Paramagnetism

It typically requires a sensitive analytical balance to detect the effect and modern measurements on paramagnetic materials are often conducted with a SQUID magnetometer.

Constituent atoms or molecules of paramagnetic materials have permanent magnetic moments (dipoles), even in the absence of an applied field.

In pure paramagnetism, the dipoles do not interact with one another and are randomly oriented in the absence of an external field due to thermal agitation, resulting in zero net magnetic moment.

The effect always competes with a diamagnetic response of opposite sign due to all the core electrons of the atoms.

However, in some cases a band structure can result in which there are two delocalized sub-bands with states of opposite spins that have different energies.

Generally, strong delocalization in a solid due to large overlap with neighboring wave functions means that there will be a large Fermi velocity; this means that the number of electrons in a band is less sensitive to shifts in that band's energy, implying a weak magnetism.

Moreover, the size of the magnetic moment on a lanthanide atom can be quite large as it can carry up to 7 unpaired electrons in the case of gadolinium(III) (hence its use in MRI).

Although there are usually energetic reasons why a molecular structure results such that it does not exhibit partly filled orbitals (i.e. unpaired spins), some non-closed shell moieties do occur in nature.

The unpaired spins reside in orbitals derived from oxygen p wave functions, but the overlap is limited to the one neighbor in the O2 molecules.

The paramagnetic response has then two possible quantum origins, either coming from permanent magnetic moments of the ions or from the spatial motion of the conduction electrons inside the material.

Curie's Law can be derived by considering a substance with noninteracting magnetic moments with angular momentum J.

is called the Bohr magneton and gJ is the Landé g-factor, which reduces to the free-electron g-factor, gS when J = S. (in this treatment, we assume that the x- and y-components of the magnetization, averaged over all molecules, cancel out because the field applied along the z-axis leave them randomly oriented.)

When orbital angular momentum contributions to the magnetic moment are small, as occurs for most organic radicals or for octahedral transition metal complexes with d3 or high-spin d5 configurations, the effective magnetic moment takes the form ( with g-factor ge = 2.0023... ≈ 2),

In doped semiconductors the ratio between Landau's and Pauli's susceptibilities changes as the effective mass of the charge carriers

Additionally, these formulas may break down for confined systems that differ from the bulk, like quantum dots, or for high fields, as demonstrated in the De Haas-Van Alphen effect.

Before Pauli's theory, the lack of a strong Curie paramagnetism in metals was an open problem as the leading Drude model could not account for this contribution without the use of quantum statistics.

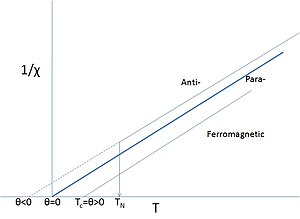

[5][6] Materials that are called "paramagnets" are most often those that exhibit, at least over an appreciable temperature range, magnetic susceptibilities that adhere to the Curie or Curie–Weiss laws.

In principle any system that contains atoms, ions, or molecules with unpaired spins can be called a paramagnet, but the interactions between them need to be carefully considered.

A gas of lithium atoms already possess two paired core electrons that produce a diamagnetic response of opposite sign.

Strictly speaking Li is a mixed system therefore, although admittedly the diamagnetic component is weak and often neglected.

The element hydrogen is virtually never called 'paramagnetic' because the monatomic gas is stable only at extremely high temperature; H atoms combine to form molecular H2 and in so doing, the magnetic moments are lost (quenched), because of the spins pair.

Although the electronic configuration of the individual atoms (and ions) of most elements contain unpaired spins, they are not necessarily paramagnetic, because at ambient temperature quenching is very much the rule rather than the exception.

[7] Thus, condensed phase paramagnets are only possible if the interactions of the spins that lead either to quenching or to ordering are kept at bay by structural isolation of the magnetic centers.

Salts of such elements often show paramagnetic behavior but at low enough temperatures the magnetic moments may order.

It is not uncommon to call such materials 'paramagnets', when referring to their paramagnetic behavior above their Curie or Néel-points, particularly if such temperatures are very low or have never been properly measured.

The sign of θ depends on whether ferro- or antiferromagnetic interactions dominate and it is seldom exactly zero, except in the dilute, isolated cases mentioned above.

Randomness of the structure also applies to the many metals that show a net paramagnetic response over a broad temperature range.

They are characterized by a strong ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic type of coupling into domains of a limited size that behave independently from one another.

The materials do show an ordering temperature above which the behavior reverts to ordinary paramagnetism (with interaction).

Ferrofluids are a good example, but the phenomenon can also occur inside solids, e.g., when dilute paramagnetic centers are introduced in a strong itinerant medium of ferromagnetic coupling such as when Fe is substituted in TlCu2Se2 or the alloy AuFe.