Croatian literature

In later periods, elements of that language came to be used in expressive ways and as a signal of "high style", incorporating current vernacular words and becoming capable of transferring knowledge on a wide range of subjects, from law and theology, chronicles and scientific texts, to works of literature.

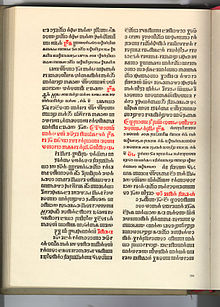

[4] The Povlja tablet (Croatian: Povaljska listina) is the earliest document written in the Cyrillic script, dating from the 12th century and tracing its origin to Brač,[5] it features the standard "archaic" Chakavian dialect.

In Split, the Dalmatian humanist Marko Marulić was widely known in Europe at the time for his writings in Latin, but his major legacy is considered to be his works in Croatian,[7] the most celebrated of which is the epic poem Judita, written in 1501 and published in Venice in 1521.

[8] The next important artistic figure in the early stages of the Croatian Renaissance was Petar Hektorović, the song collector and poet from the island of Hvar, most notable for his poem Fishing and Fishermen's Talk.

The first Croatian novel,[10][11] Planine (Mountains) written by Petar Zoranić and published posthumously in 1569 in Venice, featured the author as an adventurer, portraying his passionate love towards a native girl.

The artistic range is not as great in this period as during the Renaissance or the Baroque, but there is a greater distribution of works and a growing integration of the literature of the separate areas of Dalmatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Slavonia, Dubrovnik and northwestern Croatia, which will lead into the national and political movements of the 19th century.

He also published a number of other seminal works, including Zbirka crkvenih pjesama ("Collection of Church Songs"; 1757), an anthology of traditional songs and hymns from the Samobor region and Fundamentum cantus Gregoriani, seu chroralis pro Captu Tyronis discipuli, ex probatis authoribus collectum, et brevi, ac facili dialogica methodo in lucem expositum opera, ac studio ("The basis of the singing of Gregorian melodies, or the chorales definite for the disciples saw it, from the classical authors, and deposited in a short time, exposed to the light of the work of the Method in the rich and of easy dialogic, and a studio.")

Some literary historians refer to it as "Photorealism", a time marked by the author August Šenoa[18] whose work combined the flamboyant language of national romanticism with realistic depictions of peasant life.

Ksaver Šandor Gjalski[27] dealt with subjects from Zagorje's upper class (Pod starimi krovovi, Under Old Roofs, 1886), affected poetic realism and highlighted the political situation in »U noći« (In the Night, 1887).

Josip Draženović's Crtice iz primorskoga malogradskoga života (Sketches from a Coastal Small Town Life, 1893) focused on people and their relationships on the Croatian coast at the end of the 19th century.

Twelve authors contributed to the anthology: Ivo Andrić, Vladimir Čerina, Vilko Gabarić, Karl Hausler, Zvonko Milković, Stjepan Parmačević, Janko Polić Kamov, Tin Ujević, Milan Vrbanić, Ljubo Wiesner and Fran Galović.

Janko Polić Kamov,[33] in his short life, was an early forerunner, with his modernist novel Isušena kaljuža (The Drained Swamp, 1906–1909) now considered to be the first major Croatian prose work of the genre.

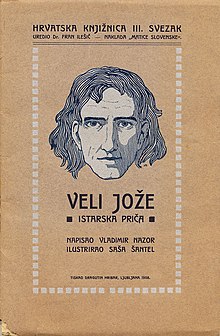

In this, they were strongly influenced by the expressive and ideological works of sculptor Ivan Meštrović and writers Ivo Vojnović and Vladimir Nazor, who, before the First World War, had revived common Slavic mythology.

Ljubo Micić was the most radical promoter of the avant-garde in literature, music, and art, advocating Zenitism as a synthesis of the original Balkan spirit and contemporary European trends (futurism, expressionism, dadaism, surrealism).

Miroslav Krleža In 1923, he launched his second magazine, Književna republika (Literary Republic, banned in 1927), bringing together leading leftist writers, focusing on inequality and social injustice, offering a sharp critique of the ruling regime in Yugoslavia.

