Paracas culture

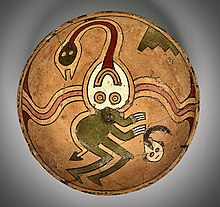

The associated ceramics include incised polychrome, "negative" resist decoration, and other wares of the Paracas tradition.

[3] The necropolis of Wari Kayan consisted of two clusters of hundreds of burials set closely together inside and around abandoned buildings on the steep north slope of Cerro Colorado.

Each burial consisted of a conical textile-wrapped bundle, most containing a seated individual facing north across the bay of Paracas, next to grave offerings such as ceramics, foodstuffs, baskets, and weapons.

Each body was bound with cord to hold it in a seated position, before being wrapped in many layers of intricate, ornate, and finely woven textiles.

[7] In the middle period (500–380 BCE) Chavín's influence on the Paracas culture dwindled and communities began to form their own unique identities.

[7] Relationships between these chiefdoms were not always peaceful, as evidence by violent battle wounds, trophy heads, and obsidian knives found at Paracas sites.

[8] The valley has extensive irrigation systems to increase agricultural production, a trait found throughout Paracas settlements and monumental sites.

[7] The site Cerro del Gentil in the Upper Chincha Valley dates to approximately 550–200 BCE and was used to host feasts for people throughout the Paracas sphere of influence.

[10][5] Nasca had shared religion with the Paracas, and continued the traditions of textile making, head-hunting, and warfare in early phases.

[11] In contrast, there are abundant Paracas remains in the Ica, Pisco, and Chincha valleys, as well as the Bahía de la Independencia.

[6][8] Radiocarbon dates show that the earliest accepted Topará site, Jahuay, was first occupied ~165 years after the closure of Cerro del Gentil.

[5][6] The Topará ceramic style is dominated by monochromatic designs, often decorated with an orange or neutral color clay slip.

[12] Nazca ceramics involved a focus on polychrome designs accomplished through the application of a slip consisting of clay and pigments obtained from minerals like manganese found in their environment.

[14] At Ocucaje, the early and middle phases of Paracas ceramics consisted of pigments (mostly red and green) that were rich in iron.

[18] Mummified human remains were found in a tomb in the Paracas peninsula of Peru, buried under layers of cloth textiles.

[10] The textiles would have required many hours of work as the plain wrappings were very large and the clothing was finely woven and embroidered.

[21] Once discovered, the Paracas Necropolis was looted heavily between the years 1931 and 1933, during the Great Depression, particularly in the Wari Kayan section.

[25][26] Paul also suggests that the detail and high quality of the textiles found in the mummy bundles show that these fabrics were used for important ceremonial purposes.

[27][26] Both native Andean cotton and the hair of camelids like the wild vicuña and domestic llama or alpaca come in many natural colors.

[28] Not only did these textiles show important symbols of the Paracas cosmology, it is thought that they were worn to establish gender, social standing, authority, and indicate the community in which one resided.

Red, green, gold and blue color was used to delineate nested animal figures, which emerge from the background with upturned mouths, while the stitching creates the negative space.

[32] The later used Block-color style embroidery was made with stem stitches outlining and solidly filling curvilinear figures in a large variety of vivid colors.

The therianthropomorphic figures are illustrated with great detail with systematically varied coloring.Like many ancient Andean societies, the Paracas culture participated in artificial cranial deformation.

[33] This association with sex has evidence in some Paracas ceramics, where men and women are depicted with distinctly Tabular Erect and Bilobate heads, respectively.

[33] The Paracas culture also shows evidence of the earliest trepanations in the Americas, using lithic scraping and drilling techniques to remove sections of the skull.

In addition, the Paracas geoglyphs show a significant difference in subjects and locations from the Nazca lines; many are constructed on a hillside rather than the desert valley floor.