Moving panorama

This attraction was extremely popular amongst the middle and lower classes for the way it was able to offer the illusion of transport for the viewer to a completely different location that they had most likely never seen.

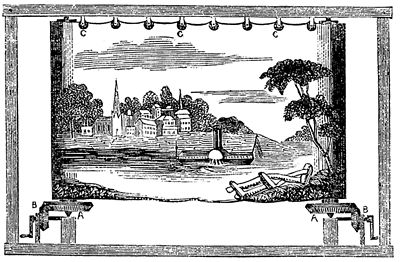

Moving panoramas were achieved by taking the long, continuous painted canvas scene and rolling each end around two large spool-type mechanisms that could be turned, causing the canvas to scroll across the back of a stage, often behind a stationary scenic piece or object like a boat, horse, or vehicle, to create the illusion of movement and travelling through space.

Unlike panoramic painting, the moving panorama almost always had a narrator, styled as its "Delineator" or "Professor", who described the scenes as they passed and added to the drama of the events depicted.

These moving panoramas were readily accepted in New York, where Americans loved the melodramatic genre of plays, which made use of the newest technologies and relied on spectacle.

William Dunlap, America’s first theatre historian, professional playwright, and a painter himself, was commissioned by the Bowery Theatre in New York in 1827 to write, somewhat reluctantly, A Trip to Niagara: or Travellers in America: A Farce, a satirical social comedy, specifically for an already existing painting of a steamboat journey up the Hudson River to the base of Niagara Falls, named the “Eidophusikon.” The production was extremely popular, not for the play, but for the spectacular moving scenery.

Today, we have much more realistic computer technology to create this illusion of movement, but the image of a stationary object or actor in front of a changing background harkens back to the moving panorama scroll.

In Philadelphia in 1811 nearly 1,300 feet (400 m) of painted cloth were unwound to display the Federal Procession of 1788,[2] and George IV's coronation in London was treated as a "Grand Historical Peristrephic Panorama" by the Marshall brothers.

In the 1877 Bureau County, Illinois, Voter's and Tax Payers,[5] page 361, William Mercer's possessions include two religious themed panoramas.

In 2016, the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign unveiled a display of part of a rare moving panorama which portrays the Annunciation, in which the angel Gabriel tells the Virgin Mary that she will become the mother of Jesus.

[6] In the early nineteenth century, British traveling panorama shows had been operated by several firms, among them the Marshall brothers of Glasgow and J.B. Laidlaw.

However, it was not until the 1850s that a nearly year-round programme of such shows was offered by Moses Gompertz, who with his assistants the Poole brothers traveled the length and breadth of Britain.

One naval battle had them manoeuvring ships accompanied by gunshot noises, puffs of smoke and Rule Britannia with waves on a rippling cloth at the front of the stage.

In December 1912 the Pooles first presented their Loss of the Titanic in "eight tableaux", starting with "a splendid marine effect" of the ship gliding across the scene.

Christensen's "Mormon Panorama" survives at Brigham Young University's Museum of Art, where it has been the subject of several recent shows and lectures.

Painted in Nottingham, England around 1860 by John James Story (d. 1900), it depicts the life and career of the great Italian patriot, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882).

[16] Crankies are moving panoramas on a smaller scale, with a typical example being roughly twenty feet long by eighteen inches high.

In the form of crankies, the moving panorama has experienced a revival in the United States since the mid-2010s; one group using them in its performances is the American folk duo Anna & Elizabeth.