Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

J. Robert Oppenheimer, who had led Los Alamos National Laboratory during the Manhattan Project, exerted significant influence over the report, particularly in its recommendation of an international body that would control production of and research on the world's supply of uranium and thorium.

[24] Eisenhower, as president, first explicitly expressed interest in a comprehensive test ban that year, arguing before the National Security Council, "We could put [the Russians] on the spot if we accepted a moratorium ... Everybody seems to think that we're skunks, saber-rattlers and warmongers.

"[9] Then-Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had responded skeptically to the limited arms-control suggestion of Nehru, whose proposal for a test ban was discarded by the National Security Council for being "not practical.

[26] On the advice of Dulles, Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) chairman Lewis Strauss, and Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson, Eisenhower rejected the idea of considering a test ban outside general disarmament efforts.

[31] The proliferation of thermonuclear weapons coincided with a rise in public concern about nuclear fallout debris contaminating food sources, particularly the threat of high levels of strontium-90 in milk (see the Baby Tooth Survey).

[32] Lewis Strauss and Edward Teller, dubbed the "father of the hydrogen bomb,"[34] both sought to tamp down on these fears, arguing that fallout [at the dose levels of US exposure] were fairly harmless and that a test ban would enable the Soviet Union to surpass the US in nuclear capabilities.

In the mid-1950s, Soviet scientists began taking regular radiation readings near Leningrad, Moscow, and Odessa and collected data on the prevalence of strontium-90, which indicated that strontium-90 levels in western Russia approximately matched those in the eastern US.

Eisenhower, eager to mend ties with Britain following the Suez Crisis of 1956, was receptive to Macmillan's conditions, but the AEC and the congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy were firmly opposed.

[61] Following the Soviet declaration, Eisenhower called for an international meeting of experts to determine proper control and verification measures—an idea first proposed by British Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd.

[51][52] In the spring of 1958, chairman Killian and the PSAC staff (namely Hans Bethe and Isidor Isaac Rabi) undertook a review of US test-ban policy, determining that a successful system for detecting underground tests could be created.

[70] In a widely publicized and well-received communiqué dated 21 August 1958, the conference declared that it "reached the conclusion that it is technically feasible to set up ... a workable and effective control system for the detection of violations of a possible agreement on the worldwide cessation of nuclear weapons tests.

The US delegation was led by James Jeremiah Wadsworth, an envoy to the UN, the British by David Ormsby-Gore, the Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, and the Soviets by Semyon K. Tsarapkin, a disarmament expert with experience dating back to the 1946 Baruch Plan.

Eisenhower issued a statement blaming "the recent unwillingness of the politically guided Soviet experts to give serious scientific consideration to the effectiveness of seismic techniques for the detection of underground nuclear explosions."

Conversely, AEC chairman John A. McCone and Senator Clinton Presba Anderson, chair of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, argued that the Soviet system would be unable to prevent secret tests.

[90] Macmillan would later claim to President John F. Kennedy that the failure to achieve a test ban in 1960 "was all the fault of the American 'big hole' obsession and the consequent insistence on a wantonly large number of on-site inspections.

Second, there was the "finite containment" camp, populated by scientists like Hans Bethe, which was concerned by perceived Soviet aggression but still believed that a test ban would be workable with adequate verification measures.

[99] The historian Robert Divine also attributed the failure to achieve a deal to Eisenhower's "lack of leadership," evidenced by his inability to overcome paralyzing differences among US diplomats, military leaders, national security experts, and scientists on the subject.

Despite these findings, the Joint Chiefs of Staff dismissed Panofsky's report as "assertive, ambiguous, semiliterate, and generally unimpressive," reflecting the deep skepticism and tension within the U.S. government over Soviet activities and the broader test-ban negotiations.

[126] On 27 May 1963, 34 US Senators, led by Humphrey and Thomas J. Dodd, introduced a resolution calling for Kennedy to propose another partial ban to the Soviet Union involving national monitoring and no on-site inspections.

[143] In March 1963, Kennedy had also held a press conference in which he re-committed to negotiations with the Soviet Union as a means of preventing rapid nuclear proliferation, which he characterized as "the greatest possible danger and hazard.

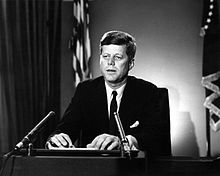

[145] On 10 June 1963, in an effort to reinvigorate and recontextualize a test ban, President Kennedy dedicated his commencement address at American University to "the most important topic on earth: world peace" and proceeded to make his case for the treaty.

"[124] Due to prior experience in arms control and his personal relationship with Khrushchev, former Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy was first considered the likely choice for chief US negotiator in Moscow, but his name was withdrawn after he turned out to be unavailable over the summer.

[148] "A test ban agreement combined with the signing of a non-aggression pact between the two groups of state will create a fresh international climate more favorable for a solution of the major problems of our time, including disarmament," Khrushchev said.

[148] Secret Sino-Soviet talks in July 1963 revealed further discord between the two communist powers, as the Soviet Union released a statement that it did not "share the views of the Chinese leadership about creating 'a thousand times higher civilization' on the corpses of hundreds of millions of people."

The following day, Kennedy delivered a 26-minute televised address on the agreement, declaring that since the invention of nuclear weapons, "all mankind has been struggling to escape from the darkening prospect of mass destruction on earth ...

"[159][160] In a speech in Moscow following the agreement, Khrushchev declared that the treaty would not end the arms race and by itself could not "avert the danger of war," and reiterated his proposal of a NATO-Warsaw Pact non-aggression accord.

Glenn T. Seaborg, the chairman of the AEC, also gave his support to the treaty in testimony, as did Harold Brown, the Department of Defense's lead scientist, and Norris Bradbury, the longtime director of the Los Alamos Laboratory.

Supporters of the deal mounted a significant pressure campaign, with active lobbying in favor by a range of civilian groups, including the United Automobile Workers/AFL–CIO, the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, Women Strike for Peace, and Methodist, Unitarian Universalist, and Reform Jewish organizations.

By the end of the 1970s, the US, the UK, and the Soviet Union reached an agreement on draft provisions that would prohibit all testing, temporarily ban peaceful nuclear explosions (PNEs), and establish a verification system that included on-site inspections.

Declassified documents also indicate that the US and the UK circumvented the prescribed verification system in 1964–65 by establishing a series of additional control posts in Australia, Fiji, Mauritius, Pakistan, and South Africa.