Parental investment

This theory has been influential in explaining sex differences in sexual selection and mate preferences, throughout the animal kingdom and in humans.

They increase their own reproductive success through feeding the offspring in relation to their own access to the female throughout the mating period, which is generally a good predictor of paternity.

For instance, ornate moth females receive a spermatophore containing nutrients, sperm and defensive toxins from the male during copulation.

Individuals are limited in the degree to which they can devote time and resources to producing and raising their young, and such expenditure may also be detrimental to their future condition, survival, and further reproductive output.

This conflict between survival, both emotional and physical, prompted a shift in cultural practices, thus resulting in new forms of investment from the mother towards the child.

[16] A range of behaviors fall under the term alloparental care, some of which are: carrying, feeding, watching over, protecting, and grooming.

However, the behavior can be explained evolutionarily as increasing indirect fitness, as the offspring is likely to be non-descendent kin, therefore carrying some of the genetics of the alloparent.

[better source needed] Trivers' theory does not account for women having short-term relationships such as one-night stands, and that not all men behave promiscuously.

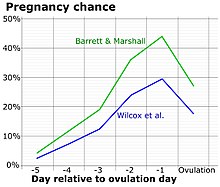

The fact that they are often the more investing sex leads to the second implication that evolution favors females who are more selective of their mates to ensure that intercourse would not result in unnecessary or wasteful costs.

The third implication is that because women invest more and are essential for the reproductive success of their offspring, they are a valuable resource for men; as a result, males often compete for sexual access to females.

[29] Parental investment theory is not only used to explain evolutionary phenomena and human behavior but describes recurrences in international politics as well.

Specifically, parental investment is referred to when describing competitive behaviors between states and determining aggressive nature of foreign policies.

The parental investment hypothesis states that the size of coalitions and the physical strengths of its male members determines whether its activities with its foreign neighbors are aggressive or amiable.

[30] According to Trivers, men have had relatively low parental investments, and were therefore forced into fiercer competitive situations over limited reproductive resources.

[30] One essential psychological developments involved decision-making of whether to take flight or actively engage in warfare with another rivalry group.

The male psychology conveyed in the ancient past has been passed on to modern times causing men to partly think and behave as they have during ancestral wars.

For example, the United States expected to win the Vietnam War due to its greater military capacity when compared to its enemies.

Yet victory, according to the traditional rule of greater coalition size, did not come about because the U.S. did not take enough consideration to other factors, such as the perseverance of the local population.

[30] The parental investment hypothesis contends that male physical strength of a coalition still determines the aggressiveness of modern conflicts between states.

While this idea may seem unreasonable upon considering that male physical strength is one of the least determining aspects of today's warfare, human psychology has nevertheless evolved to operate on this basis.

Moreover, although it may seem that mate seeking motivation is no longer a determinant, in modern wars sexuality, such as rape, is undeniably evident in conflicts even to this day.

In contrast, a female can have a much smaller number of offspring during her reproductive life, partly due to higher obligate parental investment.

An example of this is seen in crested auklets, where parents share equal responsibility in incubating their single egg and raising the chick.

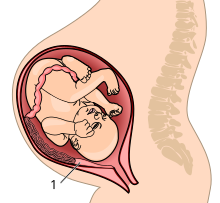

Human children are born unable to care for themselves and require additional parental investment post-birth in order to survive.

Relative to most other species, human mothers give more resources to their offspring at a higher risk to their own health, even before the child is born.

This is associated with the evolution of a slower life history, in which fewer, larger offspring are born after longer intervals, requiring increased parental investment.

The evolution of bipedalism altered the shape of the pelvis, and shrunk the birth canal at the same time brains were evolving to be larger.

The altered shape of the bipedal pelvis requires that babies leave the birth canal facing away from the mother, contrary to all other primate species.

It has been controversially claimed that humans have eusociality,[41] like ants and bees, in which there is relatively high parental investment, cooperative care of young, and division of labor.

[47][48][49][50] Father absence raises children's stress levels, which are linked to earlier onset of sexual activity and increased short-term mating orientation.