However, the Matica administration gradually eased out the leftist writers, particularly after Filip Lukas' article Ruski komunizam spram nacionalnog principal (Russian Communism as opposed to National Principles, 1933).

His work culminated in some of the best Croatian prose, the modernist concept of the Proljeća Ivana Galeba (The Spring of John Seagull, 1957), a series of essays in which he addressed the issue of artistic creation.

Jure Franičević Pločar[55] wrote poetry in the čakav and Štokav dialects, but established himself primarily as a novelist, with a series of books about the NOB period, written without sentiment, based on the complex psychological states of the characters.

Among the writers of this generation, the most significant prose was written by Slobodan Novak, in his collections Izgubljeni zavičaj (Lost Homeland, 1955), Tvrdi grad (Hard City, 1961), Izvanbrodski dnevnik (Outboard Diary, 1977) and the novel Mirisi, zlato i tamjan (Scents, Gold and Incense, 1968) in which he dealt with the dilemmas of the modern intellectual, with a sense of existential absurdity.

Antun Šoljan was a versatile author: a poet, novelist Izdajice (Traitor, 1961), Kratki izlet (Short trip, 1965), Luka (Port, 1974), playwright, critic, feuilletonist, anthologist, editor of several journals and translator.

He also wrote some notable works for adults, prose and drama, based on his linguistic and stylistic virtuosity and wit that occasionally become happy pastiches of literary stereotypes from domestic and world literature.

In the early 1960s, the magazine Razlog (Reason, 1961–68) and the associated library featured writers born mainly around 1940, characterized by a pronounced awareness of generational and aesthetic distinctiveness from other groups within Croatian literature.

He was significant as a critic and anthologist, seeking to reinterpret ideas about post-war Croatian poetry, affirming some previously neglected early modernists (Radovan Ivšić, Josip Stošić[65] ) and writers who built autonomous poetic worlds, especially Nikola Šop.

Among the many poets who published their first books at the end of the 1960s, and early 1970s, were Ernest Fišer, Željko Knežević, Mario Suško, Gojko Sušac, Jordan Jelić, Dubravka Oraić Tolić, Ivan Rogić Nehajev, Andriana Škunca, Vladimir Reinhofer, Nikola Martić, Ivan Kordić, Jakša Fiamengo, Momčilo Popadić, Enes Kišević, Tomislav Marijan Bilosnić, Džemaludin Alić, Stjepan Šešelj, Sonja Manojlović, Mile Pešorda, Tomislav Matijević, Božica Jelušić, Željko Ivanković, Dražen Katunarić, and Mile Stojić.

The new generation of authors in the early 1970s had a fondness for fantasy and was inspired by contemporary Latin American fiction, Russian symbolism and avant-garde (especially Bulgakov), then Kafka, Schulz, Calvino, and Singer.

Towards the end of the 1970s, many writers were integrating so-called trivial genres (detective stories, melodrama) into high literature, while others were writing socially critical prose, for example, romance thrust into novels, which was popular in the 1970s.

Stjepan Čuić[74] in his early work Staljinova slika i druge priče (Stalin's Picture and Other Stories, 1971), intertwined fantasy and allegorical narrative dealing with the individual's relationship with a totalitarian political system.

In the mid-1980s, in the journal Quorum, a series of new prose writers, poets and critics appeared: Damir Miloš, Ljiljana Domić, Branko Čegec, Krešimir Bagić, Vlaho Bogišić, Hrvoje Pejaković, Edo Budiša, Julijana Matanović, Goran Rem, Delimir Rešicki, Miroslav Mićanović, Miloš Đurđević, Nikola Petković and several young dramatic writers, such as Borislav Vujčić, Miro Gavran, Lada Kaštelan, Ivan Vidić, and Asja Srnec-Todorović.

In 1957, the journal Umjetnost riječi (Art of Words) was launched, collecting together a group of theoeticians and literary historians who would form the core of the Zagrebačke stilističke škole (Zagreb stylistic school).

During the second half of the 20th century, scholars in the field of Croatian literary studies included: Maja Bošković-Stulli, Viktor Žmegač, Darko Suvin, Milivoj Solar, Radoslav Katičić, Pavao Pavličić, Andrea Zlatar.