Socialist Republic of Croatia

The newly elected government of Franjo Tuđman moved the republic towards independence, formally seceding from Yugoslavia in 1991 and thereby contributing to its dissolution.

[8] On November 29, 1945, the Yugoslav Constituent Assembly held a session where it was decided that Croatia would be joined by five other republics in Yugoslavia: Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia and Macedonia.

[11] Republics had only formal autonomy; initially, communist Yugoslavia was a highly centralized state, based on the Soviet model.

[16] On 22 December 1990, the Parliament rejected the communist one-party system and adopted a liberal democracy through the Constitution of Croatia.

[20] Soon after they gained power, the Communists started to persecute former officials of the Independent State of Croatia in order to compromise them to the general public.

On 6 June 1946, the Supreme Court of the SR Croatia sentenced some of the leading officials of the NDH, including Slavko Kvaternik, Vladimir Košak, Miroslav Navratil, Ivan Perčević, Mehmed Alajbegović, Osman Kulenović and others.

The federal government realised that it was unable to service the interest on its loans and started negotiations with the IMF that continued for years.

[22] The debt crisis, together with soaring inflation, forced the federal government to introduce measures such as the foreign currency law for earnings of export firms.

Ante Marković, a Bosnian Croat who at the time was the Croatian head of government, said that Croatia would lose around $800 million because of that law.

The growing crisis in Kosovo, the nationalist memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, the emergence of Slobodan Milošević as the leader of Serbia, and everything else that followed provoked a very negative reaction in Croatia.

The fifty-year-old rift was starting to resurface, and the Croats increasingly began to show their own national feelings and express opposition towards the Belgrade regime.

On October 17, 1989, the rock group Prljavo kazalište held a major concert before almost 250,000 people in the central Zagreb city square.

This caused first the Slovenian and then Croatian delegations (led by Milan Kučan and Ivica Račan, respectively) to leave the Congress in protest and marked a culmination in the rift of the ruling party.

Serb politicians feared the loss of influence they previously had through their membership of the League of Communists in Croatia (that some Croats claimed was disproportionate).

The availability of mass media allowed for propaganda to be spread fast and spark jingoism and fear, creating a war climate.

The dying country had yet to see a few more Serb leadership's attempts to push the plan for centralizing the power in Belgrade, but because of resistance in all other republics, the crisis only deteriorated.

In the early years of the SFR Yugoslavia, Communist members suppressed critics towards the Soviet Union and harbored sympathies towards it.

Because of the 4-year partisan war, bombings, over-exploitation of raw materials and agricultural resources, and destruction of roads and industrial facilities, the state entered into economic chaos.

The recruitment for volunteer work was conducted with propaganda promising a better communist future, especially for members of Yugoslav partisans and youth.

This decision was a double-edged sword: while the poor segment of society was satisfied by it, the large majority of the population was resistant and ready to revolt.

[28] Just like in the Soviet Union, the state controlled the entire economy, while free trade was forbidden in favour of central planning.

[34] For this process, the state needed a large number of officials who were members of the Communist Party, receiving orders from the Politburo, thus leaving the Yugoslav republic without any power in the economy.

[35] Moreover, the liquidation of the private sector, cleansing of the state apparatus and high officials and their replacement by half-educated partisans, drastic reduction of the gap between payments of ministers and workers (3:1), and emigration and deaths of the bourgeois class led to the disappearance of the middle class in the social structure, which had a negative effect on social life.

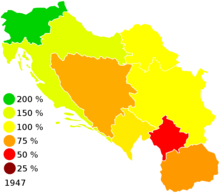

On 17 January 1947, Kardelj stated to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia that Yugoslavia would be industrially stronger than Austria and Czechoslovakia.

[38] All across the country, the state built the sites, and all projects of industrialization and electrification were made with propaganda that the population would have lower poverty and unemployment.

[37] The majority of residents were Roman Catholics and approximately 12% of the population were Orthodox Christians of the Serbian Patriarchy, with a small number of other religions.

Due to strained relationships between the Holy See and communist Yugoslav officials, no new Catholic bishops were appointed in the People's Republic of Croatia until 1960.

This left the dioceses of Križevci, Đakovo-Osijek, Zadar, Šibenik, Split-Makarska, Dubrovnik, Rijeka and Poreč-Pula without bishops for several years.

[39] From the mid-1950s, there were only four seated bishops in Croatia in three dioceses: Aloysius Stepinac, Franjo Salis-Seewiss, Mihovil Pušić, and Josip Srebrnič.

He was sentenced to sixteen years' imprisonment, but in December 1951, he was released to house arrest at his home in Krašić near Jastrebarsko, where he died in 1960.