Pain in crustaceans

[7][8][9] In 1789, the British philosopher and social reformist, Jeremy Bentham, addressed in his book An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation the issue of our treatment of animals with the following often quoted words: "The question is not, Can they reason?

[12] In his interactions with scientists and other veterinarians, Rollin was regularly asked to "prove" that animals are conscious, and to provide "scientifically acceptable" grounds for claiming that they feel pain.

Convergent evidence indicates that non-human animals have the neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and neurophysiological substrates of conscious states along with the capacity to exhibit intentional behaviors.

"[25] Veterinary articles have been published stating both reptiles[26][27][28] and amphibians[29][30][31] experience pain in a way analogous to humans, and that analgesics are effective in these two classes of vertebrates.

[35] This is the ability to detect noxious stimuli which evoke a reflex response that rapidly moves the entire animal, or the affected part of its body, away from the source of the stimulus.

[citation needed] In vertebrates, nociceptive responses involve the transmission of a signal along a chain of nerve fibres from the site of a noxious stimulus at the periphery, to the spinal cord.

This process evokes a reflex arc response such as flinching or immediate withdrawal of a limb, generated at the spinal cord and not involving the brain.

Many crustacean species, including the rockpool prawn (Palaemon elegans),[37] exhibit the caridoid escape reaction – an immediate, nociceptive, reflex tail-flick response to noxious stimuli (see here[38]).

For example, crustaceans living in an aquatic world can maintain a certain level of buoyancy, so the risk of collision due to gravity is limited compared with a terrestrial vertebrate.

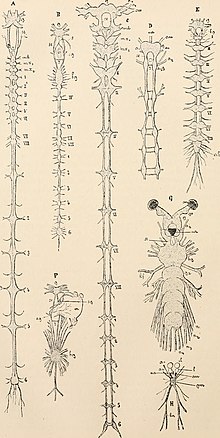

[42] Neurons functionally specialized for nociception have been documented in other invertebrates including the leech Hirudo medicinalis, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the molluscs Aplysia californica and Cepaea nemoralis.

Changes in neuronal activity induced by noxious stimuli have been recorded in the nervous centres of Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster and larval Manduca sexta.

Each ganglion receives sensory and movement information via nerves coming from the muscles, body wall, and appendages such as walking legs, swimmerets and mouthparts.

[citation needed] When shore crabs (Hemigrapsus sanguineus) have formalin injected into the cheliped (claw), this evokes specific nociceptive behavior and neurochemical responses in the thoracic ganglia and the brain.

"[48] Lynne Sneddon (University of Liverpool) proposes that to suggest a function suddenly arises without a primitive form defies the laws of evolution.

[52] RT-PCR research on the American lobster (Homarus americanus) has revealed the presence of a Mu-opioid receptor transcript in neural and immune tissues, which exhibits a 100% sequence identity with its human counterpart.

In lobsters which have had a pereiopod (walking leg) cut off or been injected with the irritant lipopolysaccharide, the endogenous morphine levels initially increased by 24% for haemolymph and 48% for the nerve cord.

[62] Injection of formalin into the cheliped of shore crabs (Hemigrapsus sanguineus) evokes specific nociceptive behavior and neurochemical responses in the brain and thoracic ganglion.

[66] Immediately after the injection of formalin (an irritant in mammals) or saline into one cheliped (the leg which ends with the claw), shore crabs move quickly into the corner of the aquarium and "freeze" after 2 to 3 seconds.

After 1 to 3 minutes, these injected animals are fidgety and exhibit a wide range of movements such as flexion, extension, shaking or rubbing the affected claw.

Intense rubbing of the claw results in autotomy (shedding) in 20% of animals of the formalin-treated group whereas saline-injected crabs do not autotomise the injected cheliped.

The scientists conducting this study commented "the present results obtained in crabs may be indicative of pain experience rather than relating to a simple nociceptive reflex".

In one study, no behavioural or neural changes in three different crustacean species (red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii), white shrimp (Litopenaeus setiferus) and Palaemonetes sp.)

They quickly learn to respond to these associations by walking to a safe area in which the shock is not delivered (crayfish) or by refraining from entering the light compartment (crab).

[40] In 2009, Elwood and Mirjam Appel showed that hermit crabs make motivational trade-offs between electric shocks and the quality of the shells they inhabit.

Moreover, because the researchers did not offer the new shells until after the electrical stimulation had ended, the change in motivational behavior was the result of memory of the noxious event, not an immediate reflex.

Furthermore, shocked crayfish had relatively higher brain serotonin concentrations coupled with elevated blood glucose, which suggests a stress response.

[81] In 2005 a review of the literature by the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety tentatively concluded that "it is unlikely that [lobsters] can feel pain," though they note that "there is apparently a paucity of exact knowledge on sentience in crustaceans, and more research is needed."

The report assumes that the violent reaction of lobsters to boiling water is a reflex response (i.e. does not involve conscious perception) to noxious stimuli.

[3] A European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) 2005 publication[82] stated that the largest of decapod crustaceans have complex behaviour, a pain system, considerable learning abilities and appear to have some degree of awareness.

[84] The EFSA summarized that the killing methods most likely to cause pain and distress are:[85] A device called the CrustaStun has been invented to electrocute shellfish, such as lobsters, crabs, and crayfish, before cooking.