Artiodactyl

CetartiodactylaMontgelard et al. 1997 Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla (/ˌɑːrtioʊˈdæktɪlə/ AR-tee-oh-DAK-tih-lə, from Ancient Greek ἄρτιος, ártios 'even' and δάκτυλος, dáktylos 'finger, toe').

Another difference between the two orders is that many artiodactyls (except for Suina) digest plant cellulose in one or more stomach chambers rather than in their intestine (as perissodactyls do).

Molecular biology, along with new fossil discoveries, has found that cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) fall within this taxonomic branch, being most closely related to hippopotamuses.

Some researchers use "even-toed ungulates" to exclude cetaceans and only include terrestrial artiodactyls, making the term paraphyletic in nature.

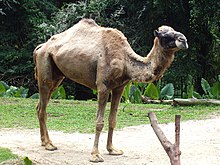

The roughly 270 land-based even-toed ungulate species include pigs, peccaries, hippopotamuses, antelopes, deer, giraffes, camels, llamas, alpacas, sheep, goats and cattle.

Since these findings almost simultaneously appeared in Europe, Asia, and North America, it is very difficult to accurately determine the origin of artiodactyls.

[4] The camels (Tylopoda) were, during large parts of the Cenozoic, limited to North America; early forms like Cainotheriidae occupied Europe.

In the late Eocene or the Oligocene, two families stayed in Eurasia and Africa; the peccaries, which became extinct in the Old World, exist today only in the Americas.

[citation needed] South America was settled by even-toed ungulates only in the Pliocene, after the land bridge at the Isthmus of Panama formed some three million years ago.

Comparison of even-toed ungulate and cetaceans genetic material has shown that the closest living relatives of whales and hippopotamuses is the paraphyletic group Artiodactyla.

The hippopotamids are descended from the anthracotheres, a family of semiaquatic and terrestrial artiodactyls that appeared in the late Eocene, and are thought to have resembled small- or narrow-headed hippos.

All other even-toed ungulates have molars with a selenodont construction (crescent-shaped cusps) and have the ability to ruminate, which requires regurgitating food and re-chewing it.

The most likely ancestors were long thought to be mesonychians—large, carnivorous animals from the early Cenozoic (Paleocene and Eocene), which had hooves instead of claws on their feet.

Their molars were adapted to a carnivorous diet, resembling the teeth in modern toothed whales, and, unlike other mammals, had a uniform construction.

[19] The suspected relations can be shown as follows:[16][20] Artiodactyla Mesonychia † Cetacea Molecular findings and morphological indications suggest that artiodactyls, as traditionally defined, are paraphyletic with respect to cetaceans.

Modern nomenclature divides Artiodactyla (or Cetartiodactyla) in four subordinate taxa: camelids (Tylopoda), pigs and peccaries (Suina), ruminants (Ruminantia), and hippos plus cetaceans (Whippomorpha).

Size varies considerably; the smallest member, the mouse deer, often reaches a body length of only 45 centimeters (18 in) and a weight of 1.5 kilograms (3.3 lb).

The Suina and hippopotamuses have a relatively large number of teeth (with some pigs having 44); their dentition is more adapted to a squeezing mastication, which is characteristic of omnivores.

Ruminants' mouths often have additional salivary glands, and the oral mucosa is often heavily calloused to avoid injury from hard plant parts and to allow easier transport of roughly chewed food.

[33] After the food is ingested, it is mixed with saliva in the rumen and reticulum and separates into layers of solid versus liquid material.

Cellulytic microbes (bacteria, protozoa, and fungi) produce cellulase, which is needed to break down the cellulose found in plant material.

Secretory glands in the skin are present in virtually all species and can be located in different places, such as in the eyes, behind the horns, the neck, or back, on the feet, or in the anal region.

Artiodactyls have a carotid rete heat exchange that enables them, unlike perissodactyls which lack one, to regulate their brain temperature independently of their bodies.

It has been argued that its presence explains the greater success of artiodactyls compared to perissodactyls in being able to adapt to diverse environments from the Arctic Circle to deserts and tropical savannahs.

Generally, even-toed ungulates tend to have long gestation periods, smaller litter sizes, and more highly developed newborns.

As with many other mammals, species in temperate or polar regions have a fixed mating season, while those in tropical areas breed year-round.

[citation needed] Artiodactyls have been hunted by primitive humans for various reasons: for meat or fur, as well as to use their bones and teeth as weapons or tools.

[35] Clear evidence exists of antelope being used for food 2 million years ago in the Olduvai Gorge, part of the Great Rift Valley.

Some species are synanthropic (such as the wild boar) and have spread into areas that they are not indigenous to, either having been brought in as farm animals or having run away as people's pets.

14 species are considered critically endangered, including the addax, the kouprey, the wild Bactrian camel, Przewalski's gazelle, the saiga, and the pygmy hog.