Paleoneurobiology

The cranium is unique in that it grows in response to the growth of brain tissue rather than genetic guidance, as is the case with bones that support movement.

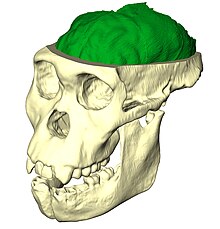

[2] Paleoneurobiologists analyze endocasts that reproduce details of the external morphology of brains that have been imprinted on the internal surfaces of skulls.

[4] The late part of the 19th century in comparative anatomy was heavily influenced by the work of Charles Darwin in the On the Origin of Species in 1859.

In 1873, with this tool in hand, Camillo Golgi began to cellularly detail the brain and employ techniques to perfect axonal microscoping.

Her father Ludwig Edinger, himself a pioneer in comparative neurology, provided Tilly with invaluable exposure to his field and the scientific community at large.

While preparing her doctoral dissertation, Edinger encountered a natural brain endocast of Nothosaurus, a marine reptile from the Mesozoic era.

The field was formally defined with the publication of Die fossilen Gehirne (Fossil Brains) in 1929 which compiled knowledge on the subject that had previously been scattered in a wide variety of journals and treated as isolated events.

[6] While still in Germany, Edinger began studying extant species from a paleoneurobiological perspective by making inferences about evolutionary brain development in seacows using stratigraphic and comparative anatomical evidence.

Edinger continued her research in Nazi Germany until the night of November 9, 1938, when thousands of Jews were killed or imprisoned in what became known as Kristallnacht.

Eventually her visa quota number was called and she was able to immigrate to the United States where she took on a position as a research fellow at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology.

The bibliography, Paleoneurology 1804–1966, was completed and published by colleagues posthumously in 1975 due to the untimely death of Edinger from injuries sustained during a traffic accident in 1967.

[6] Paleoneurobiologists Ralph L. Holloway and Dean Falk disagree about the interpretation of a depression on the Australopithecus afarensis AL 162-28 endocast.

The debate between Holloway and Falk is so intense that between 1983 and 1985, they published four papers on the identification of the medial end of the lunate sulcus of the Taung endocast (Australopithecus africanus), which only further strengthened the division between each scientist's respective opinion.

Endocasts can be formed naturally by sedimentation through the cranial foramina which becomes rock-hard due to calcium deposition over time, or artificially by creating a mold from silicon or latex that is then filled with plaster-of-Paris while sitting in a water bath to equalize forces and retain the original shape.

[10] Recent development of advanced computer graphics technology have allowed scientists to more accurately analyze of brain endocasts.

M. Vannier and G. Conroy of Washington University School of Medicine have developed a system that images and analyzes surface morphologies in 3D.

[11] Radiologist, paleoanthropologists, computer scientists in both the United States and Europe have collaborated to study such fossils using virtual techniques.

Much of this analysis is focused on interpreting sulcal patterns, which is difficult because traces are often hardly recognizable, and there are no clear landmarks to use as reference points.

[1] Therefore, a large portion of the field of paleoneurobiology arises out of developing more detailed procedures that increase the resolution and the reliability of interpretations.

For example, Holloway and Post calculate EQ by the following equation: Brain volume is prominent in the scientific literature for discussing taxonomic identification, behavioral complexity, intelligence, and dissimilar rates of evolution.

This degree of variation is almost equivalent to the total increase in volume from australopithecine fossils to modern humans, and brings into question the validity of relying on cranial capacity as a measurement of sophistication.

Geometric morphometrics (systems of coordinates superimposed over the measurements of the endocast) are often applied to allow comparison between specimens of varying size.

[7][13] Convolutions, the individual gyri and sulci that compose the folds of the brain, are the most difficult aspect of an endocast to accurately assess.

[7] Because meningeal blood vessels comprise part of the outermost layer of the brain, they often leave vascular grooves in the cranial cavity that are captured in endocasts.

Endocranial vasculature originates around the foramina in the skull and in a living body would supply blood to the calvaria and dura mater.

Endocasts also reveal traits of the ancient brain including relative lobe size, blood supply, and other general insight into the anatomy of evolving species.

The limited scale and completeness of the fossil record inhibits the ability of paleoneurobiology to accurately document the course of brain evolution.

Since there is no proven direct relationship between brain size and intelligence, only inferences can be made regarding the developing behavior of ancient relatives of the genus Homo.

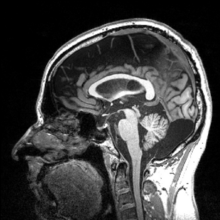

Recent studies by Emiliano Bruner, Manuel Martin-Loechesb, Miguel Burgaletac, and Roberto Colomc have investigated the connection between midsagittal brain shape and mental speed.

[19] The aim is to determine the genetic mechanisms that lead to focal or asymmetrical brain atrophy resulting in syndromic presentations that affect gait, hand movements (any sort of locomotion), language, cognition, mood and behavior disorders.