Ottoman architectural decoration

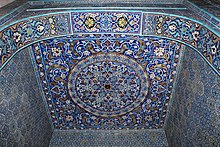

Until the classical period (16th–17th centuries), three-dimensional muqarnas or "stalactite" decoration was the most prominent motif used in entrance portals, niches, columns capitals, and under minaret balconies.

[5] Inscriptions in the mosque record that the decoration was completed in 1424 by Nakkaş Ali, a craftsman native to Bursa who had been transported to Samarkand by Timur after the Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Ankara in 1402.

Tabriz was historically a major center of ceramic art in the Islamic world, and its artists appear to have emigrated and worked in many regions from Central Asia to Egypt.

[7][9] Doğan Kuban argues that the decoration of the Green Mosque complex was more generally a product of collaboration between craftsmen of different regions, as this was the practice in Anatolian Islamic art and architecture during the preceding centuries.

[11] Tilework panels with similar techniques and motifs are found in the courtyard of the Üç Şerefeli Mosque, another building commissioned by Murad II in Edirne, completed in 1437.

[12][13] The evidence from this tilework in Bursa and Edirne indicates the existence of a group or a school of craftsmen, the "Masters of Tabriz", who worked for imperial workshops in the first half of the 15th century and were familiar with both cuerda seca and underglaze techniques.

[7] In the late 15th century, in the 1470s or 1480s, the Iznik industry had grown in prominence and patronage and began producing a new "blue-and-white" fritware which adapted and incorporated Chinese motifs in its decoration.

[27] The Hadim Ibrahim Pasha Mosque (1551) also contains panels of well-executed tiles featuring calligraphic and floral decoration in cobalt blue, white, olive green, turquoise, and pale manganese purple.

[57][59] Tekfursaray tiles are also found in the Hekimoğlu Ali Pasha Mosque (1734), on the Ahmed III Fountain (1729) near Hagia Sophia, and in some of the rooms and corridors of the Harem section in Topkapı Palace.

[60] After the Patrona Halil rebellion in 1730, which deposed Ahmet III and executed his grand vizier, the Tekfursaray kilns were left without a patron and quickly ceased to function.

[62] A moderately successful effort to revive Ottoman tile production occurred under Abdülhamid II in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, partly under the influence of the First National Architectural Movement.

The design of the ornamentation was often stenciled onto the plaster first, using paper pierced with pin holes in the shape of the motifs, over which coal dust was rubbed to leave outlines on the walls that were then painted.

[73] Early Ottoman decorative motifs remained similar to those found in earlier Anatolian Seljuk architecture and in neighboring Islamic cultures, as attested by a few surviving examples from the 15th century.

The ornamentation inside the southeastern (qibla) iwan depicts natural landscapes with stylized flowers and trees that appear to reflect the same artistic styles used in book illustrations and miniatures, particularly those from the Timurid Empire further east.

[75][76] Another floriate style that appeared in Ottoman decoration from the 15th century onward is hatayî,[c] which consists in large part of peonies and leaves shown in varying stages of budding and blooming.

[73] One of the finest examples of this style surviving from the 16th century is found in the Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque (circa 1581), where it is painted on oil cloth stretched over the lower part of the wooden muezzin's gallery.

[79] The verses written in the central medallion were often selected from the an-Nur ("Light") chapter of the Qur'an and may have symbolically imparted a celestial or heavenly connotation to Ottoman domes.

[83] A well-preserved example of the latter is found in the dome of the Chamber of Murad III in Topkapı Palace (circa 1578), consisting of gold rumî scrollwork over a red background.

Instead, it appears on some smaller architectural elements typically seen at close quarters,[86] such as wooden cupboards and window shutters found in the Chamber of Murad III in Topkapı Palace.

[87] The present-day painted decoration inside the domes of many mosques of the era, including the Süleymaniye in Istanbul and the Selimiye in Edirne, dates from restorations in much later centuries.

[88][89] In the Süleymaniye Mosque – whose dome had to be repaired following its collapse in the 1766 earthquake[90] – the original decoration was described by 16th-century writer Ramazanzade Mehmed as featuring many "sun-like disks" and medallion designs in gold and silver.

[93] Another example is the painted wood under the galleries of the Atik Valide Mosque in Üsküdar (circa 1583), which features a geometric pattern of polygons filled with floral motifs.

The reign of Ahmet III (r. 1703–1730), which include the years of the Tulip Period (1718–1730), saw the popularization of a style featuring plentiful depictions of flowers in vases and bowls of fruit, sometimes with shading.

The style was also popular beyond the capital and can be found as far as Crimea, where the palace of the Crimean khan (an Ottoman vassal) in Bakhchisaray contains wooden panels painted in the same manner.

[108] Recent restoration of Abdülhamid I's Tomb (1775–1780) has also managed to recover some of the original paintwork under layers of later repainting, revealing Rococo motifs in shades of green and pink.

[111] Although some minor details of earlier paintwork were suggestive of this technique (e.g. in the Ayazma Mosque), its effective use only began during the reign of Abdülmecid I (r. 1839–1861), when specialists in this type of painting were most likely hired for the purpose.

[119] Nonetheless, high-quality stone carving was still used to enrich the details of buildings throughout the Ottoman period, particularly for entrance portals, minaret balconies, niches, column capitals, and moldings.

The decoration of tombstones included vegetal and floral motifs, stone caps in the shape of headgear reflecting the social status of the deceased (usually for men), and, most consistently of all, inscriptions in graceful calligraphy.

[127] The Nuruosmaniye Mosque (1748–1755) helped to establish a new style of column capital for this era: shaped like an inverse bell, either plain or covered with fluting or other carved details, and often with volutes at its upper corners.

[131] The inner and lateral gates of the Nuruosmaniye are marked by unique designs: they are topped by semi-vaults which are carved with rows of various moldings and acanthus friezes that replace the traditional muqarnas.