Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common encapsulated, Gram-negative, aerobic–facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium that can cause disease in plants and animals, including humans.

[3] The organism is considered opportunistic insofar as serious infection often occurs during existing diseases or conditions – most notably cystic fibrosis and traumatic burns.

[4] Because it thrives on moist surfaces, this bacterium is also found on and in medical equipment, including catheters, causing cross-infections in hospitals and clinics.

[citation needed] The genome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa consists of a relatively large circular chromosome (5.5–6.8 Mb) that carries between 5,500 and 6,000 open reading frames, and sometimes plasmids of various sizes depending on the strain.

[37] It is the most common cause of infections of burn injuries and of the outer ear (otitis externa), and is the most frequent colonizer of medical devices (e.g., catheters).

Cystic fibrosis patients are also predisposed to P. aeruginosa infection of the lungs due to a functional loss in chloride ion movement across cell membranes as a result of a mutation.

Since these bacteria thrive in moist environments, such as hot tubs and swimming pools, they can cause skin rash or swimmer's ear.

[13] These aeruginosa-specific core proteins, such as CntL, CntM, PlcB, Acp1, MucE, SrfA, Tse1, Tsi2, Tse3, and EsrC are known to play an important role in this species' pathogenicity.

Increasingly, it is becoming recognized that the iron-acquiring siderophore, pyoverdine, also functions as a toxin by removing iron from mitochondria, inflicting damage on this organelle.

[50] In higher plants, P. aeruginosa induces soft rot, for example in Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale cress)[51] and Lactuca sativa (lettuce).

[52][53] It is also pathogenic to invertebrate animals, including the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans,[54][55] the fruit fly Drosophila,[56] and the moth Galleria mellonella.

[60] P. aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen with the ability to coordinate gene expression in order to compete against other species for nutrients or colonization.

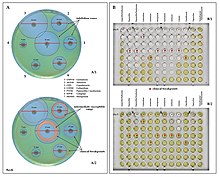

Regulation of gene expression can occur through cell-cell communication or quorum sensing (QS) via the production of small molecules called autoinducers that are released into the external environment.

P. aeruginosa employs five interconnected QS systems – las, rhl, pqs, iqs, and pch – that each produce unique signaling molecules.

Recently, it has been demonstrated that the rhl system partially controls las-specific factors, such as proteolytic enzymes responsible for elastolytic and staphylolytic activities, but in a delayed manner.

The intracellular concentration of cyclic di-GMP increases within seconds when P. aeruginosa touches a surface (e.g.: a rock, plastic, host tissues...).

[74] Biofilms of P. aeruginosa can cause chronic opportunistic infections, which are a serious problem for medical care in industrialized societies, especially for immunocompromised patients and the elderly.

Biofilms serve to protect these bacteria from adverse environmental factors, including host immune system components in addition to antibiotics.

Researchers consider it important to learn more about the molecular mechanisms that cause the switch from planktonic growth to a biofilm phenotype and about the role of QS in treatment-resistant bacteria such as P. aeruginosa.

[citation needed] When P. aeruginosa is isolated from a normally sterile site (blood, bone, deep collections), it is generally considered dangerous, and almost always requires treatment.

The isolation of P. aeruginosa from nonsterile specimens should, therefore, be interpreted cautiously, and the advice of a microbiologist or infectious diseases physician/pharmacist should be sought prior to starting treatment.

[83] Furthermore, mutations in the gene lasR drastically alter colony morphology and typically lead to failure to hydrolyze gelatin or hemolyze.

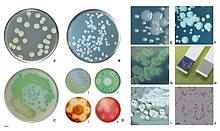

[citation needed] In certain conditions, P. aeruginosa can secrete a variety of pigments, including pyocyanin (blue), pyoverdine (yellow and fluorescent), pyorubin (red), and pyomelanin (brown).

Some recent studies have shown phenotypic resistance associated to biofilm formation or to the emergence of small-colony variants may be important in the response of P. aeruginosa populations to antibiotic treatment.

P. aeruginosa has also been reported to possess multidrug efflux pumps systems that confer resistance against a number of antibiotic classes, and the MexAB-OprM (Resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family) is considered as the most important[105].

Such findings have been reported in the case of rifampicin-resistant and colistin-resistant strains, in which decrease in infective ability, quorum sensing, and motility have been documented.

When P. aeruginosa is grown under in vitro conditions designed to mimic a cystic fibrosis patient's lungs, these genes mutate repeatedly.

[107] Two small RNAs, Sr0161 and ErsA, were shown to interact with mRNA encoding the major porin OprD responsible for the uptake of carbapenem antibiotics into the periplasm.

[118] Research on this bacterium's systems biology led to the development of genome-scale metabolic models that enable computer simulation and prediction of bacterial growth rates under varying conditions, including its virulence properties.

A pest risk analysis by the EAC was based on this bacterium's CABI's Crop Protection Compendium listing, following Kaaya & Darji 1989's initial detection in Kenya.