Pair production

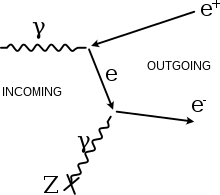

Pair production is the creation of a subatomic particle and its antiparticle from a neutral boson.

Examples include creating an electron and a positron, a muon and an antimuon, or a proton and an antiproton.

(As the electron is the lightest, hence, lowest mass/energy, elementary particle, it requires the least energetic photons of all possible pair-production processes.)

[1] All other conserved quantum numbers (angular momentum, electric charge, lepton number) of the produced particles must sum to zero – thus the created particles shall have opposite values of each other.

The probability of pair production in photon–matter interactions increases with photon energy and also increases approximately as the square of atomic number of (hence, number of protons in) the nearby atom.

These interactions were first observed in Patrick Blackett's counter-controlled cloud chamber, leading to the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physics.

The photon must have higher energy than the sum of the rest mass energies of an electron and positron (2 × 511 keV = 1.022 MeV, resulting in a photon wavelength of 1.2132 pm) for the production to occur.

The photon must be near a nucleus in order to satisfy conservation of momentum, as an electron–positron pair produced in free space cannot satisfy conservation of both energy and momentum.

[5] Because of this, when pair production occurs, the atomic nucleus receives some recoil.

We can square the conservation equation However, in most cases the recoil of the nucleus is small compared to the energy of the photon and can be neglected.

and expanding the remaining relation Therefore, this approximation can only be satisfied if the electron and positron are emitted in very nearly the same direction, that is,

An exact derivation of the kinematics can be done taking into account the full quantum mechanical scattering of photon and nucleus.

The energy transfer to electron and positron in pair production interactions is given by where

In general the electron and positron can be emitted with different kinetic energies, but the average transferred to each (ignoring the recoil of the nucleus) is The exact analytic form for the cross section of pair production must be calculated through quantum electrodynamics in the form of Feynman diagrams and results in a complicated function.

is some complex-valued function that depends on the energy and atomic number.

In 2008 the Titan laser, aimed at a 1 millimeter-thick gold target, was used to generate positron–electron pairs in large numbers.

[7] Pair production is invoked in the heuristic explanation of hypothetical Hawking radiation.

In a region of strong gravitational tidal forces, the two particles in a pair may sometimes be wrenched apart before they have a chance to mutually annihilate.

Pair production is also the mechanism behind the hypothesized pair-instability supernova type of stellar explosion, where pair production suddenly lowers the pressure inside a supergiant star, leading to a partial implosion, and then explosive thermonuclear burning.