Quantum electrodynamics

[1][2][3] In essence, it describes how light and matter interact and is the first theory where full agreement between quantum mechanics and special relativity is achieved.

[2][3] In technical terms, QED can be described as a very accurate way to calculate the probability of the position and movement of particles, even those massless such as photons, and the quantity depending on position (field) of those particles, and described light and matter beyond the wave-particle duality proposed by Albert Einstein in 1905.

Richard Feynman called it "the jewel of physics" for its extremely accurate predictions of quantities like the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron and the Lamb shift of the energy levels of hydrogen.

[4][5] The first formulation of a quantum theory describing radiation and matter interaction is attributed to British scientist Paul Dirac, who during the 1920s computed the coefficient of spontaneous emission of an atom.

[7] Dirac described the quantization of the electromagnetic field as an ensemble of harmonic oscillators with the introduction of the concept of creation and annihilation operators of particles.

In the following years, with contributions from Wolfgang Pauli, Eugene Wigner, Pascual Jordan, Werner Heisenberg and Enrico Fermi,[8] physicists came to believe that, in principle, it was possible to perform any computation for any physical process involving photons and charged particles.

However, further studies by Felix Bloch with Arnold Nordsieck,[9] and Victor Weisskopf,[10] in 1937 and 1939, revealed that such computations were reliable only at a first order of perturbation theory, a problem already pointed out by Robert Oppenheimer.

[11] At higher orders in the series infinities emerged, making such computations meaningless and casting doubt on the theory's internal consistency.

Based on Bethe's intuition and fundamental papers on the subject by Shin'ichirō Tomonaga,[16] Julian Schwinger,[17][18] Richard Feynman[1][19][20] and Freeman Dyson,[21][22] it was finally possible to produce fully covariant formulations that were finite at any order in a perturbation series of quantum electrodynamics.

[23] Their contributions, and Dyson's, were about covariant and gauge-invariant formulations of quantum electrodynamics that allow computations of observables at any order of perturbation theory.

[2]: 128 Neither Feynman nor Dirac were happy with that way to approach the observations made in theoretical physics, above all in quantum mechanics.

Building on Schwinger's pioneering work, Gerald Guralnik, Dick Hagen, and Tom Kibble,[25][26] Peter Higgs, Jeffrey Goldstone, and others, Sheldon Glashow, Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam independently showed how the weak nuclear force and quantum electrodynamics could be merged into a single electroweak force.

Near the end of his life, Richard Feynman gave a series of lectures on QED intended for the lay public.

The basic rules of probability amplitudes that will be used are:[2]: 93 The indistinguishability criterion in (a) is very important: it means that there is no observable feature present in the given system that in any way "reveals" which alternative is taken.

In such a case, one cannot observe which alternative actually takes place without changing the experimental setup in some way (e.g. by introducing a new apparatus into the system).

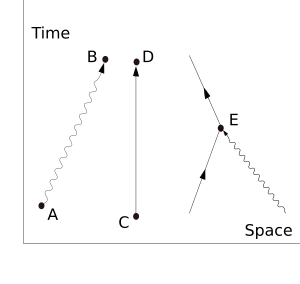

One is that whereas we might expect in our everyday life that there would be some constraints on the points to which a particle can move, that is not true in full quantum electrodynamics.

There is a nonzero probability amplitude of an electron at A, or a photon at B, moving as a basic action to any other place and time in the universe.

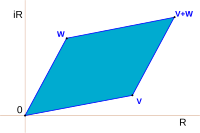

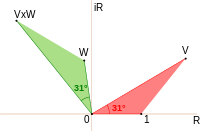

Feynman avoids exposing the reader to the mathematics of complex numbers by using a simple but accurate representation of them as arrows on a piece of paper or screen.

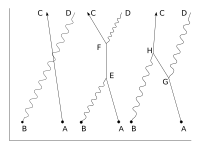

The simplest case would be two electrons starting at A and B ending at C and D. The amplitude would be calculated as the "difference", E(A to D) × E(B to C) − E(A to C) × E(B to D), where we would expect, from our everyday idea of probabilities, that it would be a sum.

A problem arose historically which held up progress for twenty years: although we start with the assumption of three basic "simple" actions, the rules of the game say that if we want to calculate the probability amplitude for an electron to get from A to B, we must take into account all the possible ways: all possible Feynman diagrams with those endpoints.

If adding that detail only altered things slightly, then it would not have been too bad, but disaster struck when it was found that the simple correction mentioned above led to infinite probability amplitudes.

However, Feynman himself remained unhappy about it, calling it a "dippy process",[2]: 128 and Dirac also criticized this procedure as "in mathematics one does not get rid of infinities when it does not please you".

[24] Within the above framework physicists were then able to calculate to a high degree of accuracy some of the properties of electrons, such as the anomalous magnetic dipole moment.

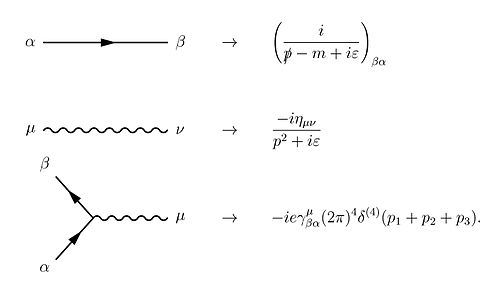

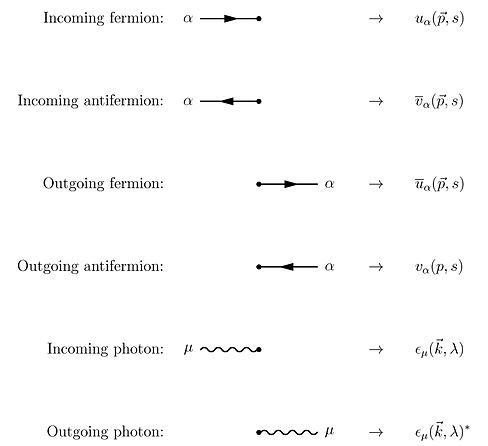

"[2]: 152 Mathematically, QED is an abelian gauge theory with the symmetry group U(1), defined on Minkowski space (flat spacetime).

This permits us to build a set of asymptotic states that can be used to start computation of the probability amplitudes for different processes.

, since these internal ("virtual") particles are not constrained to any specific energy–momentum, even that usually required by special relativity (see Propagator for details).

The predictive success of quantum electrodynamics largely rests on the use of perturbation theory, expressed in Feynman diagrams.

This process, called the Schwinger effect,[28] cannot be understood in terms of any finite number of Feynman diagrams and hence is described as nonperturbative.

To overcome this difficulty, a technique called renormalization has been devised, producing finite results in very close agreement with experiments.

The reason for this is that to get observables renormalized, one needs a finite number of constants to maintain the predictive value of the theory untouched.