Parallax

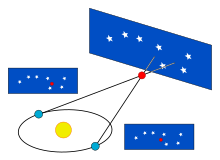

Here, the term parallax is the semi-angle of inclination between two sight-lines to the star, as observed when Earth is on opposite sides of the Sun in its orbit.

Parallax also affects optical instruments such as rifle scopes, binoculars, microscopes, and twin-lens reflex cameras that view objects from slightly different angles.

Many animals, along with humans, have two eyes with overlapping visual fields that use parallax to gain depth perception; this process is known as stereopsis.

This is the basis of stereopsis, the process by which the brain exploits the parallax due to the different views from the eye to gain depth perception and estimate distances to objects.

For example, pigeons (whose eyes do not have overlapping fields of view and thus cannot use stereopsis) bob their heads up and down to see depth.

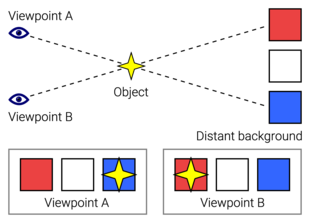

[4] The motion parallax is exploited also in wiggle stereoscopy, computer graphics that provide depth cues through viewpoint-shifting animation rather than through binocular vision.

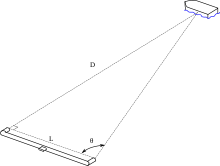

In astronomy, the triangle is extremely long and narrow, and by measuring both its shortest side length (the motion of the observer) and the small top angle (always less than 1 arcsecond,[5] leaving the other two close to 90 degrees), the length of the long sides (in practice considered to be equal) can be determined.

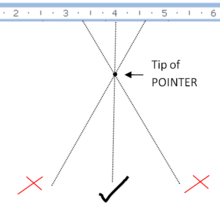

In surveying, the problem of resection explores angular measurements from a known baseline for determining an unknown point's coordinates.

As the Earth orbits the Sun, the position of a nearby star will appear to shift slightly against the more distant background.

Astronomers usually express distances in units of parsecs (parallax arcseconds); light-years are used in popular media.

The Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field Camera 3 has the potential to provide a precision of 20 to 40 microarcseconds, enabling reliable distance measurements up to 5,000 parsecs (16,000 ly) for small numbers of stars.

For a group of stars with the same spectral class and a similar magnitude range, a mean parallax can be derived from statistical analysis of the proper motions relative to their radial velocities.

However, secular parallax introduces a higher level of uncertainty because the relative velocity of observed stars is an additional unknown.

As the viewfinder is often found above the lens of the camera, photos with parallax error are often slightly lower than intended, the classic example being the image of a person with their head cropped off.

This problem is addressed in single-lens reflex cameras, in which the viewfinder sees through the same lens through which the photo is taken (with the aid of a movable mirror), thus avoiding parallax error.

[16] This parallax error is compensated for (when needed) via calculations that also take in other variables such as bullet drop, windage, and the distance at which the target is expected to be.

[citation needed] Scopes for guns with shorter practical ranges, such as airguns, rimfire rifles, shotguns, and muzzleloaders, will have parallax settings for shorter distances, commonly 50 m (55 yd) for rimfire scopes and 100 m (110 yd) for shotguns and muzzleloaders.

[22][23] Because of the positioning of field or naval artillery, each gun has a slightly different perspective of the target relative to the location of the fire-control system.

Several of Mark Renn's sculptural works play with parallax, appearing abstract until viewed from a specific angle.

One such sculpture is The Darwin Gate (pictured) in Shrewsbury, England, which from a certain angle appears to form a dome, according to Historic England, in "the form of a Saxon helmet with a Norman window... inspired by features of St Mary's Church which was attended by Charles Darwin as a boy".

Žižek notes The philosophical twist to be added (to parallax), of course, is that the observed distance is not simply "subjective", since the same object that exists "out there" is seen from two different stances or points of view.