Panoramic painting

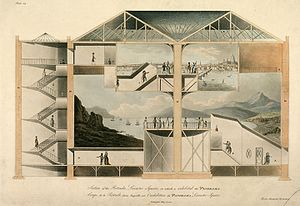

Panoramic paintings are massive artworks that reveal a wide, all-encompassing view of a particular subject, often a landscape, military battle, or historical event.

Typically shown in rotundas for viewing, panoramas were meant to be so lifelike they confused the spectator between what was real and what was image.

[2] Barker's vision was to capture the magnificence of a scene from every angle so as to immerse the spectator completely, and in so doing, blur the line where art stopped and reality began.

Viewers flocked to pay a stiff 3 shillings to stand on a central platform under a skylight, which offered an even lighting, and get an experience that was "panoramic" (an adjective that didn't appear in print until 1813).

[5] The main goal of the panorama was to immerse the audience to the point where they could not tell the difference between the canvas and reality, in other words, wholeness.

[4] Barker's accomplishment involved sophisticated manipulations of perspective not encountered in the panorama's predecessors, the wide-angle "prospect" of a city familiar since the 16th century, or Wenceslas Hollar's Long View of London from Bankside, etched on several contiguous sheets.

[6] Props were also strategically positioned on the platform where the audience stood and two windows were laid into the roof to allow natural light to flood the canvases.

To accomplish this, patrons walked down a dark corridor and up a long flight of stairs where their minds were supposed to be refreshed for viewing the new scene.

These large fixed-circle panoramas declined in popularity in the latter third of the nineteenth century, though in the United States they experienced a partial revival; in this period, they were more commonly referred to as cycloramas.

[19] The diorama was invented in 1822 by Louis Daguerre and Charles-Marie Bouton, the latter a former student of the renowned French painter Jacques-Louis David.

[20] The images rotated in a 73 degree arc, focusing on two of the four scenes while the remaining two were prepared, which allowed the canvases to be refreshed throughout the course of the show.

[12][20] While topographical detail was crucial to panoramas, as evidenced by the teams of artists who worked on them, the effect of the illusion took precedence with the diorama.

First unveiled in 1809 in Edinburgh, Scotland, the moving panorama required a large canvas and two vertical rollers to be set up on a stage.

[26] Despite the success of the moving panorama, Barker's original vision maintained popularity through various artists, including Pierre Prévost, Charles Langlois and Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux among others.

[26] The panorama's rise in popularity was a result of its accessibility in that people did not need a certain level of education to enjoy the views it offered.

[27] While easy access was an attraction of the panorama, some people believed it was nothing more than a parlor trick bent on deceiving its public audience.

[6] A phenomenon resulting from immersion in a panorama, the locality paradox happened when people were unable to distinguish where they were: in the rotunda or at the scene they were seeing.

[6] The locality paradox refers to the phenomenon where spectators are so taken with the panorama they cannot distinguish where they are: Leicester Square or, for example, the Albion Mills.

[29] In their earliest forms, panoramas depicted topographical scenes and in so doing, made the sublime accessible to every person with 3 shillings in his or her pocket.

[32] Because of his argument in The Prelude, it is safe to assume Wordsworth saw a panorama at some point during his life, but it is unknown which one he saw; there is no substantial proof he ever went, other than his description in the poem.

[1] Despite the power it wielded, the panorama detached audiences from the scene they viewed, replacing reality and encouraging them to watch the world rather than experience it.

The oldest known surviving panorama (completed in 1814 by Marquard Wocher) is on display at Schadau Castle, depicting an average morning in the Swiss town of Thun.

A fifth panorama, also depicting the Battle of Gettysburg, was willed in 1996 to Wake Forest University in North Carolina; it is in poor condition and not on public display.

In the area of the moving panorama, there are somewhat more extant, though many are in poor repair and the conservation of such enormous paintings poses very expensive problems.

Painted in Nottingham, England around 1860 by John James Story (d. 1900), it depicts the life and career of the great Italian patriot, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882).

Numerous battles and other dramatic events in his life are depicted in 42 scenes, and the original narration written in ink survives.

[citation needed] The Arrival of the Hungarians, a vast cyclorama by Árpád Feszty et al., completed in 1894, is displayed at the Ópusztaszer National Heritage Park in Hungary.

[citation needed] The Cyclorama of Early Melbourne, by artist John Hennings in 1892, still survives albeit having suffered water damage during a fire.

It places the viewer on top of the partially constructed Scott's Church on Collins Street in the Melbourne CBD.

The museum has panorama paintings by Bruno Liljefors (assisted by Gustaf Fjæstad), Kjell Kolthoff and several hundred preserved animals in their natural habitats.