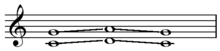

Consecutive fifths

However, parallel motion in perfect consonances (P1, P5, P8) is strictly forbidden in species counterpoint instruction (1725–present),[2] and during the common practice period, consecutive fifths were strongly discouraged.

This was primarily due to the notion of voice leading in tonal music, in which "one of the basic goals ... is to maintain the relative independence of the individual parts.

[citation needed] Whatever its origin, singing in parallel fifths became commonplace in early organum and conductus styles.

The early 15th-century composer Leonel Power likewise forbade the motion of "2 acordis perfite of one kynde, as 2 unisouns, 2 5ths, 2 8ths, 2 12ths, 2 15ths",[5] and it is with the transition to Renaissance-style counterpoint that the use of parallel perfect consonances was consistently avoided in practice.

[clarification needed] The interval may form part of a chord of any number of notes, and may be set well apart from the rest of the harmony, or finely interwoven in its midst.

88, "The trio is one of Haydn's finest pieces of rustic dance music, with hurdy-gurdy drones which shift in disregard of the rule forbidding consecutive fifths.

The disregard is justified by the fact that the essential objection to consecutive fifths is that they produce the effect of shifting hurdy-gurdy drones.

In the course of the 19th century consecutive fifths became more common, arising out of new textures and new conceptions of propriety in voice leading generally.

They even became a stylistic feature in the work of some composers, notably Chopin; and with the early 20th century and the breakdown of common-practice norms the prohibition became less and less relevant.

Therefore, parallel fourths above the bass are generally dismissed in voice leading as a series of consecutive unresolved dissonances.

Consecutive fifths are typically used to evoke the sound of music in medieval times or exotic places.

The use of parallel fifths (or fourths) to refer to the sound of traditional Chinese or other kinds of Eastern music was once commonplace in film scores and songs.

Since these passages are an obvious oversimplification and parody of the styles that they seek to evoke, this use of parallel fifths declined during the last half of the 20th century.

A positive organ having this configuration has been reconstructed recently by Van der Putten and is housed in Groningen, and is used in an attempt to rediscover performance practice of the time.

In Iceland, the traditional song style known as tvísöngur, "twin-singing", goes back to the Middle Ages and is still taught in schools today.

The background voice-leading of such progressions is oblique motion, with the consecutive fifths resulting from the ornamentation of the sustaining voice with a chromatic lower neighbor.

Another use of the term "Mozart fifths" results from the non-standard resolution of the German augmented sixth chord that Mozart used occasionally, such as in the retransition of the finale of the Jupiter Symphony (bars 221–222, second bassoon and basses), in the Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K. 448 (third movement, bars 276–277 (second piano)), and in the example at the right from Symphony No.

The Jupiter example is unique in that Mozart spells the fifth enharmonically (A♭/D♯ to G/D♮) as a result of the progression arising from a B-major harmony (presented as a dominant of e-minor).

"The parallel fifths [in the German sixth] arising from the natural progression to the dominant are always considered acceptable, except when occurring between soprano and bass.