Pancreaticoduodenectomy

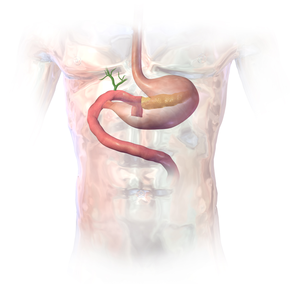

A pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as a Whipple procedure, is a major surgical operation most often performed to remove cancerous tumours from the head of the pancreas.

However, not all lymph nodes are removed in the most common type of pancreaticoduodenectomy because studies showed that patients did not benefit from the more extensive surgery.

[3] At the very beginning of the procedure, after the surgeons have gained access to the abdomen, the surfaces of the peritoneum and the liver are inspected for disease that has metastasized.

[4] The shared blood supply of the pancreas, duodenum and common bile duct necessitates en bloc resection of these multiple structures.

Surgery may follow neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which aims to shrink the tumor and increase the likelihood of complete resection.

Depending on the location and extension of the cholangiocarcinoma, curative surgical resection may require hepatectomy, or removal of part of the liver, with or without pancreaticoduodenectomy.

In rare cases when this pattern of trauma has been reported, it has been caused by a lap seat belt in motor vehicle accidents.

In order to determine if there are metastases, surgeons will inspect the abdomen at the beginning of the procedure after gaining access.

This may spare the patient the large abdominal incision that would occur if they were to undergo the initial part of a pancreaticoduodenectomy that was cancelled due to metastatic disease.

This may lead to another operation shortly thereafter in which the remainder of the pancreas (and sometimes the spleen) is removed to prevent further spread of infection and possible morbidity.

[20][21] In practice, it shows similar long-term survival as a Whipple's (pancreaticoduodenectomy + hemigastrectomy), but patients benefit from improved recovery of weight after a PPPD, so this should be performed when the tumour does not involve the stomach and the lymph nodes along the gastric curvatures are not enlarged.

Many studies have shown that hospitals where a given operation is performed more frequently have better overall results (especially in the case of more complex procedures, such as pancreaticoduodenectomy).

Even at high-volume hospitals, morbidity has been found to vary by a factor of almost four depending on the number of times the surgeon has previously performed the procedure.

[25] de Wilde et al. have reported statistically significant mortality reductions concurrent with centralization of the procedure in the Netherlands.

Delayed gastric emptying, normally defined as an inability to tolerate a regular diet by the end of the first post-op week and the requirement for nasogastric tube placement, occurs in approximately 17% of operations.

Pancreatic leak or pancreatic fistula, defined as fluid drained after postoperative day 3 that has an amylase content greater than or equal to 3 times the upper limit of normal, occurs in 5–10% of operations,[31][32] although changes in the definition of fistula may now include a much larger proportion of patients (upwards of 40%).

Ileus, which refers to functional obstruction or aperistalsis of the intestine, is a physiologic response to abdominal surgery, including the Whipple procedure.

[40] Though initially attempted as early as 1937 by Alexander Brunschwig,[38] the first successful pylorus-sparing pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed in 1976 by William Traverso and Longmire.