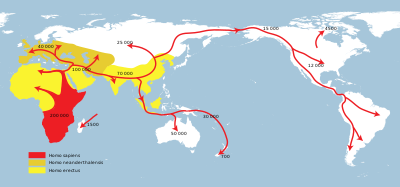

Early expansions of hominins out of Africa

A 2018 study claims hominin presence at Shangchen, central China, as early as 2.12 Ma based on magnetostratigraphic dating of the lowest layer containing stone artefacts.

[4][5] Pre-Homo hominin expansion out of Africa is suggested by the presence of Graecopithecus and Ouranopithecus, found in Greece and Anatolia and dated to c. 8 million years ago, but these are probably Homininae but not Hominini.

The delineation of the "human" genus, Homo, from Australopithecus is somewhat contentious, for which reason the superordinate term "hominin" is often used to include both.

"Hominin" technically includes chimpanzees as well as pre-human species as old as 10 million years old (the separation of Homininae into Hominini and Gorillini).

A 2018 study claims evidence for human presence at Shangchen, central China, as early as 2.12 Ma based on magnetostratigraphic dating of the lowest layer containing stone artefacts.

On the basis of this classification, H. floresiensis is hypothesized to represent a hitherto unknown and very early migration out of Africa, dating to before 2.1 million years ago.

[12] The oldest Homo erectus fossils appear almost contemporaneously, shortly after two million years ago, both in Africa and in the Caucasus.

The skull shows that this Homo erectus was advanced in age and had lost all but one tooth years before death, and it is perhaps unlikely that this hominid would have survived alone.

The Pannonian plain, situated south-west of the Carpathian Mountains, was apparently characterized by a comparatively warm climate similar to that of the Mediterranean Area, while the climate of the western European paleobiogeographic area was mitigated by Gulf Stream influence and could support the episodic hominin dispersals toward the Iberian Peninsula.

[24] Apparently, the faunal exchanges between southeastern Europe and the Near East and southern Asia were controlled by the complex interaction of such geographic obstacles as the Bosporus and the Manych Strait, the climate barrier from the north of the Greater Caucasus range, and the 41 kyr glacial Milankovitch cycles that repeatedly closed the Bosporus and thus triggered the two-way faunal exchange between southeastern Europe and the Near East, and, apparently, the further westward dispersal of the archaic hominins in Eurasia.

[citation needed] The presence of Lower Paleolithic human remains in Indonesian islands is good evidence for seafaring by Homo erectus late in the Early Pleistocene.

[28] He has reproduced a primitive dirigible (steerable) raft to demonstrate the feasibility of faring across the Lombok Strait on such a device, which he believes to have been done before 850 ka.

Archaic humans in Europe beginning about 0.8 Ma (cleaver-producing Acheulean groups) are classified as a separate, erectus-derived species, known as Homo heidelbergensis.

[30] Genetic research also indicates that a later migration wave of H. sapiens (from .07-.05 Ma) from Africa is responsible for all to most of the ancestry of current non-African populations.

The use by hominins of the Levantine corridor, connecting Egypt via the Sinai peninsula with the Eastern Mediterranean, has been associated to the phenomenon of rising and declining humidity of the desert belt of northern Africa, known as the Sahara pump.

The strait has a major appeal in the study of Eurasian expansion in that it brings East Africa close to Eurasia.

Oldowan grade tools are reported from Perim Island,[38] implying that the strait could have been crossed in the Early Pleistocene, but these finds have yet to be confirmed.

Upon reaching this threshold, individuals may find it easier to gather resources in the poorer yet less exploited peripheral environment than in the preferred habitat.

Homo habilis could have developed some baseline behavioural flexibility prior to its expansion into the peripheries (such as encroaching into the predatory guild[45][46]).

[49][50] With Homo erectus' new environmental flexibility, favourable climate fluxes likely opened it the way to the Levantine corridor, perhaps sporadically, in the Early Pleistocene.

[citation needed] Some papers have argued against this hypothesis, showing that the dispersals of hominins from Africa into Eurasia were asynchronous with those of other land mammals and that the latter was thus unlikely to be the cause of the former.

[57][58] Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen[3] suggest that the success of hominins within Eurasia once out of Africa is in part due to the absence of zoonotic diseases outside their original habitat.

When hominins moved out into drier and colder habitats of higher latitudes, one major limiting factor in population growth was removed.

It has been postulated that this was related to the Oldowan-Acheulean transition, as the development of Acheulean technology signifies a change in human ecology from a passive, scavenging role to that of more active predation.