxiliary squadrons, in July 1715 Dolfin only possessed 22 ships of the line, 33 galleys, 2 galleasses and 10 galliots, and was at a considerable disadvantage against the Ottoman fleet, which forced him to maintain a rather passive stance.

[34] During the early months of 1715, the Ottomans assembled their army in Macedonia under the Grand Vizier Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha.

[8][27][39] The Ottoman view on the campaign is known mostly through two eyewitness accounts, the diary of the French embassy interpreter Benjamin Brue (published as Journal de la campagne que le Grand Vesir Ali Pacha a faite en 1715 pour la conquête de la Morée, Paris 1870), and that of Constantine the "Dioiketes", a guard officer to the Prince of Wallachia (published by Nicolae Iorga in Chronique de l’expédition des Turcs en Morée 1715 attribuée à Constantin Dioikétès, Bucarest 1913).

[41] "Sent by the state to guard the land,(Which, wrested from the Moslem's hand,While Sobieski tamed his prideBy Buda's wall and Danube's side,The chiefs of Venice wrung awayFrom Patra to Euboea's bay,)Minotti held in Corinth's towersThe Doge's delegated powers,While yet the pitying eye of PeaceSmiled o'er her long forgotten Greece:" According to a report by Minotto, the Ottoman advance guard entered the Morea on 13 June.

With ample stores, a garrison of about 3,000 men, and an artillery complement of at least 150 guns, the city was expected to hold for at least three months, allowing for the arrival of reinforcements over the sea.

[46] The Ottomans then advanced to the southwest, where the forts of Navarino and Koroni were abandoned by the Venetians, who gathered their remaining forces at Methoni (Modon).

However, being denied effective support from the sea by Delfin's reluctance to endanger his fleet by engaging the Ottoman navy, the fort capitulated.

Despite the presence of sufficient material, the Venetian garrisons were weak, and the Venetian government unable to finance the war, while the Ottomans not only enjoyed a considerable numerical superiority, but also were more willing "to tolerate large losses and considerable desertion": according to Brue, no less than 8,000 Ottoman soldiers were killed and another 6,000 wounded in the just nine days of the siege of Nauplia.

The troops received six months' worth of pay on 17 October near Larissa, and the Grand Vizier returned to the capital, for a triumphal entrance, on 2 December.