Paris in the 17th century

Paris became the home of the new Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, and of some of France's most famous writers, including Pierre Corneille, Jean Racine, La Fontaine and Moliere.

The Governor of Paris and the Provost of the merchants secretly joined Henry's side, and on March 2 the leader of the League, Charles de Mayenne, fled the city, followed by his Spanish soldiers.

Richelieu quickly showed his military skills and gift for political intrigue by defeating the Protestants at La Rochelle in 1628 and by executing or sending into exile several high-ranking nobles who challenged his authority.

During the first part of the regime of Louis XIII Paris prospered and expanded, but the beginning of French involvement in the Thirty Years' War against the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs in 1635 brought heavy new taxes and hardships.

An arranged a special mass at the Cathedral of Notre Dame, with the presence of the young King, to celebrate the victory, and brought soldiers into the city to line the street for the procession before the ceremony.

The Fronde rose again, this time led by two prominent nobles, the Prince de Condé, Gaston, Duke of Orléans, the Governor of Paris and the younger brother of the King, against Mazarin.

The leaders of the Parlement and the merchants of Paris, along with representatives of the clergy, assembled at the Hôtel de Ville and rejected Condé's proposal; they simply wanted the departure of Mazarin.

To make his intention clear Louis XIV organised a carrousel festival in the courtyard of the Tuileries in January 1661, in which he appeared, on horseback, in the costume of a Roman emperor, followed by the nobility of Paris.

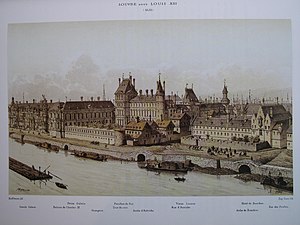

But another ambitious project, an exuberant design by Bernini for the eastern facade of the Louvre, was never built; it was replaced by a more severe and less expensive colonnade, whose construction proceeded very slowly due to a lack of funds.

On March 15, 1667, he named Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie to a new position, the Lieutenant General of Police, with the function of making the city work more efficiently, but also to suppress any opposition or criticism of the king.

One diarist, Robert Challes, wrote that, at the height of the famine, between fourteen and fifteen hundred people of both sexes and all ages were dying daily of hunger and disease at the Hôtel de Dieu hospital and on the streets outside.

Below the craftsmen and artisans was the largest class of Parisians; domestic servants, manual workers with no special qualifications, laborers, prostitutes, street sellers, rag-pickers, and a hundred other trades, with no certain income.

The status of bourgeois was granted to those Parisians who owned a house, paid taxes, had long been resident in Paris, and had an "honorable profession", which included magistrates; lawyers and those engaged in commerce, but excluded those whose business was providing food.

He wore an impressive ceremonial costume of a velour robe, silk habit and a crimson cloak, and was entitled to cover his horse and his dress his household servants in a special red livery.

Beneath the Provost and echevins there were numerous municipal officials, all selected from the bourgeoisie; two procureurs, three receveurs, a greffier, ten huissiers, a Master of Bridges, a Commissaire of the Quais, fourteen guardians of the city gates, and the governor of the clock tower.

He was responsible not only for the police, but also for supervising weights and measures, the cleaning and lighting of the streets, the supply of food to the markets, and the regulation of the corporations, all matters which previously had been overseen by the merchants of Paris.

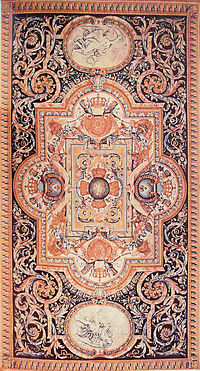

Henry IV and Louis XIII observed that wealthy Parisians were spending huge sums to import silks, tapestries, glassware leather goods and carpets from Flanders, Spain, Italy and Turkey.

Nearly all the clock and watchmakers were Protestants; when Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, most of the horlogers refused to renounce their faith and emigrated to Geneva, England and Holland, and France no longer dominated the industry.

In January 1662 the mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal, the inventor of one of the first calculating machines, proposed an even more original and rational means of transport; buying seats in carriages which traveled on a schedule on regular routes from one part of the city to another.

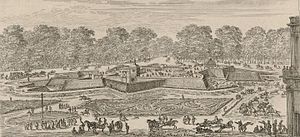

The return of Louis XIV and Queen Marie-Thérèse to Paris after his coronation in 1660 was celebrated by a grand event on a fairground at the gates of the city, where large thrones were constructed for the new monarchs.

Fireworks were first mentioned in Paris in 1581, and Henry IV had put on a small display at the Hôtel de Ville in 1598 after lighting the Fire of Saint Jean, but the first large show was given on April 12, 1612 following the Carrousel to mark the opening of the place Royale and the proposed marriage of Louis XIII with Anne of Austria.

Marie de' Medici, the widow of Henry IV, also was nostalgic for the gardens and promenades of Florence, particularly for the long tree-shaded alleys where the nobility could ride on foot, horseback and carriages, to see and be seen.

Pierre Corneille was from Normandy, Descartes from the Touraine, Jean Racine and La Fontaine from Champagne; they were all drawn to Paris by the publishing houses, theaters, and literary salons of the city.

This happened to one of the founding members of the Academy, Roger de Bussy-Rabutin, who in 1660 wrote a scandalous satirical novel about life at the court of Louis XIV, which was circulated privately to amuse his friends.

Another new company appeared in the tennis court of the Marais, at rue Vieille-du-Temple, staging works by another new playwright, Pierre Corneille, including his classical tragedies Le Cid, ''Horace, Cinna and Polyeute.

Chased from their home, the actors of Moliere moved to a different theater, called La Couteillle, on the modern rue Jacques-Callot, where they merged with their old rivals, the company of the Hôtel de Bourgogne.

The straight geometric lines of the buildings were covered with curved or triangular frontons, niches with statues or cariatides, cartouches, garlands of drapery, and cascades of fruit carved from stone.

[76] Civil architecture of the period was particularly characterized by red brick alternating with white stone around the windows and doors, and marking the different stories, and by a high roof of black slate.

Other painters who achieved fame in Paris early in the century were Claude Vignon, Nicolas Poussin, Philippe de Champagne, Simon Vouet, and Eustache Le Sueur.

The leading painters working in Paris and in Versailles during the reign of Louis XIV included Charles Le Brun, Nicolas de Largilliere, Pierre Mignard, Hyacinthe Rigaud and Antoine Watteau.