Palace of the Soviets

The Palace of the Soviets (Russian: Дворец Советов, romanized: Dvorets Sovetov) was a project to construct a political convention center in Moscow on the site of the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.

The staggered stack of ribbed cylinders crowned with a 100-metre (330 ft) statue of Vladimir Lenin blended Art Deco and Neoclassical influences with contemporary American skyscraper technology.

Dmitrij Chmelnizki [de] claims Stalin was the project's sole initiator;[21] Sergey Kuznetsov counters that the idea was pitched by Alexei Rykov.

The Construction Council was a decorative[26] political committee chaired by Kliment Voroshilov and later Vyacheslav Molotov;[27][22][28] it served as a proxy for announcing decisions made by Stalin and the Politburo.

[29][30][31][32] A recent repatriant from Italy and a long-time student of Italian architect Armando Brasini, Iofan was a maverick within the Soviet architectural community and had no obligations to any group.

[35] By 1931 he had a proven record of completing high-profile projects, including the enormous[d] House on the Embankment with its cinema hall [ru]—the largest modern auditorium in Moscow.

[37] Kryukov, Mikhailov, Rykov, Yenukidze and Iofan's colleagues at the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee would be killed in Stalin's purges, but the unsinkable architect would survive unharmed and retain his office, despite the incriminating connections.

[43] The plan was soon implemented in a series of architectural competitions, where Iofan acted as primus inter pares (first among equals) in public and the éminence grise (powerful decision maker) behind the scenes.

[41] In March 1931, the Construction Council chose a compact site in the former Okhotny Ryad Street market, just a few hundred meters (yards) north-west from the Kremlin and Red Square.

[46] It required extensive demolition and presented so far unknown technical challenges,[47][19] but it was the largest site and it formed a tight visual ensemble with Iofan's House on the Embankment.

[45] According to Sona Hoisington, the decision was final, but its main objective was not the palace but the destruction of the cathedral,[50] with the project being a purely political statement, made without prior feasibility studies and completely disregarding the economics.

The brief, prepared by Iofan and signed by Kryukov, reiterated the monumentality and emphasizing the uniqueness of the future palace: it should be radically different from any existing public building.

[54] Iofan had considered various alternatives, and ruled out compact centric floor plans in favor of a sprawling group of buildings aligned along the north–south axis of the cathedral site.

[56] The USDS did not name a clear winner but cautiously praised an entry by Heinrich Ludwig,[g] an enormous pentagonal enlargement of Lenin's Mausoleum devoid of any stylistic cues.

[60] The USS claimed no single group could overcome the project's unprecedented challenges; it requires a joint effort of "all living creative forces of the Soviet society".

[61] Another covert purpose of the competition—suppression of undesirable architecture in a manner similar to the "Degenerate art" campaign in Germany—would be revealed by Alexey Tolstoy (another party insider) later, just before the announcement of the winners.

[62][j] The Soviet press praised his innovative, logical and convenient floor plan as late as 1940, but the jury felt the high-rise exoskeleton supporting the saddle roof was inappropriate for downtown Moscow.

The draft disposed with former Constructivist novelty[72] The shape of the main hall changed from a parabolic dome to a stack of flat cylinders and, according to Katherine Zubovich, acquired "more italianate form".

[72] It was certainly not unique to Hamilton's entry: similar ribbed facades, a staple of American Art Deco, were also used by Alexey Dushkin, Iosif Langbard, Dmitry Chechulin and Iofan himself.

[84] The USDS required all architects to abandon a sprawling, squat design in favor of a single tall, compact, and monumental structure, avoiding any resemblance to church architecture.

[95][94] The winning design closely followed Iofan's earlier proposal — a compact, ziggurat-like stack of three cylinders perched on a massive stylobate and flanked with colonnades, ramps and grand staircases.

[5] According to Andrey Barkhin, the true purpose of the fourth stage was to narrow down stylistic choice to one of two alternatives: either following an existing, historical model, or creating something completely new.

[102] Rudolf Wolters, who came to Novosibirsk in the summer of 1932, reported that by the time of his arrival the provincial party executives had already received orders from Moscow to build "in classical style" only.

[102] The overwhelming majority of Soviet, Russian and foreign authors, with the notable exception of Antonia Cunliffe, agree the competitions represented a deliberate rejection of modernism in favor of monumental historicism.

[116][n] The theatrical, dramatic visionary architecture that emerged from this collaboration was approved and publicized to great pomp in February 1934 despite a complete lack of technical and economic estimates.

[121] The location of the statue and the design by Sergey Merkurov remained controversial throughout the 1930s and were harshly criticized in public by Boris Korolyov, Nikolai Tomsky, Martiros Saryan and other involved artists.

[143] The lower segment, 60 metres (200 ft) tall, comprised 32 pairs of vertical columns placed around the grand hall and connected to the foundation slab via massive riveted "shoes".

[150] The designers selected greyish blue Ukrainian labradorite for the basement and pale grey granite from the Daut River [ru] valley for the rest of the structure.

The concept developed by the Vesnin brothers and Ivan Leonidov in the 1920s was incorporated in the 1935 urban reconstruction plan [ru] in its basic form,[160] and was subsequently reexamined in numerous drafts and proposals.

[201] The winning, and probably the most artistically valuable proposal, by Alexander Vlasov [ru], was an outright modernist glass box—a huge winter garden with three oval halls floating in a sea of greenery.

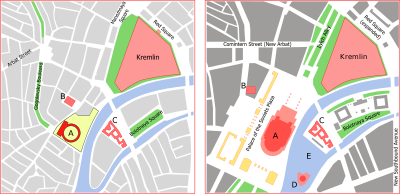

2 by 2 kilometres (1.2 mi × 1.2 mi). Legend: A: Palace of the Soviets (foundation of the core and the northern wing of the stylobate), B: Pushkin Museum (to be relocated), C: House on the Embankment, D: Aviators' Memorial, E: Reflective pool. Note the absence of Lenin's Mausoleum on the plan.