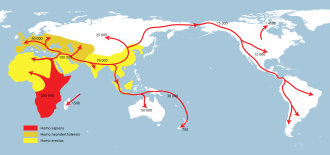

Recent African origin of modern humans

[21] Practically all of these early waves seem to have gone extinct or retreated back, and present-day humans outside Africa descend mainly from a single expansion about 70,000–50,000 years ago,[22][23][24][7][8][25][26][excessive citations] via the so-called "Southern Route".

[40] Beginning 135,000 years ago, tropical Africa experienced megadroughts which drove humans from the land and towards the sea shores, and forced them to cross over to other continents.

[50][51] These humans seem to have either become extinct or retreated back to Africa 70,000 to 80,000 years ago, possibly replaced by southbound Neanderthals escaping the colder regions of ice-age Europe.

[23] The discovery of stone tools in the United Arab Emirates in 2011 at the Faya-1 site in Mleiha, Sharjah, indicated the presence of modern humans at least 125,000 years ago,[14] leading to a resurgence of the "long-neglected" North African route.

[15][52][16][17] This new understanding of the role of the Arabian dispersal began to change following results from archaeological and genetic studies stressing the importance of southern Arabia as a corridor for human expansions out of Africa.

[53] In Oman, a site was discovered by Bien Joven in 2011 containing more than 100 surface scatters of stone tools belonging to the late Nubian Complex, known previously only from archaeological excavations in the Sudan.

This provides evidence for a distinct Stone Age technocomplex in southern Arabia, around the earlier part of the Marine Isotope Stage 5.

[55] They found that "the ancestors of Neanderthals from the Altai Mountains and early modern humans met and interbred, possibly in the Near East, many thousands of years earlier than previously thought".

[57][58] The group that crossed the Red Sea travelled along the coastal route around Arabia and the Persian Plateau to India, which appears to have been the first major settling point.

[40][60] Shell middens 125,000 years old have been found in Eritrea,[61] indicating that the diet of early humans included seafood obtained by beachcombing.

[48] It may have happened either pre- or post-Toba, a catastrophic volcanic eruption that took place between 69,000 and 77,000 years ago at the site of present-day Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia.

[48] Some research showing slower than expected genetic mutations in human DNA was published in 2012, indicating a revised dating for the migration to between 90,000 and 130,000 years ago.

[62] Some more recent research suggests a migration out-of-Africa of around 50,000-65,000 years ago of the ancestors of modern non-African populations, similar to most previous estimates.

The authors concluded that Basal-East Asian ancestry was far more widespread and the peopling of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania was more complex than previously anticipated.

[90] Genetic studies concluded that Native Americans descended from a single founding population that initially split from a Basal-East Asian source population in Mainland Southeast Asia around 36,000 years ago, at the same time at which the proper Jōmon people split from Basal-East Asians, either together with Ancestral Native Americans or during a separate expansion wave.

[93] According to Macaulay et al. (2005), an early offshoot from the southern dispersal with haplogroup N followed the Nile from East Africa, heading northwards and crossing into Asia through the Sinai.

[32] This hypothesis is supported by the relatively late date of the arrival of modern humans in Europe as well as by archaeological and DNA evidence.

[32] Based on an analysis of 55 human mitochondrial genomes (mtDNAs) of hunter-gatherers, Posth et al. (2016) argue for a "rapid single dispersal of all non-Africans less than 55,000 years ago".

[citation needed] A possible explanation is that these mutations occurred in East Africa shortly before the exodus and became the dominant haplogroups thereafter by means of the founder effect.

Results from mtDNA collected from aboriginal Malaysians called Orang Asli indicate that the haplogroups M and N share characteristics with original African groups from approximately 85,000 years ago, and share characteristics with sub-haplogroups found in coastal south-east Asian regions, such as Australasia, the Indian subcontinent and throughout continental Asia, which had dispersed and separated from their African progenitor approximately 65,000 years ago.

Since M is found in high frequencies in highlanders from New Guinea and the Andamanese and New Guineans have dark skin and Afro-textured hair, some scientists think they are all part of the same wave of migrants who departed across the Red Sea ~60,000 years ago in the Great Coastal Migration.

[105] This method does not appear to be reliable for the migration out of Africa; in contrast to human genetics, JCV strains associated with African populations are not basal.

[36] Admixture from archaic hominins of still earlier divergence times, estimated at 1.2 to 1.3 million years ago, was found in Pygmies, Hadza and five Sandawe in 2012.

[110] In addition to genetic analysis, Petraglia et al. also examines the small stone tools (microlithic materials) from the Indian subcontinent and explains the expansion of population based on the reconstruction of paleoenvironment.

He proposed that the stone tools could be dated to 35 ka in South Asia, and the new technology might be influenced by environmental change and population pressure.

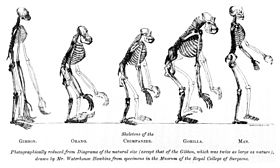

Isolated proponents of polygenism held forth in the mid-20th century, such as Carleton Coon, who thought as late as 1962 that H. sapiens arose five times from H. erectus in five places.

[122][123] In the 1980s, Allan Wilson together with Rebecca L. Cann and Mark Stoneking worked on genetic dating of the matrilineal most recent common ancestor of modern human populations (dubbed "Mitochondrial Eve").

To identify informative genetic markers for tracking human evolutionary history, Wilson concentrated on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is maternally inherited.

A reanalysis of LM3 and other ancient specimens from the area published in 2016, showed it to be akin to modern Aboriginal Australian sequences, inconsistent with the results of the earlier study.

[16] A Stanford University School of Medicine study was done by comparing Y-chromosome sequences and mtDNA in 69 men from different geographic regions and constructing a family tree.

Homo erectus greatest extent (yellow)

Homo neanderthalensis greatest extent (ochre)

Homo sapiens (red)

a: Exit of the L3 precursor to Eurasia. b: Return to Africa and expansion to Asia of basal L3 lineages with subsequent differentiation in both continents.