Epistemology

Various epistemological disagreements have their roots in disputes about the nature and function of these concepts, like the controversies surrounding the definition of knowledge and the role of justification in it.

[43] In the second half of the 20th century, this view was put into doubt by a series of thought experiments that aimed to show that some justified true beliefs do not amount to knowledge.

[46] More specifically, this and similar counterexamples involve some form of epistemic luck, that is, a cognitive success that results from fortuitous circumstances rather than competence.

Often-discussed sources include perception, introspection, memory, reason, and testimony, but there is no universal agreement to what extent they all provide valid justification.

Epistemologists understand evidence primarily in terms of mental states, for example, as sensory impressions or as other propositions that a person knows.

But in a wider sense, it can also include physical objects, like bloodstains examined by forensic analysts or financial records studied by investigative journalists.

Some empiricists express this view by describing the mind as a blank slate that only develops ideas about the external world through the sense data it receives from the sensory organs.

It is commonly associated with the idea that the relevant factors are accessible, meaning that the individual can become aware of their reasons for holding a justified belief through introspection and reflection.

Instead, they focus on objective factors, like the quality of the person's eyesight, their ability to differentiate coffee from other beverages, and the circumstances under which they observed the cup.

One reason for adopting epistemic conservatism is that the cognitive resources of humans are limited, meaning that it is not feasible to constantly reexamine every belief.

[146] Other methods in contemporary epistemology aim to extract philosophical insights from ordinary language or look at the role of knowledge in making assertions and guiding actions.

[150] Some postmodern and feminist thinkers take a constructivist approach, arguing that the way people view the world is not a simple reflection of external reality but an invention or a social construction.

It understands knowledge as a holistic phenomenon that includes sensory, emotional, intuitive, and rational aspects and is not limited to the physical domain.

[154][n] Buddhist epistemology tends to focus on immediate experience, understood as the presentation of unique particulars without the involvement of secondary cognitive processes, like thought and desire.

Naturalistic epistemologists focus on empirical observation to formulate their theories and are often critical of approaches to epistemology that proceed by a priori reasoning.

[180][p] For example, Bayesian epistemology represents beliefs as degrees of certainty and uses probability theory to formally define norms of rationality governing how certain people should be.

[186][r] Epistemology and psychology were not defined as distinct fields until the 19th century; earlier investigations about knowledge often do not fit neatly into today's academic categories.

[190] Artificial intelligence relies on the insights of epistemology and cognitive science to implement concrete solutions to problems associated with knowledge representation and automatic reasoning.

Unlike many approaches in epistemology, the main focus of decision theory lies less in the theoretical and more in the practical side, exploring how beliefs are translated into action.

It studies the social and cultural circumstances that affect how knowledge is reproduced and changes, covering the role of institutions like university departments and scientific journals as well as face-to-face discussions and online communications.

It examines in what sociohistorical contexts knowledge emerges and the effects it has on people, for example, how socioeconomic conditions are related to the dominant ideology in a society.

In ancient Greek philosophy, Plato (427–347 BCE) studied what knowledge is, examining how it differs from true opinion by being based on good reasons.

[211][s] Plato's student Aristotle (384–322 BCE) was particularly interested in scientific knowledge, exploring the role of sensory experience and how to make inferences from general principles.

[212] Aristotle's ideas influenced discussions in the Hellenistic schools of philosophy, which began to arise in the 4th century BCE and included Epicureanism, Stoicism, and skepticism.

[217] The Upanishads, philosophical scriptures composed in ancient India between 700 and 300 BCE, examined how people acquire knowledge, including the role of introspection, comparison, and deduction.

[218] Ancient Chinese philosophers understood knowledge as an interconnected phenomenon fundamentally linked to ethical behavior and social involvement.

[224] Mozi (470–391 BCE) proposed a pragmatic approach to knowledge using historical records, sensory evidence, and practical outcomes to validate beliefs.

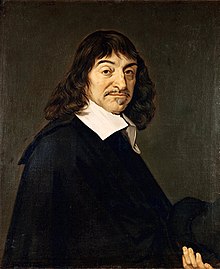

[238] Descartes, together with Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), belonged to the school of rationalism, which asserts that the mind possesses innate ideas independent of experience.

[243] John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), by contrast, defended a wide-sweeping form of empiricism and explained knowledge of general truths through inductive reasoning.

[252] Developed by philosophers such as Alvin Goldman (1938–2024), reliabilism emerged as one of the alternatives, asserting that knowledge requires reliable sources and shifting the focus away from justification.