Paramylodon

Paramylodon is an extinct genus of ground sloth of the family Mylodontidae endemic to North America during the Pliocene through Pleistocene epochs, living from around ~4.9 Mya–12,000 years ago.

[2][3][4] In contrast, a study presented in 2019 by Luciano Varela and other involved scientists, which includes numerous fossil forms of the entire sloth suborder, partially challenged this.

Harlan commented two years later on the use of the name because, in his opinion, it did not describe any outstanding characteristic of the animal and could mean any extinct mammal because almost all of them had the posterior molars.

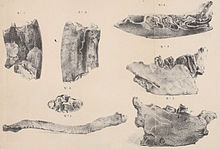

[12] In the same year, 1842, Owen presented a comprehensive description of a skeleton of a mylodont that came from the flood plains of the Río de la Plata north of Buenos Aires; he established for it the new species Mylodon robustus.

Only ten years later, Glover Morrill Allen created the species Mylodon garmani with the help of another partial skeleton from the Niobrara River in Nebraska,[17] but this is also considered a synonym of Paramylodon harlani.

The species was originally identified in 1925 by Lucas Kraglievich from a 39 cm long, nearly undamaged skull with mandible from Middle Pliocene strata east of Miramar in the Argentina Buenos Aires province.

However, whether this also applies to the North American finds from the Pliocene of Florida and Mexico, first listed under the same species name by Jesse S. Robertson in 1976, or these are closer to Paramylodon is currently unclear due to lack of comparative studies.

[16][10] Later, Chester Stock (1892-1950), based on his studies of the Rancho La Brea find material, pointed out that the feature of missing upper front teeth is highly variably developed in Mylodon harlani.

[25] Glossotherium had also originally been placed by Owen in his 1840 paper on Darwin's discoveries on the basis of a skull fragment from Arroyo Sarandí in southwestern present-day Uruguay, but only two years later he united it with Mylodon.

[26] With the subsequent full inclusion of Paramylodon into the genus, accomplished by Robert Hoffstetter in 1952, Glossotherium was among the few sloth forms that occurred in South and North America, but it also possessed high variability as a result.

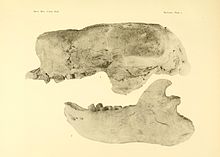

The skull, however, was shown to be altogether much narrower than in the comparably sized Glossotherium, the latter showing a dome-like bulge at the frontal line in side view, which did not occur in Paramylodon.

Several hundred osteoderms of Paramylodon are known from Rancho La Brea,[43][44][19] in addition, among others, also as a dense layer on a slab from Anza-Borrego State Park in California[45] and from Haile 15A, a fossil-rich limestone fissure in Florida.

These are distributed primarily in the southern and central areas of what is now the United States and northern Mexico, but also scatter in the western part of the continent as far south as the province of Alberta in Canada.

[49][10][50] One of the most significant sites of the period is the Leisey Shell pit in Hillsborough County in Florida, where several skulls and postcranial skeletal elements have been reported to be about 1.2 million years old.

[49][10][52] Among others, finds of a juvenile and an adult individual were recovered from Stevenson Bridge in stream deposits of Putah Creek in Yolo County of California, dating to the beginning of the Last Glacial Period.

In general, fossil remains of Paramylodon are very rare on the Colorado Plateau in the southwestern United States and additionally in northwestern Mexico, possibly related to the drier climate in this area at the time.

The ground sloth thus forms the fifth most abundant representative of mammals in the Diamond Valley Lake Local Fauna after bison, horses, the mastodon Mammut pacificus, and the camel Camelops.

[38] It is particularly striking that especially in the late Pleistocene at the time of the Last Glacial Period with its extremely pronounced climatic fluctuations, there is hardly any variation in size, as studies of the numerous finds from Rancho La Brea dating from 45,000 to 10,000 years Before Present indicate.

However, due to the body's center of gravity being shifted far to the rear, it was obviously also possible for them to change to a bipedal position, while being able to support themselves with the powerful - in contrast to today's tree sloths - very long tail.

This results in the pedolateral gait characteristic of numerous ground sloths, which required significant restructuring in the shape and bearing of the tarsal bones relative to each other, especially in the talus and calcaneus.

This is consistent with other mylodonts, but differs greatly from the closely related Scelidotheriidae, which had a highly arched foot with only the posterior end of the calcaneus touching the ground.

However, by the following year, Othniel Charles Marsh recognized a connection with extinct ground sloths and sought the originator of the stepping seals among the mylodonts, of which bone remains also exist from the same site.

Strikingly, thereby almost exclusively hind footprints have survived, which was initially also interpreted with a bipedal locomotion of the animals, analogous to corresponding trace fossils of Megatherium in South America.

The graminivorous diet was inferred based on the special tooth formation,[19] analyses of the masticatory apparatus of Paramylodon showed that food was predominantly crushed in forward, backward, and lateral chewing movements, which is also indicated by corresponding grinding marks.

The mandibular joint is broadly developed in Paramylodon and has an unspecialized surface, the associated glenoid fossa on the skull appears shallow, which is typical of herbivores with their rotary chewing movements.

Therefore, performing such methods requires excellent fossil preservation; in the case of Paramylodon, it was accomplished on the dentary of several teeth from the Upper Pleistocene site of Ingleside, Texas.

This is supported, for example, by the strong forelegs, which had a robust humerus widely projecting at the lower joint end, a short ulna with a long extended olecranon for massive forearm musculature, and somewhat flattened claws, making them very well suited for digging.

[10] The majority of the finds of Paramylodon are composed of single individuals, mass assemblages as for example in Rancho La Brea represent accumulations over several millennia.

[74][75] That early colonizers of North America interacted with, followed, as well as possibly hunted large ground sloths is indicated by footprints from White Sands National Monument in New Mexico.

During the period in question, in addition to Paramylodon, Nothrotheriops, a smaller ground sloth from the Nothrotheriidae group, and Megalonyx, a large genus of the Megalonychidae, occurred in the region.